Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

www.elsevier.com/locate/dsw

Resource constraints and information systems implementation

in Singaporean small businesses

James Y.L. Thong ∗

Department of Information and Systems Management, School of Business and Management, Hong Kong University of Science

and Technology, Clear Water Bay, Kowloon, Hong Kong

Received 3 April 2000; accepted 5 July 2000

Abstract

While the information systems (IS) literature has identied potential factors of IS implementation success, none has

investigated the relative importance of these factors in the context of small businesses. Small businesses have very dierent

characteristics from large businesses; notably, small businesses suer from resource poverty. Without knowing the relative

importance of key factors, small businesses may be expending their limited resources and energy on less important factors which

have limited contribution to IS implementation success. This paper develops a resource-based model of IS implementation for

small businesses based on Welsh and White’s (Harv Bus Rev 59(4) (1981) 18–32) framework of resource constraints in small

businesses and Attewell’s (Organ Sci 3(1) (1992) 1–19) knowledge barrier theory. The model is then tested on a sample of

114 small businesses. The results show that small businesses with successful IS tend to have highly eective external experts,

adequate IS investment, high users’ IS knowledge, high user involvement, and high CEO support. External expertise is the

predominant key factor of IS implementation success in small businesses. ? 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: External expertise; Implementation; Information systems; Resource-based theory; Small business

1. Introduction

The computer-based information systems (IS) are a

major technological innovation during this century. The

benets of IS to large businesses are well-documented in

the popular press, trade magazines, and IS text books. At

the same time, the majority of IS research has concentrated

on IS implementation in large businesses. However, the literature has also argued that there is a relationship between

organizational size and IS implementation success (e.g.

[1– 4]). Due to the inherent dierences between small and

large businesses, research ndings based on large businesses

cannot be generalized to small businesses (e.g. [5 –8]). As

small businesses constitute over 90% of operating businesses in many countries, there is a great need for more rigorous research that is relevant to this important sector of the

economy [9].

∗

Tel.: +852-2358-7631; fax: +852-2358-2421.

E-mail address: jthong@ust.hk (J.Y.L. Thong).

Small businesses are under increasing pressure to employ

IS to maintain their competitive positions or simply to survive. At the same time, there are more barriers to IS implementation in small businesses than in large businesses due to

the high capital investment and skilled manpower involved

in implementing and operating IS. If the IS implementation is successful, potential benets to small businesses can

include increased sales, improved protability, increased

productivity, improved decision-making, and secured competitive positions (see [10 –14]). On the other hand, if the

IS implementation is unsuccessful, it will have severe repercussions on small businesses with their limited resources as

they can rarely rely on organizational slack to act as a buer

[15,16]. Hence, a key research question is identifying the

determinants of successful IS implementation in small businesses.

A review of the IS, small business, and management literature was conducted to assess the current state of research on

small businesses computerization. As we are examining IS

specically, it is highly relevant to review the IS literature.

0305-0483/01/$ - see front matter ? 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

PII: S 0 3 0 5 - 0 4 8 3 ( 0 0 ) 0 0 0 3 5 - 9

144

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

It is also relevant to include the small business literature as

we are studying the context of small businesses. Finally, the

management literature is included as it also publishes studies on the management of IS in small business. It should be

noted that we are interested in studies of factors that lead to

successful IS implementation rather than studies of factors

that lead to the decision to adopt IS or further IS adoption.

Adoption, implementation, and post-implementation (including further adoption) are three dierent stages in the

technology innovation cycle. The adoption stage is where a

decision is made about whether to adopt a new technology.

If the decision is to go ahead with adoption, the implementation stage involves implementing the technology in the

business. Once the technology has been implemented successfully, the post-implementation stage is concerned with

how much organizational learning takes place within the

business so as to facilitate further technology adoption

[17–19]. As the current study is concerned with the implementation stage, literature involving the second stage of the

technology innovation cycle will be most relevant.

Based on case studies and surveys, a number of potential

factors have been identied in the literature as critical to IS

implementation success in small businesses (e.g. [20 –28]).

However, there are limitations with the prior research. None

of the prior literature has investigated the relative importance of the identied factors of IS implementation success.

Without knowing the relative importance of these factors,

small businesses may be expending their limited resources

and energy on less important factors which have limited contribution to IS implementation success. Thus, there is a need

to identify the more important factors so that implications

and guidelines can be drawn for eective IS implementation

in small businesses. In addition, most of the prior studies

were carried out in the 1980s. Since then, computer hardware have become more powerful, software applications are

more sophisticated, and prices are increasingly more aordable even for small businesses. Some of the previously identied factors are no longer applicable in today’s business

environment (e.g. type of computer, interactive versus batch

systems, use of custom-developed applications). Thus, there

is also a need to reexamine the factors of IS implementation

success in small businesses in today’s context.

The prior literature also tends to use bivariate analysis,

specically correlation analysis. Bivariate analysis which

considers two variables at a time allows only a limited testing

of the research question. In comparison, multivariate analysis allows us to examine the eects of multiple independent

variables on a dependent variable simultaneously. Some researchers have even claimed that unless a problem is treated

as a multivariate problem, it is treated supercially. Further,

developments in structural equation modeling techniques, or

second-generation multivariate analysis, allow even stronger

tests to be brought to bear on the research question [29 –

31]. Thus, statistical techniques other than simple bivariate

analysis need to be utilized to provide a stronger test of the

research question. Finally, most prior studies used only one

key informant as representative of user evaluation of IS implementation success and sometimes this key informant may

not even be a user of the IS. The research design would be

more rigorous if multiple respondents were included [32].

The objective of this paper is to develop an updated IS

implementation model in small businesses. The model is

then tested on a survey sample of small businesses with

multiple respondents from each small business. The relative

importance of the key factors can then be examined using a

structural equation modeling technique [33].

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The following section describes the theoretical background for this

research. After that, we present the research model and develop the research propositions. We then describe the research methodology. This is followed by a presentation of

the data analysis results and discussion of the ndings. Finally, we conclude the paper with implications for practice

and research.

2. Theoretical background

Small businesses tend to have simple and highly centralized structures with the chief executive ocers (CEOs),

who are also the owners, making most of the critical decisions [34,35]. These CEOs have a great inuence on the

technology adoption decision [36,37]. Small businesses,

especially those with less than 100 employees, also tend to

employ generalists rather than specialists [38,39]. Operating

procedures are not written down or standardized. Other

distinctive characteristics include reliance on short-term

planning rather than long-term strategic plans, fewer bureaucratic procedures, less complex interpersonal and

political relations, and less organizational inertia [34,40].

Further, few small businesses use management techniques

such as nancial analysis, forecasting, and project management [6]. The decision-making process of small business

managers is more intuitive and less dependent on formal

decision models [41]. Due to their distinctive dierences

from large businesses, there is a need to examine small

businesses separately rather than as scale models of large

businesses (e.g. [5,8,42,43]).

The theoretical framework leading to the proposed IS implementation model for small businesses is based on the

resource-based theory of the rm [44 – 46]. This theory has

been hailed as a promising approach to the study of rms

[47– 49]. According to the resource-based theory, rms are

characterized as collections of resources or capabilities. A

rm’s resources may include both tangible and intangible

assets including capabilities, organizational processes, information, and knowledge, controlled by a rm that enable

the rm to conceive and implement strategies that improve

its eciency and eectiveness [50]. It emphasizes understanding the internal capabilities that enable rms to secure

competitive positions [47]. Further, the value of a resource

is likely to be partially contingent upon the presence of other

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

resources; i.e. a system of resources matter more than individual resources taken separately [51]. In this paper, the

resource-based theory of the rm is applied to the issue of

IS implementation success in small businesses.

Closely related to the concepts of resource-based theory is

Welsh and White’s [43] framework of resource constraints

in small businesses. According to them, the unique characteristics of small businesses are exemplied in the condition

known as resource poverty where small businesses operate under severe time constraints, nancial constraints, and

expertise constraints. Time constraints refer to the limited

amount of time available for activities beyond the normal

job responsibilities of individuals in the small businesses.

Due to their limited time, the CEOs and their employees

tend to have a short-range perspective with regard to IS

implementation and are not very involved in the IS implementation projects. If the CEOs and potential users do not

participate in the IS implementation, the quality of the IS will

suer. Financial constraints refer to the limited amount of

nance available for activities beyond the normal operations

of the small businesses. Due to their nancial constraints,

small businesses have to control their cash ows carefully

and do not have unlimited funds for their IS implementation

projects. They tend to choose the cheapest system which

may be inadequate for their purpose and underestimate the

amount of time and eort required for IS implementation

[52]. Expertise constraints refer to the limited amount of expertise within the small businesses to carry out activities beyond designated job responsibilities. They do not have the

necessary inhouse IS expertise or a formal IS department.

Small businesses tend to engage consultants and IT vendors

to develop and support their information systems. Due to

their lack of internal IS expertise, small businesses do not

have the capability to undertake their own IS implementation projects. In summary, resources such as time, nance,

and expertise, that are necessary for planning represent the

most critical diculties in small businesses [7]. Inadequate

resources spent on IS implementation increase the risk of IS

implementation failure.

While the resource-based theory emphasizes the importance of internal resources in a rm, external resources are

also important in the context of small businesses. Attewell’s

[53] technology diusion theory emphasizes the role of

external entities, such as consultants and IT vendors, as

knowledge providers in lowering the knowledge barrier or

knowledge deciency on the parts of potential IS adopters.

Small businesses tend to delay inhouse IS implementation

because they have insucient knowledge to implement IS

successfully. In response to this knowledge barrier, mediating entities come into existence which progressively lower

this barrier, and make it easier for small businesses to adopt

and implement IS without extensive inhouse expertise.

These mediating entities can capture economies of scale

in learning. After developing many systems, the IT vendor

would have learned from earlier attempts and developed a

relatively error-free system. Similarly, the consultant would

145

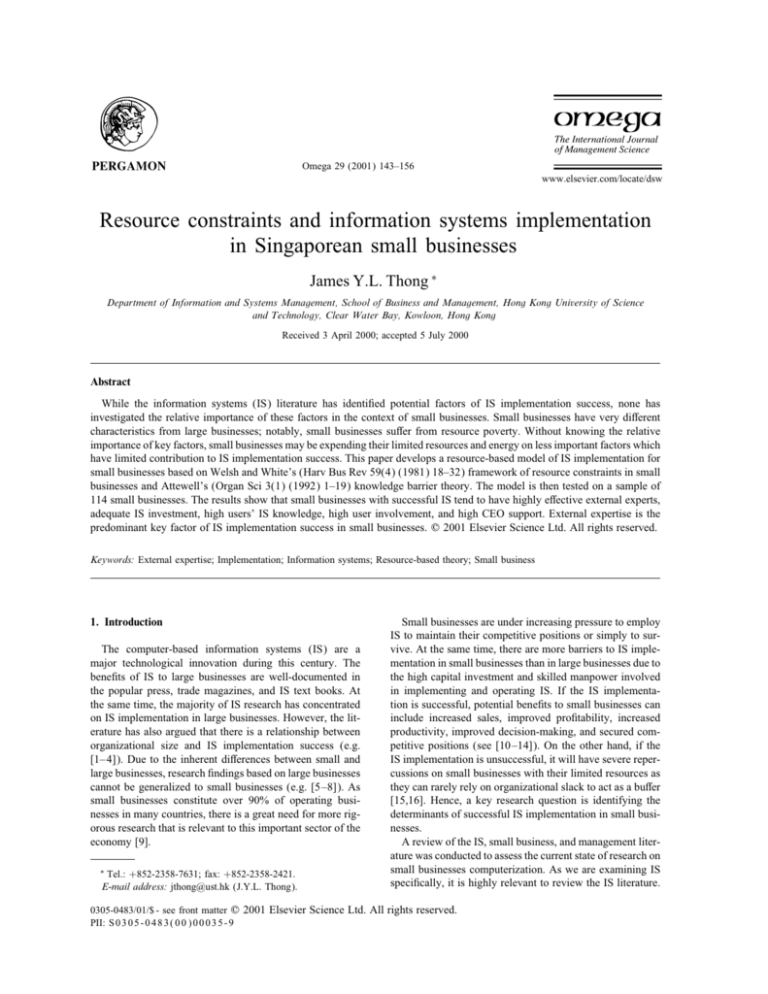

Fig. 1. Research model.

have acquired a wealth of experience in IS implementation.

Hence, external resources in the form of external experts

are also important to small businesses in implementing IS

successfully.

3. Research model

The research model is developed based on the prior theoretical background discussion (see Fig. 1). By adopting the

resource-based view of the rm and taking into account the

distinctive characteristics of small businesses, the IS implementation environment in a small business is conceptualized

in terms of three categories of resource constraints. The categories of resource constraints are time, nance, and expertise. While resources can also be viewed as facilitators, we

have adopted the view of constraints to be consistent with

Welsh and White’s [43] concept of resource poverty. Further, according to Attewell’s [53] knowledge barrier theory,

small businesses with their lack of internal IS expertise will

need to engage IS expertise from the external environment.

3.1. IS implementation success

Two popular constructs of IS implementation success

are user information satisfaction and organizational impact.

Based on a literature review of prior constructs of IS implementation success, DeLone and McLean [54] developed a

meta-model that included both user information satisfaction

and organizational impact as appropriate constructs of the

eectiveness of IS. These two constructs are elaborated on

below.

146

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

3.1.1. User information satisfaction

According to Seddon and Kiew [55], user information satisfaction may be considered the best “omnibus” construct of

IS implementation success. Other researchers [32,56] have

also argued that user information satisfaction provides the

most useful assessment of IS implementation success. User

information satisfaction may be dened as the extent to

which users believe the IS meet their information requirements [57]. If the IS meet the requirements of the users,

the users’ satisfaction with the IS will increase. Conversely,

if the IS do not provide the needed information, the users

will become dissatised. This denition of IS success is a

popular one in the IS literature. It can also be a meaningful surrogate for the critical but unquantiable result of the

IS, namely, changes in organizational eectiveness [57]. In

small business research, user information satisfaction has often been used as the dependent variable (e.g. [4,24 –26,58]).

Hence, user information satisfaction is used as a construct

of IS implementation success in this study.

3.1.2. Organizational impact

Organizational impact is dened as the impact of the IS

on the performance of the small business. IS implementation success only has meaning to the extent that the IS contribute to organizational eectiveness. In a small business,

the impact and value of the IS are likely to be achieved

through sta productivity, operations eciency, improvement in decision-making, increased sales revenue, increased

prot, and increased competitive advantage [59,60]. Further,

the eects of various factors on organizational impact of the

IS are mediated by user information satisfaction [54]. The

higher the level of user information satisfaction with the IS,

the greater will be the organizational impact on the business.

If the information needs of top management are met satisfactorily by the IS then their decision-making performance will

improve leading to increased positive organizational impact.

Hypothesis 1: Organizational impact is positively related

to the level of user information satisfaction.

3.2. Time constraint

3.2.1. CEO support

The CEO of a small business has limited time to spend

on IS implementation. But if the CEO can aord to be more

involved in the IS implementation project, the probability

of a successful implementation is much higher. The CEO

has the authority to inuence other members of the business and is more likely to succeed in overcoming organizational resistance to accept the IS [61]. Jarvenpaa and Ives

[62] noted that hands-on management in IS implementation

may be much more important in a small business where the

CEO commonly makes most key decisions and is perhaps

the only one who can harness IS to business objectives.

This is especially true in a small business where the CEO

is the person who understands the business best. A support-

ive CEO is also more likely to commit scarce resources and

adopt a longer-range perspective to the benets of IS implementation [63,64]. This is also believed to be the case in

small businesses [21,28,34]. Hence, it is hypothesized that

user information satisfaction is likely to be high when the

level of CEO support is high.

Hypothesis 2: User information satisfaction is positively

related to the level of CEO support.

3.2.2. User involvement

Employees in a small business tend to be generalists rather

than specialists in a certain eld [38,39]. They have multiple

job functions to perform within a limited time. Hence, if the

small business encourages the ultimate users to be involved

in the IS implementation by allowing them time-o from

their normal responsibilities, then the IS implementation is

more likely to be successful. Benets can include a better

t of the IS with user requirements, ease of operating the IS

due to learning experience during the design phase, feeling

of ownership, and reduced resistance to change [65 – 67].

Hence, it is hypothesized that user information satisfaction

is likely to be high when the level of user involvement is

high.

Hypothesis 3: User information satisfaction is positively

related to the level of user involvement.

3.2.3. IS planning

Similarly, if the small business can aord to spend more

time on IS planning, the chances of IS implementation success will be higher. The importance of IS planning in terms

of requirements analysis, system analysis and design, and

resource controls has been stated in the literature [68,69].

Ginzberg [64] identied the extent of project denition and

planning as a key recurrent issue in IS implementation success of large businesses. More eort spent on IS planning

can lead to better t of the business requirements with the

nal system. There is also some evidence of a positive relationship between user information satisfaction and the level

of IS planning in small businesses [25]. Hence, user information satisfaction is expected to be high when the level of

IS planning is high.

Hypothesis 4: User information satisfaction is positively

related to the level of IS planning.

3.3. Financial constraint

3.3.1. IS investment

Research has shown that sucient nancial resources increases the likelihood of IS implementation success [70,71].

As small businesses often lack nancial resources, insucient funds may be allocated for IS implementation.

Insucient nancial resources place constraints on the IS

implementation eort and often lead to selection of less

eective IS. Selection of such IS, although cheaper, will

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

result in false economy because the IS do not meet the

requirements of the business and will be inadequate in the

long run [52]. IS implementation involves capital investments and often has organization-wide implications. The

future of the business may be jeopardized by unsuccessful

investments in IS because a technical failure in the IS can

have a major negative impact on the business that is heavily

dependent on them. The setback has even greater ramication for a small business as it may even result in business

failure [72]. Hence, it is hypothesized that increased allocation for IS investment will increase the likelihood of IS

implementation success.

Hypothesis 5: User information satisfaction is positively

related to the level of IS investment.

3.4. Expertise constraint

3.4.1. Users’ IS knowledge

There is generally a lack of internal IS expertise in a small

business [22,39]. Employees are usually employed to work

on the daily operations of the business and not for their

ability to program or use software packages. Further, it is

dicult to recruit and retain IS professionals in a small business due to the tight labor market for IS professionals and

the absence of a career ladder for them in a small business.

However, if the employees have adequate IS knowledge,

they can contribute more eectively to the IS implementation through their involvement in the requirements and design phases. They will also have more realistic expectations

from the IS and be more comfortable participating in the IS

implementation process [66,73]. Insucient IS knowledge

has been found to lead to IS selection failure and failure

to use the IS [74]. Hence, it is hypothesized that a higher

level of IS knowledge is likely to increase IS implementation

success.

Hypothesis 6: User information satisfaction is positively

related to the level of users’ IS knowledge.

3.5. External expertise

Due to the lack of inhouse IS expertise, small businesses

are likely to be much more dependent on external expertise such as consultants and vendors [20,72]. According to

Attewell’s [53] theory, these external experts act as mediators to compensate for the lack of IS knowledge in the

small business and lower the IS knowledge barrier to successful IS implementation. The responsibilities of a consultant are to provide consultancy service specically to help

businesses implement eective IS. Consultancy service can

include performing information requirements analysis, recommending suitable computer hardware and software, and

managing the IS implementation [38]. The responsibilities

of a vendor generally include providing the computer hardware, software packages, technical support, and training

of users. It is also important to maintain a good working

147

relationship among the various parties (i.e. the CEO, users,

consultant, and vendor) in the IS implementation. In IS implementation of the small businesses, the vendor may also

play the role of a consultant, and thus performs additional

duties besides the usual responsibilities [58]. In view of the

possibility of the consultant being the vendor, we will treat

the responsibilities of the external experts as a combination

of the duties of the consultant and the vendor. In the research

model, external expertise is a second-order latent variable

of both types of external expertise. There is some prior

evidence to suggest positive correlations between user information satisfaction and external expertise [24,39]. Hence, it

is hypothesized that user information satisfaction is likely

to be high when the level of external expertise is high.

Hypothesis 7: User information satisfaction is positively

related to the eectiveness of external expertise.

4. Research methodology

4.1. Measurement of variables

The measures used in this study were developed through

an extensive literature review followed by iterative reviews

by both practitioners and experienced IS faculty. Further, the

measures had been used in prior studies and were found to

demonstrate adequate reliability and validity. The questionnaires containing the measures were also pilot-tested before

the main survey. Except for IS investment, the remaining

variables were measured as perceptual items on seven-point

Likert scales. Pre-tax prot and sales revenue were measured as seven-points Likert scales as small businesses are

reluctant to reveal actual revenue or prot. In order to secure their assistance in completing the survey questionnaire,

perceptual rather than objective measures were used. According to Dess and Robinson [75], subjective measures can

be appropriate surrogates for organizational performance.

Table 1 presents the measurement of the variables.

4.2. The sample

There is no generally accepted denition of a small business. Three commonly used criteria for dening a small

business are number of employees, annual sales, and xed

assets [76]. In this study, the criteria for dening a small

business were adopted from the Association of Small and

Medium Enterprises (ASME) in Singapore. A small business must satisfy at least two of the following criteria: (1)

number of employees should not exceed 100; (2) xed assets should not exceed US$7.2 million; and (3) annual sales

should not exceed US$9 million.

The names and addresses of small businesses that have

computerized were obtained from a database maintained

by the Singapore National Computer Board (NCB). The

148

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

Table 1

Measurement of variables

Variable

Measure

Source

User information satisfaction

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Currency of reports

Timeliness of reports

Reliability of reports

Relevancy of reports

Accuracy of reports

Completeness of reports

[57,85]

adapted

Organizational impact

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Pre-tax prot

Sales revenues

Sta productivity

Competitive advantage

Operating cost

Quality of decision-making

[59,60]

CEO support

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

CEO

CEO

CEO

CEO

CEO

attendance at project meetings

involvement in information requirements analysis

involvement in reviewing consultant’s recommendations

involvement in IS decision-making

involvement in monitoring project

[86]

User involvement

1.

2.

3.

4.

User

User

User

User

attendance at project meetings

involvement in information requirements analysis

involvement in reviewing consultant’s recommendations

involvement in IS decision-making

[86]

IS planning

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Financial resources planning

Human resources planning

Information requirements analysis

Implementation (software development, installation, and conversion)

Post-implementation (operation, maintenance, future needs)

IS investment

1. Investment in computer hardware and software

[4,70,87]

Users’ IS knowledge

1. Years of computer experience

2. Understanding of computers in comparison to persons in

your position at other small companies

3. Number of computer courses taken

[59]

Consultant eectiveness

1.

2.

3.

4.

Eectiveness in performing information requirements analysis

Eectiveness in recommending suitable computer solution

Eectiveness in managing implementation

Relationship with other parties in the project (CEO, Users, Vendor)

[58]

Vendor support

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Adequacy of technical support during IS implementation

Adequacy of technical support after IS implementation

Quality of technical support

Adequacy of training provided

Quality of training provided

Relationship with other parties in the project (CEO, Users, Consultant)

[58]

NCB conducts a national IT survey on a large cross-section

of business organizations every two years. Stratied random sampling was used to ensure that the sample was

representative of the national prole. Hence, our sample

was not a convenient sample per se. Nonprot businesses,

[86]

public-listed businesses, and wholly owned subsidiaries of

large businesses were excluded from the survey sample.

Three hundred and four small businesses fulll the ASME

criteria and were included in the survey sample. Two weeks

after the questionnaires were mailed, follow-up telephone

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

calls were made to nonresponding businesses to encourage

a higher response rate. One hundred and thirty small businesses responded, giving a response rate of 43%. Responses

from 16 businesses were excluded from the nal sample

because of incomplete data resulting in 114 usable sets of

questionnaires. In order to assess the possibility of nonresponse bias, we compared the responses of the early returns

with the late returns [77,78]. The rationale for this test is that

late respondents are likely to have similar characteristics

to nonrespondents. The MANOVA test did not detect any

signicant dierences in the research variables (Wilks’

= 0:958; F-sig: = 0:919), and hence nonresponse bias was

not a major concern.

4.3. Data collection

The study was conducted in two phases: a pilot study

and a questionnaire survey. Two questionnaires, the Project

Manager Questionnaire and the Computer User-Manager

Questionnaire, were designed for data collection. The rst

questionnaire was to be completed by the inhouse person

who was administratively responsible for IS implementation. It solicited data on the research variables and IS

characteristics. The second questionnaire was to be completed by senior managers who were users of the IS and the

computer-generated reports. It requested data on IS eectiveness and level of IS knowledge. Views from multiple

respondents were solicited to provide a more representative picture of the IS implementation success in the small

businesses.

In the pilot study phase, ve small businesses were randomly chosen from the small business database to pretest the

questionnaires. Five project managers and fteen managers

who used the businesses’ IS completed the questionnaires.

Interviews were conducted with these respondents in order

to determine whether there were problems with the questionnaires. Based on their feedback, some statements were

reworded and explanations were provided where necessary

to clarify the questions. Responses from these ve small

businesses were not included in the nal sample.

In the questionnaire survey phase, a package containing

four items was mailed to the CEO of each of the small business in the survey sample. The four items were: a cover

letter, one Project Manager Questionnaire, three Computer

User-Manager Questionnaires, and a prepaid envelope. The

cover letter requested the CEO to direct the relevant questionnaires to the manager in charge of the IS implementation project and three senior managers who used the IS.

The respondents were assured of the condentiality of their

responses. They could also return the completed questionnaires in individually sealed envelopes.

Interviews were also conducted with the project managers

and computer user-managers in 67 of the small businesses.

As far as possible, all managers who used the reports generated by the IS were included in the study. Responses from

the managers were not revealed to each other or the CEOs

149

of the small businesses. During the interviews, the respondents were asked to explain in greater detail their responses

to the questionnaires and to qualitatively relate their experience with the IS implementation projects. The interviews

helped us to interpret the questionnaire data through deeper

insights into IS implementation issues faced by these small

businesses. To check whether the CEOs in the noninterviewed businesses were biased in selecting managers who

were more satised with the IS, a MANOVA test was conducted on the variables between the 67 interviewed businesses and the 47 noninterviewed businesses. No signicant

dierence was found (Wilks’ = 0:905; F-sig: = 0:440).

Thus, there is no evidence of selection bias.

As the unit of analysis is at the organization level rather

than at the individual user level, the managers’ responses

were aggregated within each small business for purpose of

statistical analysis. In this study, respondents were members

of top management in the small businesses and were in a suitable position to view the success of the IS implementation.

Aggregation of individual responses into an organizational

response was done by averaging the scores by multiple respondents in the same business. The ANOVA tests revealed

signicantly greater variance for user information satisfaction and users’ IS knowledge between the small businesses

than within them, suggesting close agreement between respondents from the same business [4]. Hence, there was statistical support for aggregating the individual responses to

the organization level.

5. Findings

5.1. Sample characteristics

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the survey sample.

The responding small businesses were from the manufacturing, commerce, and service sectors. They all satised the

criteria of a small business as dened earlier. They employed

an average of 50 employees and the mean annual sales was

US$6 million. They had a mean of four years of computer

experience, and the majority had spent more than US$30,000

on their IS implementation. Their hardware platforms were

distributed evenly between microcomputers, microcomputers with local area networks, and minicomputers. Most of

the small businesses had implemented operational and management information systems applications such as accounting systems, inventory control, sales analysis, sales order

processing, and payroll. Finally, all of them had engaged

external experts to implement their information systems.

The eects of ve sample characteristics (number of

employees, annual sales, computer experience, type of

hardware, and business sector) on IS implementation success were examined. Correlation analysis showed that there

was no evidence of signicant correlations at the 10% level

between the IS eectiveness measures and the rst three

variables. The eects of type of hardware conguration and

150

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

Table 2

Characteristics of sample

5.2. Statistical analysis

Frequency (n = 114)a

Sector

Service

Commerce

Manufacturing

31

25

55

Number of employees

1–24

25 – 49

50 –74

75 –100

¿100

48

24

15

21

5

Annual sales (US$ million)

¡ $1:499

1.5 –$2.999

3.0 –$5.999

6.0 –$9.0

¿$9:0

28

27

14

14

25

Computer experience (yr)

0 –1

2–3

4 –5

6 –10

¿10

18

34

22

32

8

Computer expenditure (US$’000)

0 –30

31– 60

61–120

¿120

42

25

21

26

Hardware

Minicomputers and microcomputers

Microcomputers and LAN

Microcomputers only

43

34

33

Top 10 software applications

Accounts receivable

General ledger

Accounts payable

Inventory control

Sales analysis

Sales order processing

Payroll

Purchasing

Budgeting

Job Costing

96

90

87

74

50

47

40

29

24

23

a Figures

may not add up due to missing data.

business sector on the IS eectiveness measures were tested

using one-way ANOVAs. Similarly, there was no evidence

of signicant relationships (p ¿ 0:10). In summary, these

sample characteristics had no eect on IS implementation

success.

Partial least squares (PLS), a powerful second-generation

multivariate analysis technique or structural equation modeling technique, was used for hypotheses testing. PLS is

an approach to assess a causal model involving multiple

variables with multiple observed items by simultaneously

assessing both the structural model and the corresponding

measurement model in an optimal fashion [30,31]. It addresses both models at the same time; compared to factor

analysis which assesses the measurement model only and

path analysis which addresses the structural model alone.

Hence, PLS is superior to traditional regression and factor

analysis [31,79,80].

Fig. 1 presents the structural model in this study. The

structural model describes the relationships among the variables. Further, for each variable in the structural model, there

is a related measurement model (not shown in the gure),

which links each variable in the diagram with its respective

set of items. The items are listed in Table 1.

5.2.1. Testing the measurement model

Testing the measurement model involves examining internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant

validity. In PLS, internal consistency of the variables are

assessed with composite reliability. The advantage of

composite reliability over Cronbach’s alpha is that it is

not inuenced by the number of items in the scale [30].

Nunnally’s [81] guideline of 0.80 for assessing internal

consistency can be used to assess composite reliability.

Convergent validity is the degree to which two or more

items measuring the same variable agree [82]. In PLS, two

tests may be used to assess convergent validity. The rst test

is item reliability, which is measured by the factor loading

of the item on the variable. There is no generally accepted

level of what constitutes an acceptable factor loading in PLS

analysis. Fornell [79] recommended a minimum loading of

0.70 which suggests that the item explains almost 50 percent of the variance in the variable; while Falk and Miller

[83] recommended a loading should be at least 0.55 which

explains at least 30 percent of the variance in the variable.

Traditionally, researchers have used the 0.50 level [81]. The

second test is average variance extracted by each variable.

Fornell and Larcker’s [30] criterion that the average extracted variance should be 0.50 or more is usually used to

assess the average variance extracted coecients.

Table 3 presents the results of tests for internal consistency and convergent validity. The composite reliabilities

of all the variables were at least 0.80. All the factor loadings were greater than 0.55. While there were some loadings below the stricter limit of 0.70, the average variance

extracted of the variables were high. Using the average

variance extracted, which was a more conservative test of

convergent validity, all the variables had gures that exceeded 0.50. Hence, the variables in the measurement model

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

151

Table 3

Assessment of the measurement model in PLS

Variable

Mean

Standard

deviation

Factor

loading

User information satisfaction (1–7 scale)

Satisf1

Satisf2

Satisf3

Satisf4

Satisf5

Satisf6

5.55

5.55

5.52

5.73

5.73

5.38

0.95

0.87

0.99

0.83

0.93

0.82

0.82

0.81

0.86

0.85

0.86

0.82

Organizational impact (1–7 scale)

OrgImp1

OrgImp2

OrgImp3

OrgImp4

OrgImp5

OrgImp6

4.47

4.47

5.33

4.93

4.18

5.16

0.96

0.93

1.04

1.01

1.20

0.88

0.79

0.83

0.79

0.82

0.65

0.69

CEO support (1–7 scale)

CEO1

CEO2

CEO3

CEO4

CEO5

4.89

4.89

5.17

5.60

4.99

1.66

1.48

1.57

1.42

1.55

0.79

0.83

0.91

0.79

0.86

User involvement (1–7 scale)

Involve1

Involve2

Involve3

Involve4

5.33

5.34

4.71

5.13

1.43

1.36

1.49

1.39

0.96

0.92

0.58

0.66

IS planning (1–7 scale)

Plan1

Plan2

Plan3

Plan4

Plan5

4.67

4.51

5.09

4.97

4.84

1.36

1.25

1.24

1.16

1.12

0.65

0.72

0.83

0.76

0.68

IS investment (US$’000)

114

37

1.00

Users’ IS knowledge

CKnow1 (yr)

CKnow2 (1–7 scale)

CKnow3 (number)

5.19

4.48

2.99

3.42

1.14

3.99

0.71

0.96

0.56

Consultant eectiveness (1–7 scale)

Consult1

Consult2

Consult3

Consult4

5.03

4.53

4.76

5.13

1.13

1.28

1.24

1.28

0.81

0.78

0.88

0.88

Vendor support (1–7 scale)

Vendor1

Vendor2

Vendor3

Vendor4

Vendor5

Vendor6

4.76

4.48

4.67

4.29

4.28

4.79

1.46

1.71

1.51

1.60

1.60

1.31

0.87

0.83

0.86

0.90

0.90

0.84

Composite

reliability

Average variance

extracted

0.93

0.65

0.89

0.58

0.92

0.70

0.87

0.64

0.85

0.53

1.00

1.00

0.80

0.58

0.90

0.70

0.95

0.75

152

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

Table 4

Discriminant validity of measurement model in PLS

Variable

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

0.650a

0.200

0.037

0.063

0.056

0.020

0.066

0.062

0.191

0.580

0.031

0.108

0.122

0.002

0.029

0.042

0.020

0.700

0.178

0.147

0.000

0.008

0.061

0.015

0.640

0.073

0.000

0.025

0.072

0.022

0.530

0.000

0.050

0.154

0.070

1.000

0.068

0.044

0.002

0.580

0.056

0.011

0.700

0.304

0.750

User information satisfaction

Organizational impact

CEO support

User involvement

IS planning

IS investment

Users’ IS knowledge

Consultant eectiveness

Vendor support

a Diagonals represent the average variance extracted; other entries represent the shared variances. Shared variances = 0:000 means below

0.001.

demonstrated adequate internal consistency and convergent

validity.

Discriminant validity is the degree to which items differentiate between variables or measure dierent variables

[82]. Discriminant validity can be assessed by examining the

correlations between variables. Each item should correlate

more highly with other items of the same variable than with

items of other variables. To assess this, the squared correlation (shared variance) between two variables should be less

than the average variances extracted by the items measuring

the variables [30]. Table 4 presents the results of the test

for discriminant validity. In all cases, the shared variance

between two variables was less than the average variances

extracted by the items measuring the variables. Hence, the

requirement for the test of discriminant validity was satised, indicating that the measurement model discriminated

adequately between the variables.

5.2.2. Testing the structural model

Following conrmation of adequate psychometric properties in the measurement model, we proceeded to examine the

structural model. This evaluation consisted of an assessment

of the explanatory power of the independent variables, and

an examination of the size and signicance of the path coecients. Jackkning, a nonparametric technique, was used

to test the signicance of the paths. Fig. 2 presents the test

of the structural model. The model accounted for 26% of

the variance in user information satisfaction and 20% of the

variance in organizational impact. The percentage of variance explained was greater than 10%, implying a satisfactory and substantive model [83]. All the standardized path

coecients were signicant at the 5% level. However, a path

coecient may be statistically signicant but not meaningful. Pedhazur [84] recommended using the 0.05 level as the

threshold point. Following this guideline, hypotheses 1, 2, 3,

5, 6, and 7 were supported; only hypothesis 4 was not supported. The results show that user information satisfaction is

a key mediator between the antecedent factors and eventual

organizational impact on the small businesses. Among the

Fig. 2. Assessment of structural model.

key factors, external expertise is the variable most closely

related to user information satisfaction.

6. Discussion

The data analysis shows that external expertise is more

important than the other key factors in IS implementation

success of small businesses. In general, small businesses do

not have the resources to hire internal IS expertise and face

diculties in recruiting and retaining IS professionals. But

this lack of internal IS expertise may be compensated for

by engaging experienced external expertise, in the forms of

consultants and IT vendors, when undertaking IS implementation. Attewell [53] has argued that external institutions

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

play critical roles in lowering the knowledge barriers to IS

diusion, making it easier for businesses to adopt and use

the IS without extensive inhouse expertise. In the case of

small businesses, consultants and IT vendors perform the

role of external institutions that lower the knowledge barriers and make it easier for small businesses to implement IS

successfully. In a small business with its simple organizational structure and limited inter-personal and departmental

politics, IS implementation is essentially a technical matter. Under such circumstances, it is imperative to engage

external IS experts who are experienced, understand the requirements of small businesses, and able to maintain good

working relationships with all concerned parties. This was

borne in upon us in the interviews where the quality of the

external expertise was heavily stressed.

The level of users’ IS knowledge is another important

factor of IS implementation success. If the managers in the

small businesses have high levels of IS knowledge, the resulting IS are more likely to be successful. Potential IS users

should be sponsored by their companies to attend computer

courses to increase their appreciation of the IS implementation process and the potential benets of IS implementation.

With increased IS knowledge, these potential users will be

able to contribute more eectively to the IS implementation process and develop more realistic expectations of the

IS. Hence, taken together with the importance of external

IS expertise, a major nding of this study is that the lack

of IS expertise, whether internal or external, is the primary

barrier to successful IS implementation and is consistent

with Attewell’s [53] notion of “knowledge barriers” to successful IS implementation.

IS investment is the second most important determinant

of IS implementation success. This nding provides empirical support for Ein-Dor and Segev’s [2] hypothesis that

budgeting adequate nancial resources will increase the likelihood of IS implementation success. DeLone [1] has also

found that small businesses tend to spend proportionately

less of revenue on IS implementation than large businesses.

If small businesses could allocate sucient resources for

IS investment, not withstanding their tight cash ow, they

will be able to engage more experienced external experts

and contract for better IS that meet their objectives. If small

businesses decide to choose the lowest-cost external experts

and IS solutions, they may end up with IS solutions that do

not meet their business requirements. These scaled-down IS

solutions could ultimately even end up as white elephants,

as observed in some of the small businesses interviewed.

Thus, small businesses that are able to acquire the needed

capital for IS investment are more likely to secure successful IS. The interviews also revealed that small businesses

that lack nancial resources need to be proactive in securing

low-interest bank loans to nance their IS investment.

After technical expertise and nancial resource variables,

time-constrained variables are the next most important factors for IS implementation success. Due to time constraints

in small businesses, the CEOs and potential IS users could

153

not spend adequate time on IS planning and IS implementation. Among the three a priori time-constrained variables,

user involvement in IS implementation is the most important

for successful IS implementation. If the potential IS users

participate actively in the process of IS implementation, they

will be able to ensure that their suggestions and requirements are incorporated into the IS, feel a sense of ownership over the nal IS, and lower their resistance to adapt to

new work procedures. Adequate involvement of users can

compensate for the lower level of CEO involvement. While

the CEOs should be involved in key decisions aecting the

business and business processes, they need not be actively

involved throughout the IS implementation process. In fact,

given the heavy demand on the CEOs’ time and attention, it

is impractical to advise CEOs of small businesses to devote

a signicant amount of attention to the IS implementation

project. Surprisingly, the level of IS planning has no eect

on IS implementation success. A possible explanation that

emerged from the interviews is that most small businesses

do not consciously conduct IS planning. Beyond deciding

on how much to spend on IS, they are likely to depend on

the external experts in formulating other details of IS planning. In this study, IS planning is positively correlated with

the level of consultant eectiveness. Due to the recognized

importance of IS planning in prior IS implementation research in large businesses, further studies need to be conducted to determine the specic attributes of IS planning that

may have an eect on IS implementation success in small

businesses.

There are three limitations that should be noted in interpreting the ndings of this study. First, as this is a

cross-sectional study, causality of relationships cannot be

demonstrated completely. Further, feedback eects cannot

be investigated. Longitudinal studies are needed to conrm the direction of causality and test for feedback eects.

Second, signicant percentages of the IS implementation

success variances remain unexplained. More research on

this important topic is needed. Finally, in making generalization from the research sample, one has to take into consideration the context of Singapore, a newly industrialized

Asian country. The ndings may not be universally true,

but they are likely to be applicable to IS implementation

success in small businesses with similar cultural contexts

[39]. Findings from this study may also be applicable to

small businesses in developing countries that are interested

in adopting IS.

7. Conclusion

This paper has developed and tested a resource-based

model of IS implementation success in small businesses.

Based on Welsh and White’s [43] framework of resource

constraints in small businesses and Attewell’s [53] knowledge barrier theory, three types of resource constraints were

conceptualized: time constraint, nancial constraint, and

154

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

expertise constraint. Various key factors of IS implementation success were identied as technical expertise resource,

nancial resource, and time resource. The relative importance of these key factors of IS implementation success was

examined using a second generation multivariate technique

or structural equation modeling. The PLS analysis showed

good support for the IS implementation model with the

external technical expertise factor being the most important

followed by the nancial and time-constrained factors. User

information satisfaction was found to be a signicant mediator between these factors and the eventual organizational

impact of the IS.

The implication for small business management is that

to achieve a high level of IS implementation success,

they should direct their eorts at lowering three types

of resource barriers. The rst resource barrier is technical expertise constraints. Due to the lack of internal IS

expertise, small businesses need to engage experienced

consultants and IT vendors to undertake their IS implementation. They should also increase the level of IS knowledge

among potential IS users by sending employees for computer courses and training. The second resource barrier

is nancial constraints. Small businesses need to allocate sucient funds for their IS investment. While they

should not throw money at IS investment, which has not

been shown to be eective, they should also not opt for

the lowest-cost solutions which do not fulll their business requirements. Rather than purchase more expensive

custom-developed software, well-tested dedicated packages may well suit their needs. The third resource barrier

is time constraints. The busy CEO should ensure that

potential IS users are given time-o from their normal

duties to participate in the IS implementation process.

Potential IS users can provide useful inputs that will

lead to IS that better meet the requirements of the small

business.

The implication for research is that the resource-based

view of the rm and the resulting framework of resource

constraints are useful theories to ground future research on

IS implementation in small businesses. In this study, the

resource-based view was applied in conjunction with the

unique characteristic of small businesses and Attewell’s [53]

knowledge barrier theory to conceptualize the key factors of

IS implementation success in small businesses in terms of

three types of resource constraints. The proposed research

model for IS implementation in small businesses is one of

the few models that are guided by a strong theory. Future

research can extent the proposed model by examining other

key factors due to the three types of resource constraints

that may lead to successful IS implementation in small businesses. Further, the proposed model can be tested on samples of small businesses in other countries to determine its

generalizability. While small businesses everywhere suer

from resource constraints, do their contextual environments

have any eects? If found to be important, these factors will

need to be incorporated into the proposed model.

References

[1] DeLone WH. Firm size and the characteristics of computer

use. MIS Quarterly 1981;5(4):65–77.

[2] Ein-Dor P, Segev E. Organizational context and the success

of management information systems. Management Science

1978;24(10):1064–77.

[3] Iacovou CL, Benbasat I, Dexter AS. Electronic data

interchange and small organizations: adoption and impact of

technology. MIS Quarterly 1995;19(4):465–85.

[4] Raymond L. Organizational context and information systems

success: a contingency approach. Journal of Management

Information Systems 1990;6(4):5–20.

[5] Blau PM, Heydebrand WV, Stauer RW. The structure

of small bureaucracies. American Sociological Review

1966;31(2):179–91.

[6] Blili S, Raymond L. Information technology: threats and

opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises.

International

Journal

of

Information

Management

1993;13(6):439–48.

[7] Cohn T, Lindberg RA. How management is dierent in small

companies. New York: American Management Association,

1972.

[8] Dandridge TC. Children are not little ‘grown-ups’: small

business needs its own organizational theory. Journal of Small

Business Management 1979;17(2):53–7.

[9] Bannock G, Daly M. Small business statistics. London:

Chapman, 1994.

[10] Dwyer E. The personal computer in the small business:

ecient oce practice. Oxford: NCC Blackwell, 1990.

[11] Lincoln DJ, Warberg WB. The role of microcomputers

in small business marketing. Journal of Small Business

Management 1987;25(2):8–17.

[12] Massey Jr. TK. Computers in small business: a case

of under-utilization. American Journal of Small Business

1986;11(2):51–60.

[13] Meredith J. The strategic advantages of new manufacturing technologies for small rms. Strategic Management

Journal 1987;8(3):249–58.

[14] Poutsma E, Walravens A. Technology and small enterprises:

technology autonomy and industrial organization. Delft,

Holland: Delft University Press, 1989.

[15] Carter NM. Small rm adaptation: responses of physicians’

organizations to regulatory and competitive uncertainty.

Academy of Management Journal 1990;33(2):307–33.

[16] Gerwin D. A theory of innovation processes for

computer-aided manufacturing technology. IEEE Transactions

on Engineering Management 1988;35(2):90–100.

[17] Carayannis EG. The strategic management of technological

learning in project=program management. Technovation

1998;18(11):697–703.

[18] Lefebvre E, Lefebvre LA, Roy M-J. Technological penetration

and organizational learning in SMEs: the cumulative eect.

Technovation 1995;15(8):511–22.

[19] Lefebvre LA, Lefebvre E, Harvey J. Intangible assets as

determinants of advanced manufacturing technology adoption

in SMEs: toward an evolutionary model. IEEE Transactions

on Engineering Management 1996;43(3):307–22.

[20] Cragg PB, King M. Small-rm computing: motivators and

inhibitors. MIS Quarterly 1993;17(1):47–60.

[21] DeLone WH. Determinants of success for computer usage in

small business. MIS Quarterly 1988;12(1):51–61.

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

[22] Gable GG. Consultant engagement for computer system

selection: a pro-active client role in small businesses.

Information Management 1991;20(2):83–93.

[23] Gunasekaran A, Cecille P. Implementation of productivity

improvement strategies in a small company. Technovation

1998;18(5):311–20.

[24] Lees JD. Successful development of small business

information systems. Journal of Systems Management

1987;25(3):32–9.

[25] Montazemi AR. Factors aecting information satisfaction in

the context of the small business environment. MIS Quarterly

1988;12(2):239–56.

[26] Raymond L. Organizational characteristics and MIS success

in the context of small business. MIS Quarterly 1985;9(1):

37–52.

[27] Sohal AS. Introducing new technology into a small business:

a case study. Technovation 1999;19:187–93.

[28] Yap CS, Soh CPP, Raman KS. Information system success

factors in small business. Omega 1992;20(5=6):597–609.

[29] Bagozzi RP. Causal models in marketing. New York: Wiley,

1980.

[30] Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models

with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal

of Marketing Research 1981;18(1):39–50.

[31] Wold HA. Soft modeling: the basic design and some

extensions. In: Joreskog KG, Wold H, editors. Systems under

indirect observation. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1982.

[32] Hamilton S, Chervany NL. Evaluating information system

eectiveness part II: comparing evaluator viewpoints. MIS

Quarterly 1981;5(4):79–86.

[33] Chin WW, Gopal A. An examination of the relative

importance of four beliefs constructs on the GSS adoption

decision: a comparison of four methods. Proceedings of the

26th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

vol. IV, 1993. p. 548–57.

[34] Lefebvre E, Lefebvre LA. Firm innovativeness and CEO

characteristics in small manufacturing rms. Journal of

Engineering Technology Management 1992;9(3):243–77.

[35] Mintzberg H. The structuring of organizations. Englewood

Clis, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1979.

[36] Lefebvre LA, Harvey J, Lefebvre E. Technological experience

and the technology adoption decisions in small manufacturing

rms. R&D Management 1991;21(3):241–9.

[37] Lefebvre LA, Mason R, Lefebvre E. The inuence prism

in SMEs: the power of CEOs’ perceptions on technology

policy and its organizational impacts. Management Science

1997;43(6):856–78.

[38] Gable GG. A multidimensional model of client success

when engaging external consultants. Management Science

1996;42(8):1175–98.

[39] Thong JYL, Yap CS, Raman KS. Top management support,

external expertise, and information systems implementation

in small businesses. Information Systems Research 1996;

7(2):248–67.

[40] Harvey J, Lefebvre LA, Lefebvre E. Exploring the relationship

between productivity problems and technology adoption in

small manufacturing rms. IEEE Transactions on Engineering

Management 1992;39(4):352–8.

[41] Rice GH, Hamilton RE. Decision theory and the

small businessman. American Journal of Small Business

1979;4(1):1–9.

155

[42] D’Amboise G, Muldowney M. Management theory for

small business: attempts and requirements. Academy of

Management Review 1986;13(2):226–40.

[43] Welsh JA, White JF. A small business is not a little big

business. Harvard Business Review 1981;59(4):18–32.

[44] Penrose ET. The theory of the growth of the rm. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1959.

[45] Prahalad CK, Hamel G. The core competence of the

corporation. Harvard Business Review 1990;68(3):79–91.

[46] Wernerfelt B. A resource-based view of the rm. Strategic

Management Journal 1984;5(2):171–80.

[47] Conner KR. A historical comparison of resource-based theory

and ve schools of thought within industrial organization

economics: do we have a new theory of the rm? Journal of

Management 1991;17(1):121–54.

[48] Conner KR, Prahalad CK. A resource-based theory of the

rm: knowledge versus opportunism. Organization Science

1996;7(5):477–501.

[49] Montgomery CA. Of diamonds and rust: a new look at

resources. In: Montgomery CA, editor. Resource-based and

evolutionary theories of the rm: towards a synthesis. Norwell,

MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995.

[50] Barney J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage.

Journal of Management 1991;17(1):99–120.

[51] Foss NJ, Knudsen C, Montgomery CA. An exploration

of common ground: integrating evolutionary and strategic

theories of the rm. In: Montgomery CA, editor.

Resource-based and evolutionary theories of the rm: towards

a synthesis. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995.

[52] Yap CS. Issues in managing information technology. Journal

of the Operational Research Society 1989;40(7):649–58.

[53] Attewell P. Technology diusion and organizational learning:

the case of business computing. Organisation Science

1992;3(1):1–19.

[54] DeLone WH, McLean ER. Information system success:

the quest for the dependent variable. Information Systems

Research 1992;3(1):60–95.

[55] Seddon P, Kiew MY. A partial test and development of the

DeLone and McLean model of IS success. Proceedings of

the 15th International Conference on Information Systems,

Vancouver, BC, 1994. p. 99 –110.

[56] Powers RF, Dickson GW. MIS project management:

myths, opinions, and reality. California Management Review

1973;15(3):147–56.

[57] Ives B, Olson MH, Baroudi JJ. The measurement of

user information satisfaction. Communications of the ACM

1983;26(10):785–93.

[58] Thong JYL, Yap CS, Raman KS. Engagement of external

expertise in information systems implementation. Journal of

Management Information Systems 1994;11(2):209–31.

[59] DeLone WH. Determinants of success for small business

computer systems. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of

California, Los Angeles, 1983.

[60] Heikkila J, Saarinen T, Saaksjarvi M. Success of software

packages in small businesses: an exploratory study. European

Journal of Information Systems 1991;1(3):159–69.

[61] Markus ML. Power, politics, and MIS implementation.

Communications of the ACM 1983;26(6):430–44.

[62] Jarvenpaa SL, Ives B. Executive involvement and participation

in the management of information technology. MIS Quarterly

1991;15(2):205–27.

156

J.Y.L. Thong / Omega 29 (2001) 143–156

[63] Cerveny RP, Sanders GL. Implementation and structural

variables. Information Management 1986;11(4):191–8.

[64] Ginzberg MJ. Key recurrent issues in the MIS implementation

process. MIS Quarterly 1981;5(2):47–59.

[65] Barki H, Hartwick J. Rethinking the concept of user

involvement. MIS Quarterly 1989;13(1):53–63.

[66] Hirschheim RA. User experience with and assessment

of participative systems design. MIS Quarterly 1985;9(4):

295–304.

[67] Robey D, Farrow D. User involvement in information system

development: a conict model and empirical test. Management

Science 1982;28(1):73–85.

[68] Bowman B, Davis G, Wetherbe J. Three stages model of MIS

planning. Information Management 1983;6(1):11–25.

[69] King WR, Zmud RW. Managing information systems:

policy planning, strategic planning and operational planning.

Proceedings of the Second International Conference

on Information Systems, Cambridge, MA, 1981. pp.

299 –308.

[70] Ein-Dor P, Segev E, Blumenthal D, Millet I. Perceived

importance, investment and success of MIS, or the MIS ZOO.

Systems Objectives Solutions 1984;4:61–7.

[71] Tait P, Vessey I. The eect of user involvement on

system success: a contingency approach. MIS Quarterly

1988;12(1):91–108.

[72] Senn JA, Gibson VR. Risks of investment in microcomputers

for small business management. Journal of Small Business

Management 1981;19(3):24–32.

[73] Nelson RR, Cheney PH. Educating the CBIS user: a case

analysis. Data Base 1987;18:11–6.

[74] Neidleman LD. Computer usage by small and medium

sized European rms: an empirical study. Information &

Management 1979;2(2):67–77.

[75] Dess GG, Robinson RB. Measuring organizational

performance in the absence of objective measures: the case

[76]

[77]

[78]

[79]

[80]

[81]

[82]

[83]

[84]

[85]

[86]

[87]

of the privately-held rm and conglomerate business unit.

Strategic Management Journal 1984;5:265–73.

Ibrahim AB, Goodwin JR. Perceived causes of success

in small business. American Journal of Small Business

1986;11(2):41–50.

Armstrong JS, Overton TS. Estimating non-response bias in

mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research 1977;14(3):

396–402.

Gatignon H, Robertson TS. Technology diusion: an empirical

test of competitive eects. Journal of Marketing Research

1989;53(1):35–49.

Fornell C. A second generation of multivariate analysis,

methods: vol. 1. New York: Praeger, 1982.

Fornell C, Bookstein FL. Two structural equation models:

LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory.

Journal of Marketing Research 1982;19(4):440–52.

Nunnally JC. Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill,

1978.

Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experimentation: design and

analysis issues for eld settings. Boston: Houghton Miin

Co., 1979.

Falk RF, Miller NB. A primer for soft modeling. Akron, OH:

The University of Akron Press, 1992.

Pedhazur EJ. Multiple regression in behavioral research:

explanation and prediction, 2nd ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart

and Winston, 1982.

Raymond L. Validating and applying user satisfaction as a

measure of MIS success in small organizations. Information

Management 1987;12(4):173–9.

Yap CS, Thong JYL, Raman KS. Eect of government

incentives on computerization in small business. European

Journal of Information Systems 1994;3(3):191–206.

Srinivasan A, Kaiser KM. Relationships between selected

organizational factors and systems development. Communications of the ACM 1987;30(6):556–62.