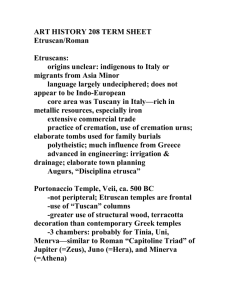

The Roman Empire

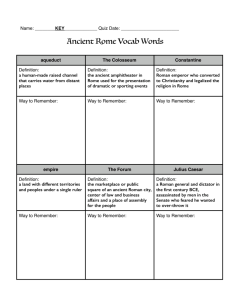

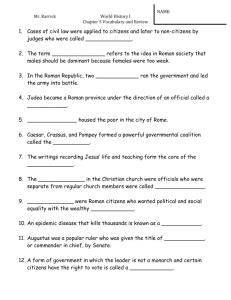

advertisement