SHA Cover40(1) - Society for Historical Archaeology

advertisement

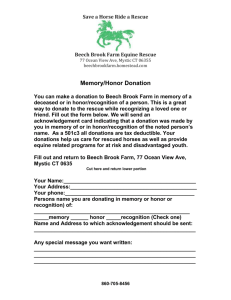

6 Robert W. Preucel Steven R. Pendery Envisioning Utopia: Transcendentalist and Fourierist Landscapes at Brook Farm, West Roxbury, Massachusetts ABSTRACT Brook Farm, Massachusetts, is perhaps the most famous of the 19th-century utopian communities in America. When it was founded in 1841, its guiding vision was provided by the distinctive New England philosophy known as Transcendentalism. Yet, only three years later, in 1844, it publicly embraced Fourierism and became known as the Brook Farm Phalanx. Archaeological work is providing new information on how these ideologies were inscribed in the landscape, showing that the architectural features built during the Transcendentalist period helped create certain habits of thought and action that actively resisted the complete transition from Transcendentalism to Fourierism. Introduction Social reform was one of the dominant themes in the United States in the first half of the 19th century (Guarneri 1991). During this period, social issues such as abolitionism, women’s rights, temperance, Grahamism, labor associations, education, and prison and asylum reform were being debated in almost every major city. While these reform movements did much to raise the visibility of specific causes, none of them developed a coherent vision of a new society. This task was left to the numerous utopian communities founded by the Shakers, Mormons, Oneida Perfectionists, and Harmonists, among others, that were springing up across the country. These communities were committed to changing society by implementing radical ideas about economic and social organization. One of the most famous of these utopian communities was Brook Farm, founded by George and Sophia Ripley. Indeed, it has sometimes been called a “literary utopia” due Historical Archaeology, 2006, 40(1):6–19. Permission to reprint required. to the scholarly and literary inclinations of its members. The most distinguished Brook Farm author is Nathaniel Hawthorne, the first treasurer of the Brook Farm Association. Hawthorne’s (1852) popular novel The Blithedale Romance memorialized daily life in the community during its Transcendental incarnation. George Ripley, the founder of the community, edited a popular series, entitled Specimens of Foreign Standard Literature, and translated leading German and French philosophers into English. In addition, Ripley was a regular contributor to The Dial, the Transcendentalist organ edited by Margaret Fuller. Upon its demise, Ripley and fellow Brook Farmers Charles Dana and John Dwight wrote for the Harbinger, a pro-Fourierist journal devoted to social reform and published for three years at Brook Farm. Largely because of this literary character, the amount of historical documentation and academic scholarship for Brook Farm is unusually rich. Letters and notes of individual members are preserved (Dwight 1928; Hawthorne 1932; Haraszti 1937), and reminiscences by former members and students have been published (Codman 1894; Sumner 1894; Russell 1900; Sears 1912). In addition, Brook Farm has been the subject of more than 200 scholarly articles, books, and dissertations (Myerson 1978), and it figures prominently in studies of New England literary culture (Delano 1983; Buell 1986). Given this scholarship, one might reasonably ask what can historical archaeology contribute to knowledge of this well-known community? There are two standard answers to this question. The first is that archaeology can be combined with historical documents to create more broadly based interpretations of past social contexts. This is particularly important given that written documents can provide only partial accounts reflecting the parochial interests of specific authors. The second is that archaeology can help recover information on individuals and social groups that are not usually chronicled in the documentary record. James Deetz’s (1977) words, “in small things forgotten,” draw attention to the textured fabric of daily life and especially to the material culture of the members of certain disadvantaged ethnic groups or ROBERT W. PREUCEL AND STEVEN R. PENDERY—Envisioning Utopia socioeconomic classes. Both of these answers are valid responses and, indeed, ones to which the authors subscribe. A third answer is suggested, however, that historical archaeology can offer a way of investigating how people and ideas recursively constitute one another through material culture. The focus here is on the materiality of the cultural landscape at Brook Farm. This landscape includes both the ideal visions of the organization of space and the physical expressions of those visions, what Amos Rapoport (1990) calls the “built environment.” The relations between the ideal and the real are particularly visible in utopian societies where new experiments in living are implemented (Tarlow 2002). In the case of Brook Farm, the focus is on understanding the social practices by which Transcendentalism and Fourierism were successively inscribed in the architecture and settlement pattern of the community. This understanding provides new insights into the daily lives of the members of the community and offers a partial answer to the perennial question posed by historians as to why the community adopted Fourierism. Brook Farm Archaeology The Brook Farm Historic Site is located in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, approximately 8 miles from downtown Boston (Figure 1). It is a multicomponent site encompassing 179 acres that had a series of notable historical period FIGURE 1. Location map of Brook Farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts. (Drawing by Steven Pendery, 1992.) 7 occupations. The best known of these is, of course, the Utopian period (1841–1847), the temporal focus of this article. Other significant occupations include its use as the Roxbury City Almshouse (1848–1855) to provide the indigent with housing and farm work, as Camp Andrew (1861) for the training of the 2nd Massachusetts Regiment, as the Martin Luther Orphans Home (1871–1943) to provide a home and religious education for orphans from the local Lutheran community, and as Brook Farm Home (1944–1948) for the care and treatment of emotionally disturbed youth. In 1988, the City of Boston purchased the property from the Lutheran Services Association, and today it is managed by the Metropolitan District Commission in the public interest. The site is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and is designated a Boston Landmark. Steven Pendery conducted the first archaeological research at Brook Farm in April 1990 as part of the Boston City Archaeology Program. The goals of his project were to locate and identify the specific archaeological resources of the project area (Pendery 1991). The methods involved testing likely site areas by means of test pits (50 x 50 cm) located at 5- and 10-m intervals along a series of transects. One prehistoric site and 11 historic period sites were identified and recorded, including the knoll prehistoric site, the Hive, the Hive outbuildings, the barn, the Eyrie, the Cottage, the Pilgrim House, the knoll historic site, the greenhouse, the workshop, and the phalanstery (Figure 2). In his report to the Massachusetts District Commission, Pendery (1991) concluded that the majority of these sites appeared to possess high levels of archaeological integrity and that the Utopian period sites should be studied more intensively to generalize about the development of Brook Farm between 1841 and 1847. In summer 1990, the authors established the Brook Farm Hive Archaeology Project to begin intensive excavations in the backyard area of the Martin Luther Orphans Home. Prior to the research reported on there, considerable confusion existed regarding the historical relationships between the Hive, the Roxbury City Almshouse, and the Martin Luther Orphans Home. Lindsay Swift (1900:39), for example, wrote that the Hive burned down only a year after use as the Roxbury City Almshouse (presumably in 1850). 8 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 40(1) FIGURE 2. Brook Farm utopian-period building locations. (Drawing by Steven Pendery.) He also stated that the Martin Luther Orphans Home was built on part of the foundations of the Hive (Swift 1900:39). Other sources, however, have identified the orphanage building itself as the original Hive (Sears 1912; Haraszti 1937). These contradictions served as the starting point for archaeological fieldwork. In the fall 1990 field season, a series of test pits (1 x 1 m) were excavated in the backyard area of the orphanage (Figure 3). Although none of the test pits in the targeted area yielded architectural remains, two units on the southern periphery produced unambiguous evidence for a house foundation. One contained deep layers of sand fill above a cobblestone floor, and another revealed a corner formed by the intersection of a brick and stone wall containing a loosely compacted brick and stone rubble fill also overlying a cobblestone floor. This feature proved to be the location of the colonial farmhouse christened “the Hive” by the Utopian community. During the 1991 summer field season, the foundations of the Hive were further exposed, and it was determined that its dimensions closely corresponded with its description in the City of Roxbury inventory (Joint Special Committee 1849). According to maps, deeds, and probate records, the original colonial period farmhouse was probably built sometime before 1700 by Edward Ward (Pendery 1991). It then passed down through the Richards, Matthews, Mayo, and Ellis families, with the latter selling it to George Ripley for use by his utopian community. Sometime during this succession, it seems to have been modified from a central chimney house to a central hall and parlor type with two chimneys and a kitchen ell. After taking possession of the house, the Brook Farm Association made a series of structural modifications to accommodate new members. One of these involved the construction of a wing addition adjacent to the kitchen ell. This addition housed a dining room, kitchen, laundry room, and nursery, with a shed and carriage rooms underneath. A trenching program during ROBERT W. PREUCEL AND STEVEN R. PENDERY—Envisioning Utopia FIGURE 3. Map showing the relationships between the Martin Luther Orphans Home and the Hive. (Drawing by Steven Pendery, 1992.) the 1992 field season provided archaeological evidence for a wing addition located on the west side of the house extending a small kitchen ell (Pendery and Preucel 1992a). Transcendentalism, the New Dawn of Human Piety Transcendentalism is a notoriously difficult philosophy to define. In part, this difficulty turns on the fact that it never comprised a unified belief system but, rather, was made up of a group of disparate ideas that were differentially interpreted by its advocates. In fact, there is no definitive list of Transcendentalists, although Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, William Henry Channing, George Ripley, Sophia Ripley, Elizabeth Peabody, Bronson Alcott, Henry David Thoreau, and Theodore Parker must surely be counted as among its leaders. Another difficulty is that many of the tenets espoused by the Transcendentalists are ones that we today take for granted, so completely has the legacy of this once-radical movement been absorbed into popular American 9 culture. To understand Transcendentalism as a social movement, it is thus necessary to ground it within its historical context. The shift from mercantile to industrial capitalism in the first half of the 19th century promised unrestricted growth and prosperity in the northeastern United States. Commercial and industrial expansion created new opportunities for speculation and profit. In the urban centers, however, ownership of property was dominated by elites. By 1840, the richest 1% of city dwellers owned 40% of all tangible property, with an even greater ownership of intangible property such as stocks and bonds (Henretta et al. 1987:331). One byproduct of industrial capitalism was the rise of wage labor. This fundamentally new social relationship severed the ties between employer and employee and household and workplace. Factory workers, for example, were no longer responsible for the entire production sequence, this knowledge instead being restricted to a few individuals. Russell Handsman and Mark Leone (1989) have argued that it is through this process of labor segmentation that one can find the source of the ideology of individualism. In Boston, this ideology was shaped by Unitarianism, the dominant religion of New England. The Unitarian church, itself a reaction to Orthodox revivalism, was founded upon the three pillars of reason, intellectual freedom, and moral duty (Rose 1981:11). Individualism was valued insofar as far as it was grounded in this trinity. With the rise of social stratification engendered by the profits from industrialization, the appeal of Unitarianism began to erode. Increasing numbers of individuals strayed from the church and began to criticize it openly. Even among the elite, debate occurred over whether religion was a way of life or just something to do on Sundays (Rose 1981:21). Members of the working class began to see their rights and interests as distinct from Christianity, which was seen as a tool of class oppression (Rose 1981:26). This challenge to Unitarianism was met by the development of an evangelical movement within the church, which targeted specific social ills. In 1834, the nine Unitarian churches of Boston united to sponsor missionary outreach to the poor. The philosophers of this evangelical Unitarian movement were known as the Transcendentalists (Rose 1981:38). They broke with Unitarianism 10 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 40(1) on a number of important doctrinal issues. They denied the validity of miraculous proofs and questioned the blind reliance upon tradition. Instead, they argued that religious institutions are human constructs and that all individuals possess the possibility of intuitive perception of spiritual truths by virtue of their common endowment of a soul. This position was extended to Biblical exegesis. Borrowing interpretive methods from the German idealists, Transcendentalists argued that the Bible was a historical document written by human authors in a less than enlightened age. These radical moves alienated the Unitarian church by threatening their liturgical teachings and challenging the existence of the priesthood. Ripley’s own unique contribution to this movement was to experiment with Transcendentalism as a theory for social reform. In 1841, he established the Brook Farm Association for Agriculture and Education to forge what he considered to be a more natural union between intellectual and manual labor by doing away with menial services. He wanted to provide the benefits of education and profits of labor to all. Ripley’s form of Transcendentalism is distinctly different from Emerson’s view, and it is significant that Emerson declined to become a member of the new community (Guarneri 1991: 45). This reluctance seems to have been based upon a disagreement regarding the relationship of the individual and society. In elevating the individual, Emerson argued that self-culture and self-education were prior to effective communal action. This philosophy was perhaps given its most idiosyncratic expression by Thoreau’s retreat to Walden Pond (Richardson 1986:56). In contrast, Ripley and the Brook Farmers felt that the ideal society could not be achieved by self-culture alone but, rather, required the expression of individuality within a communal setting through immersion in the lives of others. The only other Transcendental experiment in communal living, Bronson Alcott’s Fruitlands, combined elements from both Ripley’s and Emerson’s philosophies with Alcott’s own puritanical devotion to self-sacrifice. Natural Landscape and Associative Architecture It is no exaggeration to say that Transcendentalism imbued the very soil of Brook Farm. The selection of agriculture as the primary industry of the community was simultaneously a moral and an economic statement (Rose 1981: 138). Horticulture and animal husbandry were regarded as noble pursuits because of their close association with nature. Gardens were a particular source of delight to the community, and the garden near the Hive was playfully termed “Her Majesty’s Garden.” All members were to participate equally in work at tasks to be rotated each week (although in fact men were more commonly occupied in farm work and women in household duties and child care). All were paid the same fixed wage, and the working year was set at 300 days. During this period, records of individual work hours were apparently not kept. The community settlement pattern gradually evolved into a dispersed series of isolated residences linked together by the Hive, where common meals were taken. In 1843, Ripley relinquished his quarters at the Hive and built a separate residence for himself and his wife called the Eyrie. He chose the highest point of the property overlooking the farm, a practice strikingly reminiscent of a New England mill owner. This act set a precedent for individual members to build their own homes at different locations on the property. In the same month, new members erected the Cottage and the Pilgrim House along the ridge west of the Eyrie. This settlement pattern is captured in an oil painting by Josiah Wolcott, dated 1843 (Figure 4) (Osgood 1998). Two additional buildings were constructed by the community to accommodate the new sash-and-blind, shoemaking, Britannia ware, and flower industries (Figure 5). These were the workshop located near the Hive and the greenhouse situated behind the Cottage, both of which served double duty as residences. Transcendentalist architecture is characterized by a high degree of eclecticism. The major residential buildings constructed at Brook Farm constitute a veritable hodgepodge of architectural styles (Pendery and Preucel 1992b). The Hive was enlarged by a large ungainly wing extending from the kitchen ell, which dwarfed the original farmhouse. The Eyrie was built in an Italianate villa style, complete with low French windows, a decorative cornice, and terracing. The Cottage was a rural gothic structure with four gables ROBERT W. PREUCEL AND STEVEN R. PENDERY—Envisioning Utopia 11 FIGURE 4. Oil painting of Brook Farm, dated 1843 by Josiah Wolcott. (Courtesy of Mrs. Robert Watson.) and a central stairway. The Pilgrim House was a double house of the classical revival type. The overall effect of this mixture of styles must have been one of architectural confusion (Guarneri 1991:185). The Brook Farmers believed that individual growth and development could be best realized in communal association; therefore, their residential and domestic arrangements were structured to facilitate different kinds of social interactions. They favored dispersed residences but communal dining. Married couples and family units tended to be distributed in each of the buildings rather than being concentrated in any one. The only communal dormitory was the attic above the Hive, called Attica, which was reserved for bachelors. All of the community’s houses, except for the Hive, lacked kitchen facilities. This required members to gather in regular fashion to take their meals. Archaeological testing has confirmed the absence of dinnerware at all of the residences but the Hive. Each of the houses developed its own special character and personality due to its architectural style, its inhabitants, and its work associations. For example, the Eyrie was known as the place of culture and was home to George Ripley’s library and the setting for piano lessons given by John Dwight. The Cottage was built by Mrs. A. G. Alvord and came to be regarded as a place of education and learning. Amelia Russell (1900:63) writes, “(a)s it was decidedly the prettiest house on the place, it was thought the youthful mind would be impressed by it and lessons become easier.” The Pilgrim House, built by Ichabod Morton, was the location of the laundry and tailoring department and home to the editorial office of the Harbinger. It had a reputation for conviviality, and its large parlor was frequently used as a ballroom. 12 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 40(1) Fourierism, the Science of Social Perfection Fourierism is the name of a short-lived social movement born in France and introduced into America in 1840. It takes its name from its founder François Marie Charles Fourier (1772– 1837) who as a youth was deeply affected by the French Revolution of 1789. Fourier believed that conflict and suffering were the result of the perversion of natural human goodness by faulty social organization perpetuated by mercantile capitalism. He developed a complex psychological theory of instinctive drives and devised a social blueprint with detailed instructions for the size, layout, and industrial organization of ideal communities that accommodated differences in human personalities. Fourier embedded his critique of civilization within an elaborate theory of social evolution. For Fourier, human history was both progressive and regressive and is composed of 32 segments that can be subdivided into 4 phases. The first phase, lasting 5,000 years, is Infancy or Ascending Incoherence; the second, lasting 35,000 years, is Growth or Ascending Harmony; the third phase, lasting 5,000 years, is Decline or Descending Harmony; and the final phase, lasting 5,000 years, is Caudity or Descending Incoherence. He identified seven different stages within the Infancy phase. These are Confused Series, Savagery, Patriarchy, Barbarism, Civilization, Guarantism, and Simple Association. Significantly, these stages were defined in terms of the status of women. For example, Barbarism was characterized by the absolute servitude of women; Civilization was characterized by exclusive marriage and limited civil liberties of wives; and Guarantism was characterized by the development of an amorous corporation within which women would enjoy considerable sexual freedom. Fourier does not appear to have been especially interested in the earlier phases of social evolution, and most of his writings focus upon the transition from Civilization to Harmony. Fourier’s critique focused primarily on the institutions of commercial capitalism. For Fourier, the most egregious failing of civilization was its inability to resolve the problem of poverty. He noted that poverty was most severe in the advanced societies, saying that “the peoples of civilization see FIGURE 5. Britannia ware whale-oil lamp bearing a Brook Farm stamp. (Courtesy of Winterthur Museum) their wretchedness increase in direct proportion to the advance of industry” (Beecher 1986:197). He identified three causes for the persistence of poverty. The first of these was wastefulness, or the inefficiency of capitalist methods of production and consumption. He singled out the French family farmer, observing that the use of communal plots, storage facilities, and kitchens would greatly reduce the amount of drudgery. The second cause was that production was uncontrolled and depended only on the profit motive. Because of competition among producers, overproduction periodically threw thousands of people out of work. The third cause was the inefficient use of human potential, meaning that the vast majority of workers were employed in jobs that were either redundant or were a drain on the orderly functioning of society. Especially reprehensible was the merchant, whom Fourier saw as a parasite ROBERT W. PREUCEL AND STEVEN R. PENDERY—Envisioning Utopia that only diverted capital from agriculture and industry. According to Fourier, the root of these injustices was the repression of individual desires by existing social institutions. To resolve this issue, he developed his theory of passional attraction, the idea that all human desires are governed by natural laws. He approached this problem from a positivistic philosophy and in his mind made a scientific breakthrough on the order of Newton’s discovery of gravity, an analogy that he often employed. He defined passionate attraction as “the drive given us by nature prior to reflection, and it persists despite the oppression of reason, duty, prejudice, etc.” (Beecher 1986:225). Fourier identified 12 different passions growing from three branches of the tree of unityism. The luxurious passions were the five senses (sight, smell, taste, touch, hearing); the affective passions were love, friendship, ambition, familism; and the distributive passions were cabalist, butterfly, and composite. These represented the alphabet of Fourier’s social language, and his many writings are attempts to work out a passional grammar complete with its own syntax. Fourier’s ideal community was called a phalanx. It was to be composed of exactly 1,620 people or twice the number of people necessary to ensure an adequate complement of the 810 passional personality types. Ideally it was to be situated upon a square league of land in a rural setting and located within a day’s ride of a large city for easy access to a market. The site was to be relatively hilly with a stream and possess soils and a climate suitable for the cultivation of a wide variety of crops. Dominating the phalanx was the phalanstery, a massive building adorned with colonnades, domes, and peristyles resembling a cross between a palace and a resort hotel. Symmetrical wings segregated workshops, music practice rooms, and playrooms (noisy activities) from visitor quarters, entertainment halls, and communications centers (less noisy activities). Two architectural innovations were pioneered by Fourier: the use of special rooms reserved for work groups known as seristries and covered street galleries linking the phalanstery to adjacent buildings. One of Fourier’s disciples, Victor Considerant, drafted an architectural rendering of such a structure that looked remarkably like the palace of Versailles. 13 In the United States, Fourierism caught the imagination of numerous social reformers seeking to merge diverse social critiques into a coherent workable system. The age of Fourierism in American was precipitated by Albert Brisbane, the idealistic son of a New York merchant who had been introduced to Fourier’s writings in 1833 while on a trip through Europe. He was so moved by what he read that he sought out Fourier for further instruction and became a convert. Brisbane wrote that his sole goal in life was to “transmit the thought of Charles Fourier to my countrymen” (Guarneri 1991:30). After a delay of several years due to illness, Brisbane took up the cause in earnest. In 1840, he published The Social Destiny of Man, a translation of and commentary on Fourier’s thought (Brisbane 1840). He also enlisted the support of Horace Greeley who was just beginning his newspaper career. In March 1842, Greeley sold Brisbane a front-page column in the New York Tribune that became a vehicle for expounding the virtues of Fourierism. This proved to be a remarkably successful propaganda tool, and in the following 30 years more than 29 Fourierist phalanxes, unions, and societies were established across the United States (Table 1). The impact of Fourierism upon the Transcendentalists was initially slight. Reacting against its formality, Ripley wrote in 1842 that he was not attracted to a science that “starts with definite rules for every possible case” (Rose 1981:143, note 88). This sentiment was echoed by Emerson who wrote, “Fourier has skipped no fact but one, namely, Life” (Cayton 1989:205). However, by 1843, it soon became clear that the organization of labor at Brook Farm based upon voluntary measures was not working. Because of poor yields, the community was forced to take out additional mortgages and institute a retrenchment program. Ripley was thus searching for a way to increase productivity while being faithful to his desire to place intellectual and manual labor upon a more natural footing. The turning point was the Social Reform Convention held in Boston on 27 and 28 December 1843, a platform for Fourierist advocates that was heavily attended by Brook Farmers. In 1844, after considerable discussion, the community reincorporated themselves as the Brook Farm Phalanx, the 14 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 40(1) TABLE 1 FOURIERIST COMMUNITIES IN THE UNITED STATES 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Name Location Dates Social Reform Unity Jefferson Co. Industrial Association Sylvanian Association Moorehouse Union North American Phalanx LaGrange Phalanx Brook Farm Phalanx Clarkson Association Bloomfield Union Association Leraysville Phalanx Ohio Phalanx Alphadelphia Association Sodus Bay Phalanx Mixville Association Ontario Union Clermont Phalanx Trumbull Phalanx Wisconsin Phalanx Iowa Pioneer Phalanx Philadelphia Industrial Association Columbian Phalanx Canton Phalanx Integral Phalanx Spring Farm Phalanx Pigeon River Fourier Colony Raritan Bay Union Reunion Phalanx Fourier Phalanx Prairie Home Colony Barrett, PA Cold Creek, NY Darlingville, PA Pisceo, NY Red Bank, NJ Mongoquinog, IN West Roxbury, MA Clarkson, NY North Bloomfield, NY Leraysville, PA Bell Air, OH Galesburgh, MI Sodus, NY Mixville, NY Bates Mills, NY Rural and Utopia, OH Phalanx Mills, OH Cereso, WI Scott, IO Portage, IN Zanesville, OH Canton, IL Lick Creek, IL Spring Farm, WI Pigeon River, WI Perth Amboy, NJ Dallas, TX Sparta, IN Silkville, KA 1842–1843 1843–1844 1843–1844 1843–1844 1843–1855 1843–1847 1844–1847 1844–1845 1844–1846 1844–1845 1844–1845 1844–1847 1844–1846 1844–1845 1844–1845 1844–1846 1844–1848 1844–1850 1844–1845 1845–1847 1845–1847 1845 1845–1847 1846–1869 1846–1847 1853–1857 1855–1859 1858 1869–1892 Source: Hayden (1976) and Guarneri (1991:table 1). third of more than 16 phalanxes established in America. The immediate outcome of this was a dramatic influx of new members, most of which were lower-class tradesmen and women (Rose 1981:152; Guarneri 1985). Phalansterian Landscape and Communitarian Architecture The first steps toward transforming Brook Farm into a Fourierist community involved the reorganization of labor and the construction of a phalanstery. Following the prescriptions of Fourier, the Brook Farmers instituted a work program of series and groups. Three primary series were established—the agricultural, mechanical, and domestic industries, each of which was subdi- vided into a number of groups. For example, the domestic series was composed of dormitory, constitory, kitchen, washing, ironing, and mending groups. The chief of each group was to be elected each week, and one of his or her main duties was to keep a record of the work done by each member of the group. Great emphasis was placed upon the interchangeability of work, so that any member who became bored with one task could easily transfer to another group. The series showed mixed results because of the lack of specialized knowledge and experience and the limited availability of capital. The carpentry group acquired a lessthan-distinguished reputation on the Boston market. It appears that the lumber used was not properly seasoned, with the consequence ROBERT W. PREUCEL AND STEVEN R. PENDERY—Envisioning Utopia that doors purchased from Brook Farm had an unfortunate tendency to warp and shrink (Swift 1900:43). The cattle group conducted a curious experiment in animal husbandry. Ripley tried to wean a calf by replacing milk with hay tea. The calf died. The attempt by the nursery group to plant a large flower garden and sell flowers on the Boston market failed due to poor soil quality. Yet even with this litany of setbacks, some groups were successful, and in 1844 the community turned a modest profit for the first time in its history (Rose 1981:150). Fourierist architecture is characterized by formalism and institutionalized control. The Brook Farm Phalanstery, like all phalansteries built in America, was a vernacular building. A member wrote that it was called a phalanstery, “not that it resembled one, but more out of deference to the idea of one” (Codman 1894:186). Despite this homespun quality, it was an imposing building, three stories high and capable of being expanded (Codman 1894:98). The basement contained a large kitchen, a bakery, a dining hall capable of seating 300–400 people, two public salons, a hall, and a lecture room. Unfortunately, no visual representations of the phalenstery are extant beyond Josiah Wolcott’s 1844 painting that appears to show it under construction (Figure 6), 15 FIGURE 6. Oil painting of Brook Farm, ca. 1844–1846 by Josiah Wolcott. (Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.) but it is known to have served as the model for the phalanstery erected at the North American Phalanx in Red Bank, New Jersey (Figure 7). The archaeological testing programs in 1990 and 1994 have conclusively identified the phalanstery cellar, but unfortunately only half of it remains intact due to gravel quarrying activities during the almshouse and Lutheran periods (Pendery 1991). The Brook Farm Phalanstery was to physically house and symbolically represent a new kind of FIGURE 7. The Phalanstery at the North American Phalanx, ca. 1900 (from Hayden 1976:figure 6.15). 16 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 40(1) communal living, one that provided residence for both individuals and families. The attic was divided into single rooms for the housing of bachelors. Its second and third stories were each divided into seven family suites that consisted of a parlor and three sleeping rooms. Fourier’s covered street galleries were reworked into external passageways running the length of the building and connecting these suites. Presumably, members of different social classes were to reside in alternate suites. But it is likely that residence rules would have been relaxed for wealthy stockholders desiring even greater privacy. Marcus Spring, one of the benefactors of Brook Farm, built separate cottage-style houses immediately opposite the community phalanstery at both the North American Phalanx and the Raritan Bay Union, creating a rather discordant effect (Hayden 1976). The Brook Farm Phalanstery posed a sharp contradiction with the existing housing stock. In discussing its setting on a hill immediately below the Eyrie, Russell (1900:92) wrote, “[i]f it did not entirely obscure the Aerie, it certainly spoiled the effect produced by that building when seen from a distance.” Some members believed that the new building should be large enough to house the entire community, implying that the older houses should no longer be used as residences. Others, however, argued that that they should be kept intact to accommodate the new members that would be inspired to join. The implications of this decision for creating a new set of social tensions between the original members and the arrivals, however, went unrealized because the phalanstery was never inhabited. On Tuesday, 3 March 1846, the very week it was due to be completed, it burned to the ground. A day after the fire, Marianne Dwight (1928:148) wrote, “a part of the stone foundation stands like a row of gravestones—a tomb of the Phalanstery—thank God, not a tomb of our hopes!” Test excavations at the site of the phalanstery during summer 1994 found numerous examples of fused window glass that provides direct evidence for the fire. Conclusion American utopian communities were important to the extent that they identified significant social issues and subjected them to critique despite the actual longevity of any particular community. Attempts at reform were often effected by transforming the landscape so that the physical remains of these practices embody information about specific responses to these issues. Architecture and settlement directed and shaped the ongoing attempts to balance conflicting tensions of agricultural and industrial development, egalitarian and authoritarian decision making, individual and communal living. Archaeological research at Brook Farm is providing valuable information on these practices during its Transcendentalist and Fourierist incarnations. There are no extant plans of the community. All of the original buildings have since been destroyed, and many of their locations lost. Research has identified the sites of all of the utopian-period buildings and generated the first accurate map of the settlement. Transcendentalism was above all else an extremely flexible doctrine, one that tolerated a considerable degree of latitude among its advocates. On the surface, nothing would seem to be more different from Brook Farm than Bronson Alcott’s consocial family at Fruitlands and Thoreau’s isolation at Walden, yet all three were inspired by similar critiques of industrial capitalism grounded in evangelical Unitarian values (Francis 1997). There is a sense of intellectual bricolage underlying the movement where ideas from German idealists, British romanticists, and French reformers are all mixed together with a dash of New England pietism thrown in for good measure. At Brook Farm, this “working things out as they go” philosophy signified a commitment to egalitarianism where individual self-fulfillment could only be achieved through engagement within a social group. This view was embedded in the landscape through the moral elevation of agriculture and the egalitarian program of volunteer labor. It is also to be seen in the unplanned, almost haphazard, expansion of settlement and the use of eclectic architecture, emphasizing individualism. Fourierism, by contrast, was a much more rigid, authoritarian system that specified all aspects of the ideal society, even down to appropriate sexual partners. This and other controversial elements were carefully edited out by Fourier’s proselytizers for an American ROBERT W. PREUCEL AND STEVEN R. PENDERY—Envisioning Utopia audience, resulting in a translation that retained the strength of Fourier’s vision but lacked many of his psychological insights. Nonetheless, the expurgated version was well received and served as a social blueprint for the two dozen Fourierist phalanxes founded across the United States. This “sacred text” meant that there was much less leeway for experimenting with social relations. Especially problematic was the question of class that Fourier regarded as a natural condition of human existence. At almost all American phalanxes, tensions developed externally between wealthy absentee stockholders and resident members and internally between lower-class tradespeople and the “aristocratic element.” At Brook Farm, the adoption of this highly structured organization was reflected in and maintained by the expansion of industry, the proposed centralization of activities in the phalanstery, and the standardization of communal architecture. The central question that has occupied historians and literary scholars alike is why did the community abandon its Transcendentalist principles and adopt Fourierism? There is no wholly satisfactory answer to this, but perhaps the question is misstated in its stark opposition. Perhaps Transcendentalism was not entirely abandoned, and elements of it coexisted peaceably alongside Fourierism. Certainly hints of this can be found in the writings of Dwight and Russell. Although some members left the community when it reincorporated as a phalanx, it is significant that a small group remained that never fully accepted the tenets of Fourier and was never comfortable with the new tradespeople. According to Russell (1900:99), “[o]ur meetings in the dining-room (of the Hive) were quite pleasant, but they did not seem the same as the social gatherings of other times. They were too large; our numbers had now increased to much over a hundred, and of course the homelike appearance of our little parties was lost in the crowd around us.” Research suggests that the dispersed housing stock built during the Transcendentalist period actually perpetuated certain Transcendentalist habits of thought and action that tended to value individualism and democracy. From this perspective, Brook Farm was a Fourierist phalanx more in name than in fact. 17 Acknowledgments We would like to acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for their assistance in various phases of our research. These include Judith McDonough, Brona Simon, and Constance Crosby of the Massachusetts Historical Commission and Illyas Bhatti, Tom Mahlstedt, and William Stokinger at the Metropolitan District Commission. Bob Murphy, president of the West Roxbury Historical Society, and Ralph Moeller, director of the Gethsemane Cemetery, provided invaluable local assistance. We would particularly like to thank Peter Buck, dean of the Harvard University Summer School, Lawrence Buell of Harvard University, and Rick Delano of Villanova University for their advice and support. We also wish to thank John Shea, William Griswold, and John Fox, who served ably as our teaching assistants. Special thanks go to Nancy Osgood for her assistance in fieldwork and historical research, Peter Drummey of the Massachusetts Historical Society for the use of the images of the two Wolcott paintings, Dorothy Hayden for the use of the image of the North American Phalanx, and Susan Newton of the Winterthur Museum for the use of the image of the Brook Farm oil lamp. Finally, we would like to express our appreciation to the numerous Harvard University students and volunteers who participated on the project. References BEECHER, JONATHAN 1986 Charles Fourier: The Visionary and His World. University of California Press, Berkeley. BRISBANE, ALBERT 1840 The Social Destiny of Man; or, Association and Reorganization of Industry. C. F. Stollmeyer, Philadelphia, PA. BUELL, LAWRENCE 1986 New England Literary Culture: From Revolution through Renaissance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA. CAYTON, MARY KUPIEC 1989 Emerson’s Emergence: Self and Society in the Transformation of New England, 1800–1845. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill. 18 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 40(1) CODMAN, JOHN 1894 Brook Farm, Historic and Personal Memoirs. Arena Publishing Co., Boston, MA. DEETZ, JAMES 1977 In Small Things Forgotten: The Archaeology of Early American Life. Anchor Press/Doubleday, Garden City, NJ. DELANO, STERLING F. 1983 Harbinger and New England Transcendentalism: A Portrait of Associationism in America. Farleigh Dickinson University Press, London, England. DWIGHT, MARIANNE 1928 Letters from Brook Farm, 1844–1847, Amy L. Reed, editor. Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY. FRANCIS, RICHARD 1997 Transcendental Utopias: Individual and Community at Brook Farm, Fruitlands, and Walden. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. GUARNERI, CARL 1985 Who Were the Utopian Socialists? Patterns of Membership in American Fourierist Communities. Communal Societies 5(Fall):65–81. 1991 The Utopian Alternative: Fourierism in NineteenthCentury America. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. HANDSMAN, RUSSELL G., AND MARK P. LEONE 1989 Living History and Critical Archaeology in the Reconstruction of the Past. In Critical Traditions in Contemporary Archaeology: Essays in the Philosophy, History, and Socio-Politics of Archaeology, Valerie Pinsky and Alison Wylie, editors, pp. 117–135. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA. HARASZTI, ZOLTAN 1937 The Idyll of Brook Farm as Revealed by Unpublished Letters in the Boston Public Library. Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Boston, MA. HAWTHORNE, NATHANIEL 1852 The Blithedale Romance. Ticknor and Fields, Boston, MA. 1932 American Notebooks, Randall Stewart, editor. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. HAYDEN, DOLORES 1976 Seven American Utopias, The Architecture of Communitarian Socialism, 1790–1975. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. HENRETTA, JAMES A., W. ELLIOT BROWNLEE, DAVID BRODY, AND SUSAN WARE 1987 America’s History to 1877. Dorsey Press, Chicago, IL. JOINT SPECIAL COMMITTEE (CITY OF ROXBURY) 1849 Report of the Joint Special Committee on the Buildings at Brook Farm and a New Almshouse. City Document, No. 6, City of Roxbury, Roxbury, MA. MYERSON, JOEL 1978 Brook Farm: An Annotated Bibliography and Resources Guide. Garland Publishing, New York, NY. OSGOOD, NANCY 1998 Josiah Wolcott: Artist and Associationist. Old Time New England 76(264):5–34. PENDERY, STEVEN R. 1991 Archaeological Testing at Brook Farm. Report to the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston, from Steven R. Pendery, Boston City Archaeology Program, Boston, MA. PENDERY, STEVEN R., AND ROBERT W. PREUCEL 1992a The Archaeology of Social Reform: Report of the Excavations of the Brook Farm Hive Archaeological Project. Report to the Massachusetts Historical Commission, Boston, from Steven R. Pendery and Robert W. Preucel, Boston City Archaeology Program, Boston, MA, and Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. 1992b Utopian Landscapes of Brook Farm. Paper presented at the 25th Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology, Kingston, Jamaica. RAPOPORT, AMOS 1990 The Meaning of the Built Environment. University of Arizona Press, Tucson. RICHARDSON, ROBERT D., JR. 1986 Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind. University of California Press, Berkeley. ROSE, ANNE C. 1981 Transcendentalism as a Social Movement, 1830–1850. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. RUSSELL, AMELIA E. 1900 Home Life of the Brook Farm Association. Little, Brown and Co., Boston, MA. SEARS, JOHN VAN DER ZEE 1912 My Friends at Brook Farm. Desmond Fitzgerald, New York, NY. SUMNER, ARTHUR 1894 A Boy’s Recollection of Brook Farm. New England Magazine 10(May):309–313. SWIFT, LINDSAY 1900 Brook Farm: Its Members, Scholars, and Visitors. Macmillan, New York, NY. TARLOW, SARAH ROBERT W. PREUCEL AND STEVEN R. PENDERY—Envisioning Utopia 2002 Excavating Utopia: Why Archaeologists Should Study “Ideal” Communities of the Nineteenth Century. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 6(4): 209–323. ROBERT W. PREUCEL DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA 33RD AND SPRUCE STS. PHILADELPHIA, PA 19104 STEVEN R. PENDERY NORTHEAST REGION ARCHEOLOGY PROGRAM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE 115 JOHN ST. LOWELL, MA 01852-1195 19