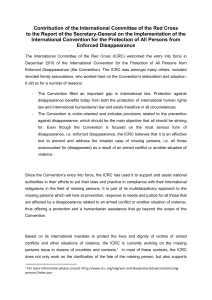

Accompanying families of missing persons in relation to armed

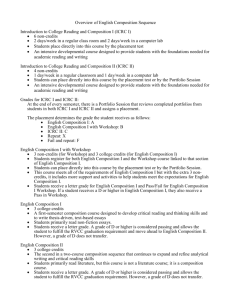

advertisement