Knowledge Transfer in Global Product Development at Volvo Buses

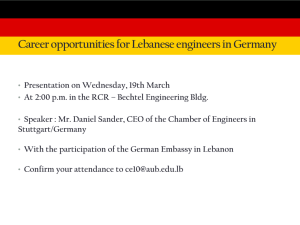

advertisement