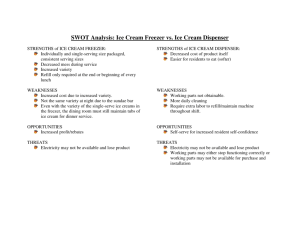

2015-Feb-marketing_c..

advertisement