The Hausman Test and Weak Instruments"

advertisement

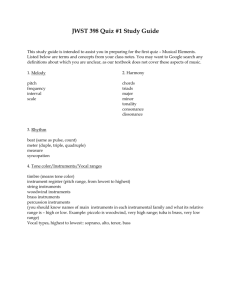

The Hausman Test and Weak Instruments Jinyong Hahn John Ham Hyungsik Rorger Moon UCLA USC USC May 25, 2007 Abstract We consider the following problem. There is a structural equation of interest that contains an explanatory variable that theory predicts is endogenous. There are one or more instrumental variables that credibly are exogenous with regard to this structural equation, but which have limited explanatory power for the endogenous variable. Further, there is one or more potentially ‘strong’ instrument, which has much more explanatory power but which may not be exogenous. Hausman (1978) provided a test for the exogeneity of the second instrument when none of the instruments are weak. Here we focus on how the standard Hausman test does in the presence of weak instruments using the Staiger-Stock asymptotics. We show that the standard version of the Hausman test is invalid in the weak instruments case. However, we provide a version of the Hausman test that is valid in the presence of weak IV. Further, for the case where the model is exactly identi…ed using only the weak IV, we show that one must make only a very simple modi…cation to the standard Hausman test. Our Monte Carlo experiments show that this procedure works relatively well in …nite samples. 1 Introduction Researchers often face the following problem. The have a structural equation of interest that contains an explanatory variable that theory predicts is endogenous. They want to obtain a con…dence interval for the estimated coe¢ cient on the structural parameter, or for a set of coe¢ cients from the structural equation. On the one hand they have one or more instrumental variables that credibly are exogenous with regard to this structural equation, but which have limited explanatory power for the endogenous variable. On the other hand they have one or more ‘strong instrument’, which has much more explanatory power but which may not be exogenous. The researcher can take one of several tacks. One obvious choice is to simply use the instruments that she is sure are endogenous to estimate the The second author acknowledges the support from National Science Foundation. Any opinions, …ndings, and conclusions or recommendations in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily re‡ect the views of the National Science Foundation. 1 structural equation by instrumental variable (IV) methods. However, given that the instruments are ‘weak’, the standard errors on the structural equation may be very large. Further, it may be the case that the standard asymptotic distribution for IV estimators is invalid because of the weak instrument problem. See, e.g., Bekker (1994), Staiger and Stock (1997), Kleibergen (2000), Donald and Newey (2001), Hahn and Hausman (2002), Moreira (2003), and Andrews, Moreira, and Stock (2004). The weak instruments problem has led to development to two strands of research, each of which is characterized by a di¤erent alternative asymptotic approximation. The …rst of these, which we will call the many-instrument asymptotics, emphasizes the …nite sample distortion which can be explained by the approximation where the number of instruments grows to in…nity as a function of the sample size. This literature often concludes that the IV estimators are still approximately normal, but that the asymptotic variance estimators need to address the …nite sample issue. See Bekker (1994), Donald and Newey (2001), Hahn and Hausman (2002), among others. Because the many-instrument asymptotics still produces a normal approximation for the estimators, the implication for practitioners is more or less a simple message that the standard error calculations need to be re…ned. On the other hand, there is a concern that the many-instrument asymptotics may not be relevant for situations where the degree of overidenti…cation is mild. Although the many-instrument asymptotics does not really require that the number of instruments is literally close to in…nity, it would be di¢ cult to justify it when the model is exactly identi…ed or mildly overidenti…ed. When the model is just or only mildly overidenti…ed, and the explanatory power of the instruments is small, the alternative approximation due to Staiger and Stock (1997) is appealing. This approximation is characterized by alternative asymptotics where the …rst stage coe¢ cient shrinks to zero as a function of the square root of the sample size. We will call this approximation the weak-instrument asymptotics. However, if the research attempts to use the weak instrument asymptotics, they face a practical problems that the con…dence interval for a parameter can be di¢ cult to construct or work with. Many empirical researchers are likely to …nd this prospect unattractive, especially since i) the variables known to be exogenous may not be weak instruments and ii) the ‘strong’instrument may be a valid instrument. One possibility for avoiding the procedure outlined above is to test whether the instruments known to be exogenous are indeed weak instruments. Unfortunately, there seems to be no consensus on what is a valid test for weak instruments. A second possibility is to ignore any endogeneity problems with the strong instrument, and simply base IV estimation on this variable. While this is probably to the most common path taken by empirical researchers, it leaves them open to the criticism that their estimates are inconsistent. Finally, there is a third possibility: if researchers are willing to live with the possibility of pretest bias, they could compare the IV estimates based on the strong and weak instruments using a Hausman test. If the test indicates that the use of the ‘strong’instrument is valid, then they do not need deal 2 with weak instrument issues. If the test indicates that the use of the strong instrument is invalid, then they know that they must address weak instrument issues. However, this raises the question of whether the Hausman test is valid in this context. In other words, since the standard Hausman test was developed under the conventional asymptotics, it may not be appropriate under weak-instrument asymptotics. In general the answer is that the standard version of the Hausman test is invalid in the weak instruments case. However, we provide a version of the Hausman test that is valid in the presence of weak IV. Further, for the case where the model is exactly identi…ed using only the weak IV, we show that one can adjust for weak instrument by making a very simple modi…cation to the standard Hausman test, albeit at the cost of some power unless the model is also exactly identi…ed under the strong IV. Thus our result is analogous to the Staiger and Stock (1997) result for the Hausman test of exogeneity of the (potentially endogenous) explanatory variable.1 Our Monte Carlo experiments show that our general procedure works relatively well in …nite samples. 2 Model and Assumptions In this note we consider an endogenous linear regression model, y1 = Y2 + " Y2 = Z + V; where " and V are mean zero unobserved error matrices, Y2 is a n are correlated with ", Z is an n K matrix of regressors that L matrix of instrumental variables (IV’s) with L K that are independent of V .2 Notation n denotes the sample size and all the asymptotic results of the paper assume that n ! 1: We assume that the IV’s consist of two components, Z = [W; S] ; where W; an n Lw , contains weak IV’s and S; n Ls matrix, contains strong but potentially invalid IV’s. More speci…cally, we assume that the coe¢ cient of the projection of Y2 on W shrinks to zero at the rate p1 , n while the coe¢ cient of projection of Y2 on S does not. For this purpose, we adopt the following parameterization: 1 C Y2 = W p + Se n s + V; In the context of comparing the weak IV against OLS, Staiger and Stock (1997) showed that a version of Hausman test as usually practiced has a correct asymptotic size, although they did observe that the test is not consistent. 2 We follow the standard approach, and assume that included exogenous variables are ‘partialled out’- see the online appendix for more details. 3 where Se is the residual when S is projected on W in the population S=W w e + S: ~ "; and V; respectively. We also denote y1i ; Y2i0 ; wi0 ; s0i ; s~0i ; "i ; and vi0 to be the ith row of y1 ; Y2 ; W; S; S; The main object of interest of the paper is to test for the validity of the strong IV’s in S. The hypotheses we are testing are H0 : E [si "i ] = 0 (or E [e si "i ] = 0) (1) H1 : E [si "i ] 6= 0 (or E [e si "i ] 6= 0). (2) Throughout this section, we will assume that the weak IV’s W are orthogonal to the regression error ", that is, E [wi "i ] = 0. If the exclusion restriction is violated, then it is only through the possible correlation between sei and "i . Let e We write that S. where v = [E (vi vi0 )] 1 s = [E (e si se0i )] " = Se s 1 E (e si "i ) denote the coe¢ cient of projection of " on +V v + e; (3) E (vi "i ) denotes the coe¢ cient of projection of "i on vi . We will assume that the ei is independent of sei and vi and has mean zero and variance 2I . e n Our null and alternative hypotheses can then be rewritten as 3 H0 : s =0 H1 : s 6= 0: Conventional Hausman Tests under Weak IV Asymptotics The basic idea of the Hausman test statistics for the null hypothesis (1) is based on the di¤erence of the following two estimators3 : b w b z = Y20 PW Y2 = Y20 PZ Y2 1 1 Y20 PW y1 Y20 PZ y1 : When the weakness of instruments is not an issue and the conventional asymptotic approximation is valid, then the instrument W is strong, b is an e¢ cient but non-robust estimator, while b is less z w e¢ cient but robust estimator. Then, the conventional Hausman test statistics measures the di¤erence b b with various weight matrices. We …rst consider three versions of the Hausman test: w z i 1 0h 1 1 2 2 0 0 b b b b ; H1 = b Y P Y b Y P Y 2 2 W Z w z w z ";w 2 ";z 2 i 1 0h 1 1 2 b b b b ; H2 = b";w Y20 PW Y2 Y20 PZ Y2 w z w z i 1 0h 1 1 b b ; H3 = b";z2 b w b z Y20 PW Y2 Y20 PZ Y2 w z 3 Given a matrix A; we use notation PA = A (A0 A) 1 A and MA = I 4 PA throughout the note. where b2";w = and 1 y1 n Y2 b w 0 Y2 b w y1 0 1 y1 Y2 b z y1 Y2 b z : n In Theorem 1 below, we adopt the alternative asymptotic approximation due to Staiger and Stock b2";z = 2 , K (1997) and show that, if H1 , H2 , or H3 is compared with then the asymptotic size of the test is di¤erent from the nominal size. It is also shown that the H3 does not have such a problem in the special case where the weak instrument W exactly identi…es , i.e., when Lw = K. We then provide a form of the Hausman test which is valid even when the model is overidenti…ed with the weak instruments. Before presenting Theorem 1, we introduce the set of assumptions employed in the paper. We assume homoscedasticity of “errors”, as is common in the literature. The homoscedasticity assumption allows us to further assume (without too much loss of generality) that 1 e0 e 1 S S = sese + op (1) ; V 0 V = vv + op (1) ; n n 1 0 1 0 2 2 e e = e + op (1) ; Y2 Y2 = 22 + op (1) ; " + op (1) ; n n 1 0 ZZ = n 1 0 "" = n + op (1) ; zz and 1 0 1 1 1 Z V; Z 0 e; Se0 V; Se0 e = op (1) ; n n n n where zz We also assume that 2 e p1 vec W 0 S 6 n 6 p1 vec (W 0 V ) 4 n p1 W 0 e n We will de…ne 3 2 vec (Zwes ) = " 3 7 6 7 7 ) 6 vec (Zwv ) 7 5 4 5 Zwe 1+ 1 2 " 1=2 1 22 Dw Nw ws sw ss # N 0; diag (Zwes ; Zwv ; Zwe ) = ww 0 1=2 22 vv v ww C + Zwes : ww ; sese 1=2 1 22 Dw Nw ww ; vv 2 e 1 1=2 22 vv v ww C + Zwes 0 2 v " vv ww 1 22 and (Zwes ; Zwv ) = 1 ( e ( ww C + Zwes s s + Zwv )0 + Zwv )0 where Dw and Nw are de…ned in (4) later in Appendix. 1 ww 1 ww Zwv v : Under the above set of assumptions, it can be shown: 5 ( s + Zwv ) 1=2 ; vv v Theorem 1 Suppose that Z denotes a random vector of N (0; IK ) that is independent of Under the null hypothesis (1), (a) H1 ; H2 ) (b) H3 ) 2 e 2 " 2 e 2 " (Zwes ; Zwv ; Zwe ) 1 (Zwes ; Zwv ). ( (Zwes ; Zwv ) + Z)0 ( (Zwes ; Zwv ) + Z). ( (Zwes ; Zwv ) + Z)0 ( (Zwes ; Zwv ) + Z) : Suppose that Lw = K; that is, W exactly identi…es : Then, under the null hypothesis (1), (c) H1 ; H2 ) (Zwes ; Zwv ; Zwe ) (d) H3 ) Z 0 Z 1 2 : K Z 0 Z: Proof. In Appendix. Remark 1 See the online appendix (Our online appendix is available at http://www-rcf.usc.edu/~johnham/) for implementing H3 using STATA. From this appendix one sees that a test based on H3 is quite easy to construct in STATA or similar programs. 4 Modi…cation of the Hausman Test for General Case Theorem 1 suggests that the usual Hausman test may have a size problem, except when the weak instrument W exactly identi…es ; that is, Lw = K. In order to overcome this complication, we propose a modi…cation that does not rely on the model being exactly identi…ed using the weak instruments. Our modi…cation is based on the following observation. First, under the null (1), we should have E [wi "i ] = 0. Our second observation is that the probability limit of b z will be di¤erent from under h i the alternative, and therefore, E wi y1i Y2i0 plim b z 6= 0. These observations suggest that it is not unreasonable to base the speci…cation test on p1 W 0 n Y2 b z . With some algebra, it can be y1 shown that Lemma 1 Under the null (1) and conventional asymptotics, 1 p W 0 y1 n where is the probability limit of 1 n b and b = W 0W Y2 b z ) N 0; W 0 Y2 Y20 PZ Y2 2 " 1 ; Y20 W : Proof. In the online Appendix. Therefore, the test statistic is equal to where b = W 0 W H b2" = 1 y1 b2" (W 0 Y2 ) (Y20 PZ Y2 ) 1 Y2 b z 0 Wb 1 W 0 y1 Y2 b z (Y20 W ) and b2" denotes some consistent estimator for 2. " In light of Lemma 1, it is straightforward to conclude that the (conventional) asymptotic distribution of H b2" is 2 . Lw 6 It turns out that the statistic H b2" is numerically identical a version of Hausman test when the weak IV wi exactly identi…es parameter : Proposition 1 When Lw = K, H b2" = 1 b w b2" Proof. In the online Appendix. b z 0h Y20 PW Y2 1 1 Y20 PZ Y2 i 1 b b w z : >From Theorem 1, we can conclude that H b2" can be understood as a version of Hausman test in a special case where Lw = K. Depending on the estimator b2" used, the statistic H b2" can be understood to be an extension of H2 or H3 . We now investigate the asymptotic property of H b2" under the weak instrument asymptotics. For this purpose, we will assume that the estimator b2" is consistent under the null even when we adopt the weak IV asymptotics: Lemma 2 Suppose that b2" is consistent for Then H b2" ) 2 " under the null using weak instrument asymptotics. 2 . Lw Proof. In Appendix. Remark 2 In Lemma 2, we make the additional assumption that b2" is consistent for 2 " under the weak instrument asymptotics. The assumption is made for the purpose of isolating the properties of the “numerator”, which is inspired by the discussion in the previous section, where we have seen 2 -distribution. that the H2 failed to converge to a proper inconsistent for 2. " The reason was that the estimator b2";w is We discuss below how to obtain a consistent estimate of 2 " with weak IV. We now discuss the power property of H b2" under the weak instrument asymptotics. For this purpose, let 2 =( (Zwes ) = 1 s )0 vv ( s )+ 2 e: Also, de…ne 1=2 s( s ww (Zwe s ) ww C ) where = plim b z 0 s = 1 sese s 0 s denotes the asymptotic bias of b z under the alternative hypothesis. sese s Lemma 3 Under the alternative hypothesis (2), H b2" ) 2 2 ( (Zwes ) + Z)0 ( (Zwes ) + Z) ; where Z denotes a random vector of N (0; ILw ) that is independent of limit of b2" under the alternative. 7 (Zwes ), and 2 is the probability Proof. In Appendix. Lemmas 2 and 3 imply that it is important to choose b2" such that it is consistent for the null, and consistent for under the alternative is 2 2 2 " under under the alternative. It can be shows that the probability limit of b2";z =( s s )0 sese ( s s )+ 2 .4 2= 2 Therefore, 1 if we use b2";z , which implies that the asymptotic distribution of H b2";z under the alternative is the mixture of 2 distribution ( (Zwes ) + Z)0 ( (Zwes ) + Z) multiplied by a constant less than or equal to 1. Therefore, it is not clear to us if the test H b2";z is asymptotically unbiased. We note that the potential problem can be avoided by developing an estimator of same limit as b2";z under the null, but converges to 2 2 " that has the under the alternative. This can be achieved by using an estimator computed by the following steps. Step 1: Using the IV estimator b z , we get the IV residual b "z = y1 Y2 b z : Step 2: Regress the IV residual b "z on Z = [S; W ] to get residual MZ b "z and de…ne e2";z = The proposed test statistic is then H4 = e";z2 y1 Y2 b z 0 h W W 0W By Proposition 1, H4 simpli…es to if Lw = K: H4 = e";z2 b w b z 0h 1 0 b " MZ b "z : n z W 0 Y2 Y20 PW Y2 Y20 PZ Y2 1 1 Y20 PZ Y2 Y20 W 1 i i 1 1 b W 0 y1 w b Y2 b z : z Remark 3 See the online appendix for implementing H4 using STATA. From this appendix one sees that a test based on H4 is quite easy to construct in STATA or similar programs. The preceding discussion leads to the following result: Theorem 2 (a) Under the null hypothesis, H4 ) 2 Lw : (b) Under the alternative hypothesis, H4 ) ( (Zwes ) + Z)0 ( (Zwes ) + Z) ; where Z 4 N (0; ILw ) and independent of See Lemma 6 in the appendix. (Zw1 se). 8 Theorem 2 shows that the limit distribution of H4 under the alternative is a mixture of a noncen- tral chi-square distribution with d.f. Lw = dim (wi ) and noncentrality parameter Therefore, the H4 is an asymptotically unbiased test. (Zw1 se)0 (Zw1 se). Although it is generally preferable to use the modi…ed estimator e2";z , there are two special cases where such modi…cation is not necessary. The …rst case is when 1=2 sese by the columns of s = s s (or s ). 1=2 sese s We then have = 1=2 sese s belongs to the space spanned 1=2 1 0 0 s ( s sese s ) s sese s , so that sese . This coincidence depends on the alternative, which is not known to the practitioner, so it probably has little practical importance. The second case is of more practical signi…cance. Suppose that the model is exactly identi…ed by the strong instrument si , that is, Ls = K,5 and We then have s = s s is invertible. , and there is no need for the second step modi…cation above. We believe that the second case is empirically more relevant than the …rst case, because in many applications the endogenous regressor Y2i and the strong IV si are scalars. 5 Monte Carlo Simulations The data generating process used in the Monte Carlo simulations is yi = Y2i + s0i Y2i = wi0 where (wi0 ; s0i ) iid simulations. The and s + s0i " + "i s 1 + vi ; #! i = 1; : : : ; n and Y2i is a scalar. We …xed = 1 in the 1 that we considered are proportional to vectors consisting of ones. They N (0; I) and ("i ; vi ) w iid w s N 0; are related to the (partial) …rst stage R2 by 2 Rw =1 0 s 0 w w s +1 + 0 s s +1 Rs2 = 1 ; 0 w 0 w w w + +1 0 s s +1 : 2 = 0:01; 0:02. We set We …xed Rs2 = 0:2 throughout the simulation, and we considered Rw under the null, and s s = 0 = ( s ; 0; : : : ; 0) under the alternative. All the simulation results are based on 5000 runs. We consider n = 100; 200; 500, 2 = 0:01; 0:02, and = 14 ; 12 ; 34 , Rw s = 1. The dimensions of wi and si are Lw = 1; 5 and Ls = 1; 2; 5; respectively. The nominal size of the test is 5%. (Additional cases are considered in the online Appendix.) Table A looks at the size of the test for H1 H4 when there is one weak IV and = 1 4 for di¤erent sample sizes and numbers of strong instruments. Thus we …rst consider the case where the model is exactly identi…ed using the weak instruments and the degree of endogeneity is relatively small. The …rst section of the table considers this speci…cation for the three di¤erent sample sizes and the two 5 Recall that Ls denotes the number of strong instruments 9 2 . Ideally each entry should be 0.05, so that we see that in each the size is much too small values of Rw for H1 and H2 but is dead on for H3 and H4 . The bottom two sections of Table 1 consider the case of two and …ve strong instruments respectively. Now the size of H3 is still equal to 0.05 except in two cases, while the H4 rises to 0.06 for most speci…cations. Table B looks at the size of the test for H1 H4 when there are …ve weak IV and = 34 ; i.e. a case where the model is overidenti…ed under the weak instruments and the degree of endogeneity is considerably higher. Now the size of each test is biased upwards - this is especially true for H1 and H2 : However, it is interesting to note that H4 substantially outperforms H3 , which is intuitively plausible since H4 was developed for the case where the model is potentially overidenti…ed using the weak instruments. Comparing results in Tables A and B does raise an interesting dilemma. On the one hand researchers can improve the size of the test by using only one of the weak IV’s when the model is overidenti…ed under the weak IV. On the other hand, since di¤erent researchers are likely di¤erent choices in terms of which weak IV to use, they will obtain di¤erent test results for identical models. Further, there is also the potential problem of researchers running all …ve regressions when there are …ve weak instruments and one endogenous variable, and choosing the results they like the best. In Table C we consider the power properties of H3 and H4 when there is one weak IV, …ve strong IV and s = (1; 0; : : : ; 0); i.e. only one of the strong instruments is invalid. Note that this is a conservative example in that it will be harder to reject the null when it is false than if all the strong IV were invalid. Given that we have weak instruments, it is unrealistic to expect the entries in Table C to be close to one. Not surprisingly, the power of each test rises with the sample size and the explanatory power of the weak instruments. It is also interesting to note that the power of H4 is often more than double that of H3 when n = 100, a little less than double that of H3 when n = 200, and about 50% greater than that of H3 when n = 500. Thus in terms of power, H4 substantially out performs H3 for all sample sizes in our example. This is to be expected as the model is overidenti…ed under the strong IV, and H4 was developed with power considerations in mind.6 (Recall that there is no need to use the modi…ed version of e2";z when the model is exactly identi…ed under the strong instruments.) 6 Conclusion Hausman (1978) provides a test for whether an instrument(s) is valid given that the model is identi…ed by other instruments which can be treated as exogenous. However, researchers often face the problem that the instruments that are known to be exogenous are also weak. Using Staiger-Stock asymptotics, we show that the standard Hausman test for this case is not valid in the presence of weak instruments. We then provide a form of the Hausman test that is valid under weak instruments, and show in an online appendix that this test is easy for empirical researchers to implement in a program like STATA. 6 The corresponding power statistics for H4 when the model is overidenti…ed under the weak instruments are somewhat higher than those in Table C. 10 Our Monte Carlo results suggest that this general test performs well in …nite samples. Appendix A Preliminaries Proofs of following lemmas are given in a supplementary appendix, which is available upon request. Lemma 4 The " following hold both under the # null and under the alternative. (a) (b) (c) 1 0 nZ Z !p 1 0 n Z Y2 !p 1 0 n Y2 Z ww " 1 0 nZ Z 0 w ww w ww 0 # 0 w ww w + : sese s 1 1 0 n Z Y2 0 s !p : sese sese s : Lemma 5 The following hold under the null hypothesis in Section 3. p1 W 0 " ) Zwv v + Zwe : "n # " 1 ( Y20 PW Y2 ( ww C + Zwes s + Zwv )0 ww (b) ) Y20 PW " ( ww C + Zwes s + Zwv )0 (c) n1 Z 0 " !p 0: (a) (d) 1 0 n Y2 " !p (e) b z !p : (f ) b2";z !p (g) e2";z !p ww C 1 ww + Zwes (Zwv v s + Zwv ) + Zwe ) # : vv v : 2: " 2: " Lemma 6 The " following # hold under the alternative hypothesis in Section 3. 0 (a) n1 Z 0 " !p : (b) b z !p (c) (d) (e) B sese s + , where p1 W 0 (" Y2 n 2 e";z !p ( s b2";z !p ( s ) ) Zwes ( 0 ) s vv 0 ) 0 s =( ( s s sese ( s sese s ) s )+ s 1 ) 0 s ww C 2: e )+( sese s : s + Zw1 v ( )0 vv ( ) + Zwe : s )+ s 2: e Proof of Theorem 1 Part (a) Here we show only the limit of H1 : The limit of H2 can be derived by similar fashion and we omit the proof. By Lemma 5(b) we have " # " 1 ( Y20 PW Y2 ( ww C + Zwes s + Zwv )0 ww ) Y20 PW " ( ww C + Zwes s + Zwv )0 11 ww C 1 ww + Zwes (Zwv v s + Zwv ) + Zwe ) # def = " Dw Nw # : (4) >From this, we can deduce that b w ) Dw 1 Nw . Also, by Lemma 5(d), (e), and (f), and Lemma Y 0P Y 4(c), we have b z = + op (1), b2";z = 2" + op (1), n1 Y20 " = vv v + op (1), and 2 nZ 2 = Op (1). Therefore, we obtain b2";w 1 0 "" n = 0 2 " ) 2 " = 0 2 bw 2Nw Dw 1 vv v 1=2 1 22 Dw Nw + 1 0 Y " + bw n 2 0 + Nw Dw 1 1=2 22 1 0 Y Y2 n 2 0 22 Dw 0 1 b Nw vv v 1=2 1 22 Dw Nw w 1=2 22 vv v 0 0 v vv 1 22 vv v ; b b Now note that 1 = b w ( + op (1) = 2 b";w Y20 PW Y2 0 2 b";w Y20 PW Y2 b + op (1) b b w w w b 0 b H1 = 2 2 b";z2 Y20 PZ Y2 b";z2 Y20 PZ Y2 b";w Y20 PW Y2 b";w Y20 PW Y2 o 0n 1 2 b";w Y20 PW Y2 + op (1) b";z2 Y20 PZ Y2 b";z2 Y20 PZ Y2 z + op (1) 2 = b";w "0 PW Y2 Y20 PZ Y2 n b";z2 w 1 Y20 PW Y2 2 " H1 ) + 1=2 1 22 Dw Nw 1=2 22 2 b";w 1 Y20 PW Y2 n z ) Y20 PW " + op (1) Y20 PW Y2 n where the last equality follows from b";z2 Y20 PZ Y2 n w = op (1). We therefore obtain 0 vv v 1=2 1 22 Dw Nw 1=2 22 1 0 v vv v vv 1 22 vv v 0 Nw Dw 1 Nw : Let Z= 1 e Then, Z and ( ww C + Zwes s + Zwv )0 1 ww ( ww C + Zwes s + Zwv ) 1=2 ( ww C + Zwes s + Zwv )0 1 ww Zwe : N (0; IK ) and Z is independent of (Zwes ; Zwv ) : Recalling the de…nitions of (Zwes ; Zwv ; Zwe ) (Zwes ; Zwv ), the limit of H1 is presented as 2 e 2 " (Zwes ; Zwv ; Zwe ) 1 ( (Zwes ; Zwv ) + Z)0 ( (Zwes ; Zwv ) + Z) : Part (b) Notice that under the null hypothesis, by Lemma 5(f), b2";z !p arguments in the proof of Part (a), we can show that H3 = " = " ) = " 2 e 2 " 2 b w 0 2 "0 PW Y2 2 Nw Dw 1 Nw Y20 PW Y2 b w Y20 PW Y2 1 + op (1) Y20 PW " + op (1) 0 ( (Zwes ; Zwv ) + Z)0 ( (Zwes ; Zwv ) + Z) : 12 2. " Using similar Part (c) case, de…ne 0 When W exactly identi…es , Nw Dw 1 Nw = (Zwv 1 Z= 1=2 ww (Zwv v " + Zwe ) v 1 ww + Zwe ) (Zwv v + Zwe ). In this N (0; IK ) : Then, the limit distribution of H1 (and H2 ) is now (Zwes ; Zwv ; Zwe ) 1 Z 0 Z as required. Part (d) As in the proof of Part (c), de…ne 1 Z= 1=2 ww (Zwv v " Then, the limit distribution of H3 is then Z 0 Z C + Zwe ) N (0; IK ) : 2 . K Proof of Lemma 2 The result easily follows from the proof of Lemma 3 by noting that s = 0, = 0, and " = e under the null. D Proof of Lemma 3 We start with the analysis of Y2 b z N = y1 Note that 1 p W 0 y1 n Y2 b z 1 1 = p W 0 " p W 0 Y2 n n 0 Wb 1 0 Y Z n 2 1 Y2 b z W 0 y1 1 1 ZZ n 1 0 Z Y2 n ! 1 1 0 Y Z n 2 1 0 ZZ n 1 1 0 Z ": n Using Lemmas 4, 5, 6, we can write 1 p W 0 y1 n 1 p W 0 (" n ) Zwes ( s Y2 b z = Y2 ) + op (1) s ) ww C + Zwv ( s ) + Zwe (5) Because 1 0 Y PZ Y2 = Op (1) ; n 2 1 0 W Y2 = Op n we have 1 0 WW n 1 0 W Y2 n 1 0 Y PZ Y2 n 2 1 1 0 Y W n 2 1 p n = ww + op (1) under both the null and the alternative. We may therefore write that N = (Zwes ( (Zwes ( ) s s s s ww C ) ww C 13 + Zwv ( + Zwv ( ) + Zwe )0 s s 1 ww ) + Zwe ) + op (1) (6) Now let Z= 1 1=2 ww (Zwv (Zwes ) = 1 1=2 s( s ww (Zwe ( s ) + Zwe ) ; and Then, it is easy to notice that Z between Zwes and Zwv ( s s ) ww C N (0; IK ), and independent of ): (Zwes ) because of independence ) + Zwe . By writing N = 2 ( (Zwes ) + Z)0 ( (Zwes ) + Z) + op (1) (7) we obtain the desired conclusion. References [1] Andrews, Donald W.K., Marcelo Moreira, and James H. Stock (2004): “Optimal Two-Sided Invariant Similar Tests for Instrumental Variables Regression”, Econometrica, forthcoming. [2] Bekker, Paul A. (1994): “Alternative Approximations to the Distributions of Instrumental Variable Estimators”, Econometrica, 62, 657-681. [3] Donald, Stephen D. and Whitney K. Newey (2001): “Choosing the Number of Instruments”, Econometrica, 69, 1161-1191. [4] Hahn, Jinyong and Jerry A. Hausman (2002): “A New Speci…cation Test for the Validity of Instrumental Variables”, Econometrica, 70, 163-189. [5] Hausman, Jerry A. (1978): “Speci…cation Tests in Econometrics”, Econometrica, 46, 1251-1271. [6] Kleibergen, Frank (2000): “Pivotal Statistics for Testing Structural Parameters in Instrumental Variables Regression”, Econometrica, 70, 1781-1803. [7] Moreira, Marcelo (2003): “A Conditional Likelihood Ratio Test for Structural Models”, Econometrica, 71, 1027-1048. [8] Staiger, Douglas., and James H. Stock (1997): “IV Regression with Weak Instruments,” Econometrica, 65, 557-586. 14 Table A: Size of Test (γs=0), # weak IV = 1, ρ=.25 n 100 100 200 200 500 500 100 100 200 200 500 500 100 100 200 200 500 500 # strong IV 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 5 5 5 5 5 5 R2 H1 H2 H3 H4 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.00 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.00 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.00 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.00 0.00 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.06 0.06 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.06 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.05 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.05 0.05 * R2 is the partial R2 of the weak IV. Table B: Size of Test (γs=0), # weak IV = 5, ρ=.75 n 100 100 200 200 500 500 100 100 200 200 500 500 100 100 200 200 500 500 # strong IV 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 5 5 5 5 5 5 R2 H1 H2 H3 H4 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.36 0.32 0.37 0.31 0.27 0.20 0.34 0.31 0.34 0.28 0.27 0.20 0.25 0.22 0.29 0.22 0.25 0.18 0.32 0.28 0.34 0.27 0.26 0.18 0.30 0.26 0.30 0.24 0.26 0.18 0.22 0.19 0.26 0.20 0.24 0.16 0.22 0.19 0.21 0.17 0.15 0.11 0.22 0.19 0.18 0.14 0.15 0.10 0.18 0.14 0.17 0.12 0.14 0.09 0.11 0.11 0.09 0.09 0.07 0.07 0.11 0.11 0.08 0.08 0.06 0.06 0.12 0.12 0.09 0.09 0.07 0.07 * R2 is the partial R2 of the weak IV. Table C: Power of Test (γs=1), # weak IV = 1, # strong IV = 5 n R2 ρ H3 H4 100 100 100 100 100 100 200 200 200 200 200 200 500 500 500 500 500 500 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.25 0.5 0.75 0.25 0.5 0.75 0.25 0.5 0.75 0.25 0.5 0.75 0.25 0.5 0.75 0.25 0.5 0.75 0.11 0.12 0.15 0.15 0.19 0.24 0.15 0.18 0.23 0.24 0.30 0.38 0.31 0.38 0.48 0.53 0.63 0.74 0.23 0.28 0.38 0.30 0.36 0.49 0.28 0.36 0.51 0.40 0.51 0.66 0.47 0.59 0.76 0.70 0.80 0.91 * R2 is the partial R2 of the weak IV.