(PDF, Unknown)

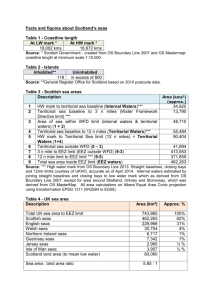

advertisement

No. 2007-02 The Bangsamoro Territory: Explanatory Argument for Territorial Waters Michael O. Mastura Institute of Bangsamoro Studies Institute of Bangsamoro Studies Occasional Paper No. 2007-02 December 2007 The views expressed in the Occasional Papers are those of the author(s) and not necessarily of the IBS. The Bangsamoro Territory: Explanatory Argument for Territorial Waters By Michael O. Mastura Datu Michael O. Mastura is a lawyer, historian and politician. He is the president of Sultan Kudarat Islamic Academy Foundation College and twice elected representative of the first congressional district of the Province of Maguindanao and Cotabato City to the Philippine Congress. He was also elected delegate to the 1971 Philippine Constitutional Convention. He is an accomplished author who published several books and articles in national and international journals. Atty. Mastura is a member of the peace panel of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) negotiating peace with the Government of the Republic of the Philippines. The Institute of Bangsamoro Studies (IBS) is a non-profit and non-government institution the functions of which are to carry out research on Bangsamoro history, culture, politics, economy and contemporary affairs; conduct trainings to capacitate the youth, women and the poor; and render community services to poor and conflict affected communities. Institute of Bangsamoro Studies Hadji Daud Bldg., Campo Muslim Cotabato City 9600, Philippines Telefax: +63-64 4213551 Email: morostudies@yahoo.com 2 Institute of Bangsamoro Studies Occasional Paper No. 2007-02 The Bangsamoro Territory: Explanatory Argument for Territorial Waters Michael O. Mastura Brief Background The nationally defined territory of the Philippines consists of the public domain which is made up of areas that were ceded by Spain to the United States in the Treaty of Paris of 1898. The operative stipulation concerning the cession reads in part: “Spain cedes to the United States the archipelago known as the Philippine Islands, and comprehending the islands within” certain lines drawn along specified degrees longitude East and latitude North. There is opposition to the Philippine claim of sovereignty over its inter-island waters to the effect that the waters comprehended within the imaginary lines mentioned in the Treaty were not included. This view holds that only the islands were transferred but not the intervening waters. 1 In this context, the Bangsamoro people more so have raised the question of the lack of plebiscitary consent on their part as the chief flaw in the framework of cession. International law attaches a portion of maritime territory consisting of what the law called “territorial waters” to States whose land is washed by the sea. Beyond its land domain and its internal waters that belt of territorial sea adjacent to the coast, which is described as “territorial sea”, forms part of the coastal State. In regard to this point, Philippine stand as to the extent of the territorial sea to be fixed as limit is open. The Philippines is not a party to the Geneva Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. But it signed the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) on 10 December 1982 and ratified it on 8 May 1984. The Philippine Government adopted in 1992 a national policy on the Law of the Sea based on UNCLOS although the Convention became effective only on 16 November 1994. 1. The Problem of Delimitation Reformulated Within the law of-the-sea concept are included the definition of a state’s territorial waters, the right of states to fish the oceans and to mine underneath the seas, and the right of states to control navigation. Because of some problems on the breadth or limits of the 1 Territorial delimitation has preoccupied debates on the National Territory during the Constitutional Conventions that drafted the 1935 Constitution and 1973 Constitution. The expressions in the 1973 Constitution make no reference to treaties and define the country as an archipelago and its internal waters. 3 territorial sea, the Philippine delegation proposed that it be an exemption to the 12-mile rule. Thus territorial waters are claimed under historic and legal title. Under the Convention, a major change is its extension of a State’s territorial waters from 3 to 12 nautical miles. In case of an archipelagic State, it may apply a system of baselines to its archipelagic waters the length of which shall not exceed 100 nautical miles, except for enclosing up to 125 sea miles. A definitive determination of the extent of Philippine territorial sea and of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is vital in positing a legal regime. The most crucial issue is whether to perpetuate errors in old delimitation of the boundary lines of the Philippines: Should the national territory definition qualify a new breadth of its territorial waters pursuant to the Treaty Limits? Should the island-country establish new limits of territorial sea in conformity with the provisions of the UNCLOS? There is an imperative to redefine the Philippine archipelagic baselines from which the territorial waters are measured. 2 First of all, the Treaty Limits that almost all other countries reject 3 still form the basis of definition of territory in the Philippine Constitution. In the second place, its system of enclosure increases that national “territory” approximately 2.8 fold. Considerations: Arguably the Treaty of Paris applies only to the islands. And so waters within the baseline are internal waters. It follows that waters at the outermost point of the straight baselines up to the Treaty Limits—corresponding to the constitutional delineation—are territorial waters. 2. Juridical Status of Sea Areas The delimitation of sea areas has always an international aspect (AngloNorwegian Fisheries Case, I.C.J. Reports 1951). The extension of State competence over the coastal waters, marine areas, and special rights within the maritime domain has evolved practices of States with legal implications. The extent of the maritime territory of the Philippines was stated in the Note Verbale of 7 March 1955 to the UN Secretary General before the adoption of the four Conventions of 1958. 2 Ambassador Rodolfo C. Severino, in The Philippines’ Foreign Relations: Threats and Opportunities published by ISEAS, 2003 argues: To begin substantive negotiations on Philippine territorial or maritime disputes or overlapping EEZs is to determine the extent of the territorial sea. 3 Justice Jorge R. Coquia records that, except for Tonga, no state agreed to the Philippine claim of territorial waters based on the Treaty of Paris when it was referred to by the Philippine delegation at the First UN Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1958. 4 Significantly different in meaning from the term “maritime law” is the conceptual framework law of the sea. Maritime law deals with jurisprudence that governs ships and shipping whereas the latter refers to matters of public international law, including the definition of a state’s territorial waters. The territorial sea differs from the internal waters in that the former is subject to an international right of innocent passage at least in time of peace. The legal status of territorial sea also extends to the seabed and subsoil under them and to the airspace above them. Ownership of petroleum in situ has to be determined. The Convention provides the legal basis for undertaking offshore petroleum operations beyond the territorial waters of a coastal State. Considerations: The different sea areas claimed by the Philippines in exercise of its sovereignty as an archipelagic State have their respective juridical status under international law. As such, they are subject to a particular international regime discussed in succeeding pages. 3. Concept of Archipelago The convention of the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone has described an island as “a naturally-formed area of land, surrounded by water, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide.” Article 121 of UNCLOS adopts this description of an “island”. In relation to every nation, if politically independent (or otherwise), it can be categorized as shown in the Table below. Table 1 - Category of Islands Islands are coastal States in their own right e.g. United Kingdom, Cuba, Sri Lanka Islands fall under jurisdiction of a coastal e.g. Corsica, the Falklands, State Andaman islands Islands form an archipelagic State e.g. Indonesia, Philippines, Fiji islands Contemporary publicists on international law categorize the types of archipelagoes into: (1) Coastal archipelagoes – situated so close to a mainland that they may reasonably be considered part and parcel thereof. Thus, they form more or less an outer coastline from which it is natural to measure the marginal seas. 5 (2) Outlying or mid-ocean archipelagoes – groups of islands situated out in the ocean at such a distance from the coasts of firm land. Thus, they are considered as an independent whole rather than forming part of the outer coastline of the mainland. Considerations: The coastal States may be subdivided into those bordering the enclosed or semi-enclosed seas and coastal states bordering the oceans. At UNCLOS negotiation, the nonresource side of maritime jurisdiction is addressed by the coastal States and the archipelagic States such as rules and regulations relating to innocent passage and passage in transit. 4. The Philippine Territory The geographical configuration of the Philippine archipelago constitutes a massif or compact formation and a group of islands situated between latitudes 5 and 21, and between longitudes 117 and 127 degrees. This geographical formation is fringed all along by a string of islands and islets of varying sizes and shapes that follow a general direction and form a continuous row of land formations. The latitudes and longitudes described in Article III of the 1898 Treaty of Paris between Spain and the United States and the 1900Treaty concluded at Washington D.C. between the two countries required another Treaty in 1930 between Great Britain and the United States to fix the boundary lines between North Borneo and the Philippine Archipelago. Table 2 - Geographical Data about Territory Land area of the Philippines is 115,600 square (statute) miles 87,278 square nautical miles Philippine territory described by the International Treaty Limits 520,700 square nautical miles Philippine total baselines area defined under Republic Act 5446 plus enclosed territorial sea 257,400 square nautical miles Philippine policy based on UNCLOS covering maritime area up to the 200-mile EEZ 652,800 square nautical miles The use of the Treaty Limits as the territorial sea boundary would raise the total Philippine area to 702,460 square .miles or 530,239 square nautical miles. 6 As between two competing ideas of retention or elimination of the National Territory provision, a constitutional delineation appears necessary for reasons of jurisdiction over territorial waters. Considered as “necessary appurtenances” 4 of its land territory, all sea pertaining to the Philippine Archipelago as delimited by municipal Act and enabling laws are divided into types of waters: 5 (1) national or internal waters embrace all the sea areas lying between and connecting the constituent islands, islets and other land formations of the archipelago, irrespective of their width or dimension; (2) marginal belt of water, in addition to its national waters, surrounding the coast of the archipelago viewed as a whole or as a unit in law; (3) contiguous zones assimilated to territorial or jurisdictional waters for certain special purposes, and measured from the outer edge of the marginal belt up to the treaty limits; and (4) superjacent waters of the “continental shelf” or its analogue in an archipelago extending seaward from the shores but outside the area of the territories of other countries. The Philippine Fisheries Code of 1998 Sec. 64. Philippine waters – include all bodies of water within the Philippine territory such as lakes, rivers, streams, creeks, brooks, ponds, swamps, lagoons, gulfs, bays and seas and other bodies of water now existing or which may hereafter exist in the provinces, cities, municipalities, and barangays and athe waters around, between and connecting the islands of the archipelago regardless of their breath and dimensions, the territorial sea, the sea bed, the insular shelves, and all other waters over which the Philippines has sovereignty and jurisdiction including the 200-nautical miles Exclusive Economic Zone and the continental shelf. Considerations: An important point at this juncture is that no difficulty confronts the juridical status for most of the superjacent waters of its island shelf that lie inside the archipelago and accordingly are assimilated into internal waters. Those portions situated along the outer limits of the archipelago and which extend seawards belong either to the regime of the territorial sea or to that of the contiguous zone. 4 This phrase appears in the Philippine Mission’s Note Verbale of March 7th, 1955. For the full text, consult Yearbook of the Internal Law Commission, 1956, Vol. II, p. 70. 5 The “sea areas” classified into types of waters became the basis of the new definition of national territory and the validity of the position at the Conference on the Law of the Sea. Ambassador Juan M. Arreglado submitted a study dealing with the geographical and juridical delimitation of the extent of its territorial waters to the 1972 Constitutional Convention. The Philippine delegation to the 1958 Conference on the Law of the Sea composed of Senator Tolentino as chairman and Jorge Bocobo and Arreglado as members. 7 5. The Philippine Baselines There are normal baselines and straight baselines to define the archipelagic regime of the territorial sea. Article 5 of the Convention says that the normal base line for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea is the low-water line along the coast. All waters within the normal baselines as provided for marked on large-scale charts are considered inland or internal waters of the Philippines. The Government of the Philippines with respect to its land domain, archipelagic sea lane passage, and inter-island waters with surrounding land has adopted the archipelagic method joining appropriate points, in drawing a series of straight baselines about the external group from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured. The Philippine system of straight baselines 6 for its territorial sea are defined and described in R.A. 3046 of 1961, as amended by R.A. 5446 of 1968, to correct typographical errors. 7 Following the archipelagic doctrines, the new baselines proposed in 1987 diverts from the maritime territorial boundaries defined under the Treaty Limits. This became necessary to qualify the bases of the Philippine claim to the cluster of islands and islets in the South China Sea as part of the Philippine territory. This trend towards extended national jurisdiction is but one aspect of the strategic drive to assume control over natural resources. Not only the economic argument but strategic considerations apply: (1) The emerging law of the sea regime is closely tied to regime change including the application of the archipelagic state regime, the twelve-mile territorial sea, the twenty-four-mile contiguous zone, the 200-mile exclusive economic zone, the continental shelf, and the other jurisdictions with regard to marine environment and scientific research. (2) The emergence of the concept of the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) has helped to determine the juridical regime in regard to the extent of coastal State and 6 This municipal Act was protested by US Embassy Note No. 836 of May 18, 1961 declaring inter alia … the United States Government could not regard claims based on the present legislation as binding upon it or its nationals.” 7 The principal sponsor was Senator Arturo M. Tolentino. In 1987, Senator Leticia Ramos Shahani sponsored a bill (S. No. 206) to redefine the straight archipelagic baseline but it was not passed during the Eight Congress. The definition of the baselines of the the territorial sea of the Philippine Archipelago as provided in R.A. No. 5446 is “without prejudice to the delineation of the baselines of the territorial sea around the territory of Sabah, situated in North Borneo, over which the Republic of the Philippines has acquired dominion and sovereignty” (Sec. 2). Thus, Congressman Michael O. Mastura introduced H. No. 4428 to repeal any reference to delineation on Sabah under Section 2 of R.A. 5446 to read: “Philippine negotiating text on boundary delimitations under the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention”. 8 archipelagic State competence landward side of the baseline as well as seaward from which the breath of the territorial sea is measured. 6. Regime of the Archipelagic State The enclosed seas of the Philippines, including the Sulu Sea, appear as basin seas within the submarine platform that connects Mindanao to rest of the constituent islands, separated by shallow barriers or submarine ridges from the Pacific Ocean to the East, from the South China Sea to the West, and from the Indonesian Seas to the South. The bottom water of the central seas of the Philippines is not in free communication with that of any of the above-mentioned seas and ocean. According to an international boundary study on limits in the seas, 8 the Philippine straight baseline system in effect: • Adopts a method of measurement within its archipelagic waters in drawing a series of 80 straight baselines about the external group and outermost points. • Closes the important Surigao Strait, Sibutu Passage, Balabac Strait and Mindoro Strait as well as the more internal passages through the Philippine islands. • Encloses the largest body of water, the Sulu Sea, but other significant seas, the Moro Gulf, Mindanao Sea, Sibuyan etc. are also within the system. In summary, the enclosure system therefore increases the national “territory” approximately 2.8 fold. Application of the archipelagic regime extends the territorial sea and the resulting land to water ratio is approximately 1:1,841. Figure 1 - Land Area to Territorial Waters Ratio Straight Baseline of the Philippines The method of baseline system can be illustrated by area figures and ratios: Land Area 115,600 square miles Water Space 328,345 square miles Say: 328,345 - 115,600 = 212,745 square miles or 1:1,841 The use of the Treaty Limits as the territorial sea boundary would raise the total Philippine area to 702,460 square miles or 530,239 square nautical miles. This approach increases by more than 2.14 the “territory” within the baselines. 8 Data culled from an analysis of the Philippine straight baselines in International Boundary Study, Series A, Limits in the Seas, No. 33 (March 22, 1973. 9 Figure 2 - Land and Internal Waters to Territorial Sea Treaty Limits of the Philippines The use of the treaty limits can be illustrated by area figures and ratios: Land Area 702,460 square miles Territorial Sea 374,115 square miles Ratio of Land and Internal Waters to Territorial Sea is 1: 1,139 Ratio of Land to Territorial and Internal Waters is approximately 1:5,065 Considerations: As much as the principles for arrangements of rights and interests of coastal State have been acceptable but outstanding delimitation negotiations could be carried out where they constitute prejudicial question on the status of the Bangsamoro homeland and ancestral domain. The Bangsamoro people’s claim is founded on historic rights and native title and other special circumstances; it is consistent with UNCLOS. 7. Outstanding Negotiation Issues The breadth of the territorial sea—hence, the seaward extent of the territorial sovereignty of the coastal State or archipelagic State—is now internationally agreed. 7.1. Extension of Sovereign Authority and Jurisdiction The doctrine leading to the theory that the seaward limits of territorial sovereignty should coincide with and could not exceed the range of shore-based cannon is practically abandoned in favor of a twelve-mile limit. The three nautical miles range was originally based on one league that international law set as the width of territorial waters. Beyond the seaward limits is the domain of the high seas. The principle of freedom of the seas respects the right to navigate, to fish, to lay cables and pipelines, and the freedom of overflight. Now it is recognized that coastal State has jurisdictional right to regulate, police, and adjudicate the territorial waters and the proprietary right to control and exploit natural resources in those waters and exclude others from them. The legal status of territorial waters also extends to the seabed and subsoil under them and to the airspace above them. Attention has always been focused on the superjacent waters and on the commercial use that could be made of these waters. In practice, it amounts to navigation and fishing. So the question of where the jurisdiction lay over the natural resources underneath the high seas had to be solved before industry could move into the domain. 10 Table 3 – Determination of Expanded Jurisdiction Area of the Philippines including 3 mile territorial sea about each island is 115,600 square nautical miles. Whether EEZ would be outside both its archipelagic waters and its territorial sea but falls within the Treaty Limits? Area of the Philippines with 12 miles territorial sea about each island is 178,000 square nautical miles. Whether different boundaries of EEZ would be taken as the same boundaries of the Contiguous Zone? Area of the Philippines enclosed in Baselines plus 12-mile territorial sea from Baselines is 290,850 square nautical miles. Whether different boundaries of EEZ have to be determined by agreement with neighboring adjacent coastal State 7.2. The Prolongation Argument In 1945, America preempted unilaterally to claim the sovereignty over the resources of the subsoil and the seabed of the continental shelf beneath the high seas but contiguous to the coast of the US. Its proclamation restricts the natural resources jurisdiction of the US to its continental shelf. The prolongation argument holds that the continental shelf should be regarded as an extension of the land mass of the coastal State and thus naturally appurtenant to it. Notably this carries enough weight to support and justify the proclaimed jurisdiction. I.C.J. upheld it in the North Sea Continent Shelf cases (1969). The 1958 Convention assigns any island a continent shelf. It assigns sovereign rights over it to coastal State, but not to islands. What regime is to be applied to the seabed and subsoil or the resources contained therein beyond the twelve-miles? The limit of the seaward boundary of the continental shelf includes the same seabed and subsoil beyond the 12-mile territorial sea up to the distance of 200 miles from the baselines or up to the outer edge of the ocean margins. The Philippine negotiating position at UNCLOS reiterates the “necessary appurtenances” of its submarine platform and land formations. Noticeably Article 1 of the 1987 Constitution now mentions the “insular shelves” and other submarine areas, 11 besides the seabed and the subsoil. 9 The MILF position is open to production sharing agreement or joint development pact in terms of the environmental aspects and the internationalization of the extractive industry. Negotiation Pointers: National regulatory regimes for petroleum may be categorized by the type of authorization that is provided for. Authorizations take the form of either a license or a contract of work. The manner in which the rights attached to a license or a contract area are described in the basic petroleum law. A government with a production sharing system does not grant a concession. Authorization matrix: Ownership of petroleum in situ conditions vests in the State Petroleum as occurring under natural on the surface or in the subsoil Ownership of petroleum after extraction from the reservoir Production license or contract confers ownership on the holder per terms and conditions The Petroleum Act of 1949 contained the clause, “whether found in, on or under the surface of dry lands, creeks, rivers, lakes, or other submerged lands within the territorial waters”. The licensing regime was in essence a property law extending the ownership of land to the mineral resources. Such property right mineral acquisition rights could be obtained from the public or private owner of the land concerned. The case of wetlands—such as the Liguasan marshland of almost 45,000 hectares purported to hold significant deposits the ownership of petroleum—could be tied to their disposition. From the point of legal theory, the migratory character of liquid and gaseous petroleum was correctly posed as a problem on the nature of the ownership of petroleum. In so far as relevant for the interpretation of the Petroleum Act of 1949, as amended, geologically speaking, the Philippine mission to the First Conference on the Law of the Sea enunciated its position based on the Note Verbale of March 7, 1955 to the UN Secretary General. 9 Proclamation No. 370, 1968 declares as subjection to the jurisdiction and control of the State all mineral and other natural resources in the continental shelf of the Philippines. Extended jurisdiction covers the areas of seabed mining and off-shore petroleum. 12 Note Verbale 1955 All natural deposits or occurences of petroleum or natural gas in public and/or private lands (or other submerged lands) within the territorial waters or on the continental shelf, or its analogue in an archipelago, from the shores of the Philippines which are not within the territories of other countries belong inalienably and imprescriptively to the Philippines, subject to the right of innocent passage of ships of friendly foreign States over these waters. The Proclamation of March 20, 1968 has substantially modernized it where the continental shelf is shared with an adjacent state. In this case the boundary shall be determined by the Philippines and that state in accordance with “legal and equitable principles.” It is declared the character of the waters above these submarine areas as high seas and that of the airspace above those waters is not affected by this proclamation. Prospecting/ Extracting from Reservoir Petroleum – a mixture of liquids and gases is a natural resource that is not fixed at the place of its generation, unlike other mineral resources that fixed at their place at the surface or in the subsoil. After generation petroleum migrates and moves through the porous and permeable rock layers of the subsoil. . As a matter of fact the production operation can be said to start a secondary migration. As soon as wells are drilled from the surface into a reservoir the petroleum starts flowing into these wells and through the tubing inside the wells up to the wellhead at the surface or at the bottom of the sea, as the case may be. The oil/water separation is critical. The oil/gas separation can be described as the first stage of the refining process. Source: Petroleum, Industry and Governments, 1999 The Convention sets the basic conditions of prospecting, exploration and exploitation (see Annex) for specified categories of resources in the area covered by a plan of work. Question: What is the implication of the new extensions of coastal State sovereignty once EEZ is added to those of the continental shelf and the archipelagic waters? The key is in understanding first the notion of continental shelf. It refers to the seabed area beyond the territorial sea to the superjacent waters. Does the “insular shelf” lie outside both the territorial sea and archipelagic waters? For the Philippines, on the side facing the Pacific, there is an immediate ocean deep in Mindanao. 13 In the Philippines, geologically speaking, similar to Indonesia some of the seabed under its archipelagic waters or territorial sea may fall within the meaning of continental shelf. Therefore, legally speaking, the Philippines does not consider it as part of the regime of continental shelf but as part of the regime of archipelagic waters or territorial sea. 7.2. Equidistance and the Middle-Line Argument The archipelagic State as sovereign entity is self-determined to assert the surface boundary line issue in the management of marine resources. In regard to extended fishery jurisdiction out to 200 miles from the shore the new framework of coastal fishery management has replaced the traditional fishery regimes. In the long run, it is better to protect and secure the entire stock within coastal waters than to depend on the catch from distant water fishery. Jurisdictional/ boundary disputes in the South China Sea or the Sulu Sea or Mindanao Sea do not have its roots in fishery matters. The marine boundary delimitation is a separate nonresource issue from marine fisheries and open access to living resources. Marine resources are transboundary in nature. The migratory pattern of species is of relevance to fisheries jurisdiction in a regional setting here. Negotiation Pointers: Acceptance of the concept of the exclusive economic zone does not lessen the need for cooperation for management of resources. Preferential use based on Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) or Total Allowable Catch (TAC) aims to protect the rights of fisherfolk. Demarcation Matrix of Fishery Rights: Traditional fishery rights in territorial waters and certain areas of the archipelagic waters or near-shores Any reference to “traditional fishing rights” applies to the fishermen themselves, their equipment, their catch, and their fishing grounds or area to waters which the waters rights and activities are applied. Fishery management regime of distant water fishermen/ fleet or commercial fisheries Joint marine resource management of the coast for developing fishing industry and fishery reserve, refuge, and sanctuaries The Fisheries Code of the Philippines under Section 80 provides fishery reserves and sanctuaries in Philippine waters. An area or areas beyond fifteen (15) kilometers from shoreline may be designated for the exclusive use of the government or any of its political subdivisions, agencies or instrumentalities, for propagation, educational, research and scientific purposes. The MILF position is the application of the archipelagic State regime such that the governing principle is land and sea cannot be separated as part of the same ecological system. 14 Coastal Façade Theory Apart from the concerns of proportionality for island-countries facing continental land masses and the littoral states, another point is the configuration of most semi-enclosed seas in the operation of distant-water fishing. In effect the extension of zones of economic jurisdiction of the Philippines and the adjacent countries to 200 miles could leave no high seas area within the semi-enclosed sea (South China Sea) and enclosed sea (Sulu Sea). Property rights, then, once established, will set the stage for resources management and environmental purposes. The delimitation of the continental shelf boundary differs from the EEZ, which is for the water column, in concepts and outer limits. In fact, the actual lines of delimitation between opposite and adjacent neighboring States can also be different correspondingly. The point here is that the median-line argument does not always seem the last resort when the principle of equidistance renders inequitable divide. Juridical Status and Ocean Regime Extensions of coastal sovereignty and jurisdiction at Sea include application of: - Archipelagic state regime - Twelve-mile (12) territorial sea - Twenty-four (24) contiguous zone - Two hundred-mile exclusive economic zone - Continental shelf (up to edge of ocean margins) Various jurisdictions on marine environment, and management of marine resources. Geographical discrepancy among ASEAN member countries deters them from establishing permanent exclusive fishing zone and to delimit the respective EEZ boundaries. North Borneo is only 18 miles away from the nearest island of the Sulu archipelago. Since the continental shelf regime on which Malaysia rests its claim to part of the Spratlys begins from the coast of Sabah, the sovereignty-based Philippine claim has become less pronounced as thematic continuity. 7.3. The Historic Title Argument As shown in the previous section, there exists prejudicial error and technical discrepancy between the baselines and the treaty limits demarcation lines. The National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA) explains that by signing and ratifying the UNCLOS the Philippines stands to lose some waters that were defined 15 within the Treaty of Paris. But it means also acquiring some parts of the ocean that were not within the limits of the National Territory before. Negotiation Pointers: A number of factors in the evolution of the archipelagic State have important bearing on the territory of the Bangsamoro juridical entity. First, there are legal factors. The term “archipelago” is defined for the purposes of the Convention. It means a group of islands closely interrelated or which “historically have been regarded as such”. The MILF ancestral domain claim is in keeping with this argument based on shared or earned sovereignty. Of course it has bearing on customs, immigration, and quarantine (CIQ) regulatory regime. UNCLOS, Paragraph 4 of Article 49 The regime of archipelagic sea lanes passage established in the Part shall not in other respects affect the status of the archipelagic waters, including the sea lanes, or the exercise by the archipelagic state of its sovereignty over such waters and their air space, bed and subsoils, and the resources contained there. As incident to the legal status of archipelagic waters, it binds the islands, waters, and other natural features of the Philippines as an “intrinsic geographical economic and political entity” or which “historically have been regarded as such”. Anticipations of diplomatic sensitivity to pressing issues that impinge on the island-country’s overlapping maritime areas with Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam is important to encourage regional cooperative arrangements for the Bangsamoro juridical entity. Second, there are unsettled territorial disputes. Aside from the Sabah claim, the Spratleys dispute has had little significance to the previous framework of peace agreement between GRP and MNLF. This can explain why in the current GRP and MILF peace talks the negotiations cover ancestral land domain, territorial waters and natural resources. The influence of power politics in establishing ocean regime is not new to the Bangsamoro as a maritime people. Current law-of-the-sea diplomacy and politics can make the envisioned Bangsamoro juridical entity regain naturally and survive incrementally the “grabbing game” of ocean resources. Third, there are tangible natural features. Along the southern Treaty boundary of the Sulu Sea delimiting the maritime frontier between the Philippines and North Borneo, it is dotted by rocky islets and shoal patches which reduce the navigable channels. The waters of Sulu Sea do not envelope nor touch the coast of any other littoral State. It covers a total area of 85,000 square miles and accentuates the most prominent feature of the archipelagic State with a sea lane passage. 16 Enclosed or Semi-enclosed Sea Article 122 defines an “enclosed or semi-enclosed sea” as a gulf, basin, or sea surrounded by two or more states and connected to the open seas by a narrow outlet or consisting entirely or primarily of the territorial seas and exclusive economic zones of two or more coastal States. This provision does not deal with the issue of delimitation or the question of the freedom of navigation in these maritime areas. On this matter, the Convention does not create a special regime for those zones. So it avoids imposing, under Article 123, the cooperation of maritime nations bordering enclosed or semi-enclosed seas. The MILF believes that is at the basis of a “historic right” to marine resources in the Sulu Sea, Moro Gulf, and Mindanao Sea areas. Given finally the attention to the law of the sea regime, the foundation for Philippine national arrangement runs counter to the Indonesian straight baselines in the southeast extreme facing the Pacific Ocean. The Indonesian island of Pulau Miangas is contained within the Philippine territorial sea and the Indonesian straight baselines. Within the meaning of Article 123, it could be also the external and internal aspects of the common fisheries policy or common border joint patrol. Conclusion One does not expect sovereignty to remain unaffected to organize contemporary reality into two distinct spheres of the domestic and the international. The Government has to reassess the constitutional implications of its involvement in negotiations concerning either sovereign rights or joint use and exploitation of resources, for example, in the Spratleys (See CIRSS Papers, 1993, Foreign Service Institute). The bases of title and the claims of sovereignty rights are increasingly blurred or indistinct based on concepts evolved gradually in the law of the sea regime. Because the matter of the extension of coastal sovereignty and jurisdiction at sea was “the weightiest consideration” leading to the decision of the Government to sign the UNCLOS, it has anchored its archipelagic doctrine on the unique nature and configuration of the territorial sea. The Bangsamoro juridical entity’s geographical significance lies in the fact that it consists of two different components: the mainland Mindanao eastern part characterized by its land domain element; and the maritime domain western part waters element of which the Sulu sea areas largely prevails, together with the Moro Gulf and the Mindanao Sea. 17 N. B. The MILF proposed text was submitted in separate pages to be reconciled with the GRP proposed text. The working drafts are reduced into the Agreed Text, which will then be incorporated into the provisions of the Matrix on the Strands of Ancestral Domain. The Agreed Texts together with the maps to depict the demarcations and boundary lines form substantive parts of the Memorandum of Agreement on the Ancestral Domain Aspect covering the four Strands: Concepts, Territory, Resources, and Governance. Paper prepared for the MILF-GRP Exploratory Talks (Kuala Lumpur, November 2007). The comments of lawyers Ishak V. Mastura, Musib M. Buat and Lanang Ali have been incorporated into the discussion. 18 Appendix Archipelagic Status 10 Understand knowledgeable management of all the resources of the archipelago Insure sovereignty and international rights Influence power politics in establishing ocean regime Governing principle: Land and sea cannot be separated being both part of the same ecological system. This fundamental principle of unity of land and sea should guide us in formulating the law of the sea. Commercial and strategic (long-range) importance: - Jurisdiction for managing the oceans waters and seabed surrounding any island-state must vest in the people who inhabit that state. Due consideration must be given to traditional rights and duties, constitutional provisions, international law and treaties. Issue: Oceanic/ mid-ocean archipelagos are unique – separated from other states and peoples by vast expanses of international waters. For example, Hawaii is an oceanic archipelago. • • • Open access for deep seabed Management of migratory species Protection of maritime heritage Sea turtle lays its eggs in a federal (national), migrates into state waters on state reefs, then, proceed into the 200-mile EEZ, having pass through waters of uncertain jurisdiction. They migrate into international waters and journey in islands of disputed jurisdiction. Laws of protection change. Each island country has an exclusive economic zone with: ¾ a potential for fishing and for maricultre ¾ a potential for ocean thermal energy development ¾ a long-range potential for a visitor destination There are concerns for limitation of access to the economic zone and the economic resources of the archipelago regardless of the complexities of jurisdiction and sovereignty. This is all about the common heritage provisions. Measure: Delimitation of EEZ (Art 74) and of Continental shelf (Art 83) boundaries, although the principles adopted are similar, if not the same. 10 This is part of the Research Paper for Category “C” prepared by lawyer Michael O. Mastura for the MILF-GRP Exploratory Talk on Territorial Waters (Category “C”). November 8, 2007 19 Issue: Whether the existing continental shelf boundaries could be taken as the boundaries of the EEZ as well. Or, would a new set of boundaries for EEZ have to be negotiated? The Philippines and Indonesia are an outlaying / off-laying archipelagoes. • • Limit of the continental shelf - 200 miles or the outer edge margins Limit of the EEZ - 200 miles Issue: Whether the actual lines of delimitation between opposite and adjacent states would be different? The boundary of the continental shelf often deviates from the normal median line for various reasons. But the reasons to deviate from the median line would be much less for the delimitation of the EEZ. UNCLOS has separate articles to deal with the issues for each regime. This implies the possibility for of different delimitation of boundary lines of the EEZ and the continental shelf, territorial sea and contiguous zone. Confront the problems of implementing the archipelagic principles - Application of archipelagic principles to exclude the use of archipelagic waters for dumping oil and other wastes and enable the government to protect the environment from harm. - Application of archipelagic principles for defense and security and law enforcement and enable the government to protect the safety, stability, and interest of the country. Question: What is the implication of the new extensions of coastal State sovereignty once EEZ is added to those of the continental shelf and the archipelagic waters? Understand first the notion of continental shelf. It refers to the seabed area beyond the territorial sea to the superjacent waters. Does the “insular shelf” lie outside both the territorial sea and archipelagic waters? For the Philippines, on the side facing the Pacific, there is an immediate ocean deep in Mindanao. In the Philippines, like Indonesia, geologically speaking, some of the seabed under its archipelagic waters or territorial sea may fall within the meaning of continental shelf. Therefore, legally speaking, the Philippines does not consider it as part of the regime of continental shelf but as part of the regime of archipelagic waters or territorial sea. And so, the country has full territorial sovereignty over the areas rather than merely sovereign rights to the exploration and exploitation of resources. 20 The delimitation issues remain unresolved with respect to: - the Celebes with Indonesia the South China Sea with Malaysia, Vietnam, and China the mutual margin with Malaysia and Indonesia The Petroleum Act of 1949, as amended, is practically similar to the American legal system that takes into account and recognizes the special physical characteristics of a mineral resource consisting of a mixture of liquid and gaseous substances. In fact this legal system was no more than extending the ownership of land to the mineral resources on or beneath the land. As such, “the property right mineral acquisition rights” could be obtained from the public or private owner of the land. Question: What if the mineral and other natural resources are located in the continental shelf adjacent to the Philippines is shared with an adjacent state? The boundaries have to be determined by the Philippines and that country in accordance with legal and equitable principles. The character of the waters above these submarine areas as high seas and that of the airspace above those waters is not affected according to Presidential Decree No. 370 dated March 20, 1968. Know the determination of the legal regime - Establish own EEZ outside its territorial sea around the Philippine archipelago Note: For the Philippines, the EEZ is outside both its archipelagic waters and its territorial sea. The regime will follow as much as possible the text of the Convention. Presidential Decree No. 1599 dated June 11, 1978 establishes an EEZ. By this, it extends to a distance of 200 nautical miles beyond and from the baselines from which the territorial sea is measured. Where the outer limits of the zone as thus determined overlap the EEZ of an adjacent or neighboring state, the common boundaries is to be determined by agreement with the state concerned or in accordance with principles of international law on delimitation. The expression in the decree “without prejudice to rights over its territorial sea and continental shelf” is a caveat to the exercise of sovereign rights for purposes of exploration and exploitation, conservation and management of the natural resources of the seabed, subsoil and the superjacent waters (i.e. from production of energy from the water, currents and winds). 21 Area of the Philippines including 3 mile territorial sea about each island is 115,600 square nautical miles. Area of the Philippines with 12 miles territorial sea about square nautical miles. each island is 178,000 Area of the Philippines enclosed in Baselines plus 12-mile territorial sea Baselines is 290,850 square nautical miles. from - Manage own EEZ and marine environment coordinated with management of the archipelagic waters The legal regimes of the two areas are different yet they are interrelated, and so in physical fact would form an integrated ecosystem. Note: The Philippines has declared its EEZ under P.D. 1599 and its basic petroleum zone under Proclamation No. 370. 22