Leading a Vocabulary Awakening

advertisement

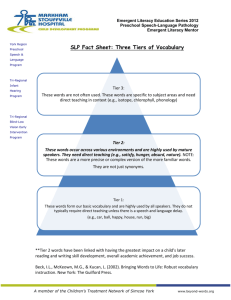

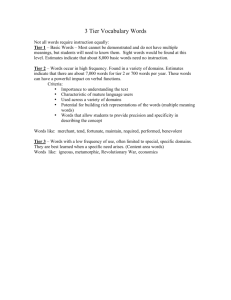

Leading A Vocabulary Awakening Equipping Teachers and Students Dr. Lori Meier, Literacy Trainer (meierl@brevard.k12.fl.us) Office of Title I - Brevard Public Schools Key Questions z z z z How can we nurture a vocabulary awakening in our schools? How can we dramatically increase the amount of time children are intellectually engaged in vocabulary learning? How can we provide fresh, authentic instruction when learners have limited background knowledge? How do we decide what vocabulary learning is useful? Robust Vocabulary Instruction z z With great urgency we are understanding the effects and consequences of limited student vocabularies. Formal education is acquired largely through language and always builds on what the learner already knows (their schema) and has vocabulary for. (Adams, 1990) Robust Vocabulary Instruction z The differences between number of words known by students with poor vocabularies versus those with rich vocabularies is extensive, grows over time, and is evident early. (Baker, Simmons, & Kameenui, 1995) Robust Vocabulary Instruction 5,000 4,500 Vocabulary Size and SES 4,000 3,500 Profound vocabulary differences primarily attributed to socio-economic conditions[1] 3,000 2,500 2,000 1,500 1,000 500 0 Grade 1 Grade 2 Middle Class Grade 3 Lower SES [1] Dr. Jerry L. Johns, National Consultant in Reading Robust Vocabulary Instruction z z On an average, a preschool child from a professional family is provided annually with 11 million words, a working-class family 6 million words, and a welfare family 3 million words. (Hart & Risley, 1995) The vocabulary gap widens over time. (White et al, 1990) - Grade 1 differences between middle SES schools & low SES schools about 1300 to 2300 words - Grade 3 differences jump to about 5000 words Robust Vocabulary Instruction z z All the available evidence indicates that there is little emphasis on the acquisition of vocabulary in school curricula. This is a high priority - but not just any one-dimensional, traditional vocabulary instruction will do. It must be robust, vigorous, strong, and powerful. (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan 2002) The relationship between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension is strong. The continued development of strong reading skills is the most effective independent word learning strategy. (Baker, Simmons, & Kameenui, 1995) Robust Vocabulary Instruction z z Students who don’t have large vocabularies or effective wordlearning strategies often struggle to achieve comprehension. Their bad experiences with reading set in motion a cycle of frustration and failure that continues. (www.prel.org) Because these students don’t have sufficient word knowledge to understand what they read, they typically avoid reading. Because they don’t read very much, they don’t have the opportunity to see and learn very many new words. Robust Vocabulary Instruction z z This sets in motion the “Matthew Effects” Stanovich’s (1986) application of a verse from Matthew, “the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.” In terms of vocabulary development, good readers read more, become better readers, and learn more words and vice versa A Tradition of Tradition z z (1995) Watts study: 87% of vocabulary taught only as a pre-reading strategy (presented definitional meaning) and only seen as essential for the specific story to be read Research regarding basal readers treatment of vocabulary is limited and aging. Overall, it has improved but there is much room for improvement (Graves, 2006) A Tradition of Tradition z Recent study of 23 4th-8th grade classrooms: 12% of time devoted to vocabulary, only 1.4% of content area time (Scott, Jamieson-Noel, & Asselin, 2003) A Tradition of Tradition z z z Research-based methods of vocabulary instruction not generally known or employed by teachers (Graves, 2006) We know too much to say we know too little, and we know too little to say that we know enough. (Baumann & Kameenui, 1991) The Teaching Gap: Our cultural scripts for teaching begin early: roles, patterns of teaching, and expectations are already developed (Stigler & Hiebert, 1999). We sustain our cultural systems in accord with our beliefs and values about learning and students. Our Approach To provide instructional strategies that: z advocate teaching vocabulary multi-dimensionally z foster student “skills and strategies” of vocabulary learning z avoid “thin” short-term study of words (i.e. dictionary only) Our Approach To provide instructional strategies that: z support “thick” robust instruction: activating prior knowledge (schema), contextual examples of the word, conversation, comparison/contrast, and multiple encounters z encourage word consciousness and talk z also include academic vocabulary learning Our Approach Framework: • On-going professional development offered to teachers in Title I schools with materials provided • At least 4-6 sessions throughout the year • Collaboration with reading coaches and administrators • One school wide BAV start up with January launch in process, 45 teachers, K-6 • Do I Really Have to Teach Vocabulary? (4 day summer institute) Our Approach Building Academic Vocabulary (Marzano & Pickering, 2005) Tier 2 Word Study (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan 2002) Foster Word Consciousness Shifting the mindset first … Mining our own learning minds, looking inward towards our own vocabulary learning and word consciousness z Focus more on the process not the products z Understanding and acknowledging how to manage recent changes and mandates while still seeking “best practice” replacement methods z Tier Two Instruction "This little book is a gem. It shows how teachers can teach word meanings so powerfully that students of all ages will be able to grasp an author's meaning or communicate their own more effectively. The book offers a well-organized and first-rate plan for teaching vocabulary, presented by a team of researchers with a genuine grasp of the practical.“ --Timothy Shanahan, PhD, Center for Literacy, University of Illinois at Chicago Tier Two Instruction "Bringing Words to Life lives up to its title. It made me want to gather a group of kids immediately, so I could start putting these sensible, practical, novel, and intriguing ideas about building vocabulary into practice. Beck, McKeown, and Kucan show how much fun learning words and teaching words can be. Every early childhood and elementary teacher should have this book on their bedside table for inspirational reading.“ --Catherine E. Snow, PhD, Graduate School of Education, Harvard University Tier 1, 2, & 3 Words Tier 3 Domain Specific Tier 2 Mature Words Tier 1 Basic Words Frequency of use is low. Domain specific words. Examples: isotope, lathe, refinery High frequency words for the mature language learner. Examples: absurd, industrious, fortunate Consists of the most basic words. Rarely require instruction to their meaning at school. Examples: clock, baby, happy Tier Two Instruction Excerpt from “My Father the Entomologist” by Edwards, 2001, p. 5 “Oh, Bea, you look as lovely as a longhorn beetle lifting off for flight. And I must admit your antennae are adorable. Yes, you’ve metamorphosed into a splendid young lady.” Bea rolled her eyes and muttered, “My father, the entomologist.” “I heard that, Bea. It’s not nice to mumble. Unless you want to be called a Mumble Bea!” Bea’s father slapped his knee and hooted. Bea rolled her eyes for a second time. . Tier Two Instruction Excerpt from “My Father the Entomologist” by Edwards, 2001, p. 5 “Oh, Bea, you look as lovely as a longhorn beetle lifting off for flight. And I must admit your antennae are adorable. Yes, you’ve metamorphosed into a splendid young lady.” Bea rolled her eyes and muttered, “My father, the entomologist.” “I heard that, Bea. It’s not nice to mumble. Unless you want to be called a Mumble Bea!” Bea’s father slapped his knee and hooted. Bea rolled her eyes for a second time. . Tier Two Instruction Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Shared Read -highlight words Vocabulary Activities Vocabulary Activities Vocabulary Activities Assessment 3-6 K-3 Text Talk from Scholastic Developed our own booklist for 3-6 Building Academic Vocabulary • Marzano & Pickering describe a six-step process for content area vocabulary. • The first three steps are to assist the teacher in direct instruction of the term. The last three steps are to provide the learner practice and reinforcement. Building Academic Vocabulary • • • • Word Selection Student Academic Notebook Note-taking Form Games and Review Building Academic Vocabulary z z z Step 1: The teacher will give a description, explanation, or example of the new term. Step 2: The teacher will ask the learner to give a description, explanation, or example of the new term in his/her own words. Step 3: The teacher will ask the learner to draw a picture, symbol, or locate a graphic to represent the new term. Building Academic Vocabulary z z z Step 4: The learner will participate in activities that provide more knowledge of the words in their vocabulary notebooks. Step 5: The learner will discuss the term with other learners. Step 6: The learner will participate in games that provide more reinforcement of the new term. Building Academic Vocabulary z Examples … Fostering Word Consciousness Refers to a keen awareness, interest, and appreciation of words (linguaphiles, being word savvy) z Recently articulated in the research (Anderson & Nagy, 1992; z Scott & Nagy, 2004; Graves, 2006) z Correlation to metalinguistic awareness (the ability to recognize and think about the various features of language and words: morphological makeup, appropriateness in various contexts, etc.) Fostering Word Consciousness An appreciation of the power of words and an understanding of why certain words are used in a situation by speakers or authors z An interest in learning new words z Teachers can model and recognize adept diction, use word of the day or word wizards, and promote word play z Some lessons from the road… z Classroom Application Examples Where to learn more… z z z z z z z z z z z Anderson, R. C., & Nagy, W. E. (1991). Word meanings. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 2, pp. 690-724). New York: Longman. Baker, S. K., Simmons, D. C., & Kameenui, E. J. (1995). Vocabulary acquisition: Synthesis of the research. Technical Report 13. National Center to Improve the Tools of Educators. University of Oregon. Available from this internet source: http://idea.uoregon.edu/~ncite/documents/techrep/tech13.html Baumann, J. F., & Kameenui, E. J. (1991). Research on vocabulary instruction: Ode to Voltaire. In J. Flood, J. J. D. Lapp, & J. R. Squire (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching the English language arts (pp. 604-632). New York: MacMillan. Beck, I. L., McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York: Guilford Press Beck, I., & McKeown, M. (1991). Conditions of vocabulary acquisition. In R. Barr, M. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 2, pp. 789-814). New York: Longman. Graves, M. F. (1986). Vocabulary learning and instruction. In E. Z. Rothkopf (Ed.), Review of research in education , 13 , 49-89. Graves, M. F. (2006). The vocabulary book: Learning and instruction. New York: Teachers College Press. Marzano, R. J. & Pickering, D. J. (2005). Building Academic Vocabulary: Teacher’s Manual. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. Nagy, W., & Anderson, R. C. (1984). How many words are there in printed school English? Reading Research Quarterly , 19 , 304-330. Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly , 21 , 360-406. White, T. G., Graves, M. F., & Slater, W. H. (1990). Growth of reading vocabulary in diverse elementary schools: Decoding and word meaning. Journal of Educational Psychology , 82 (2), 281-290.