The 'Open Window' Study

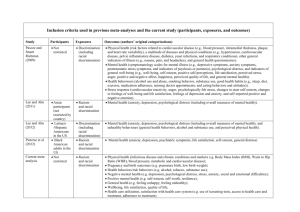

advertisement