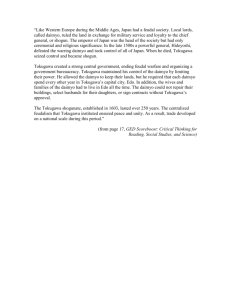

Lordly Pageantry: The Daimyo Procession and Political Authority

advertisement