Journal of Stevenson Studies Volume 9

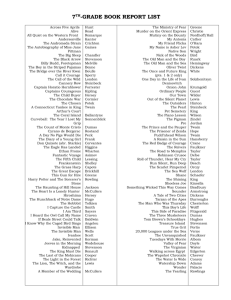

advertisement