Private Provider Networks: The Role of Viability in

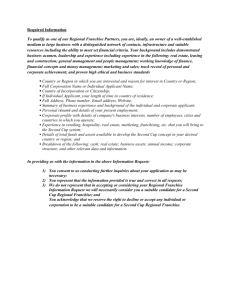

advertisement