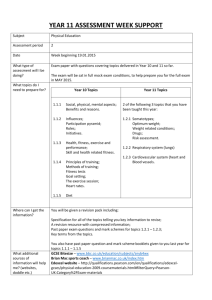

FITNESS ASSESSMENT AND PROGRAMME DESIGN FOR THE

advertisement