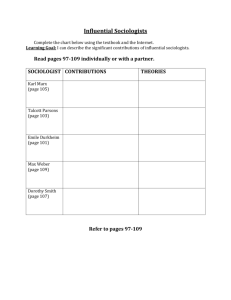

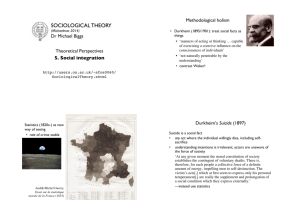

The Socioemotional Foundations of Suicide: A

advertisement