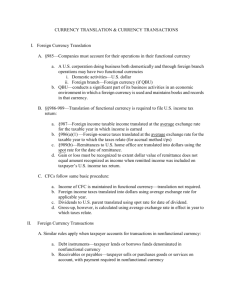

Overview of the Taxation of Foreign Currency

advertisement