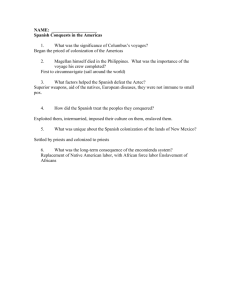

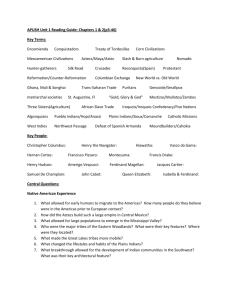

black conquistadors - ChristinaProenza.org

advertisement