a guide to trade support

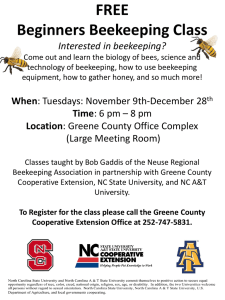

advertisement