Understanding Human Resource Challenges in the

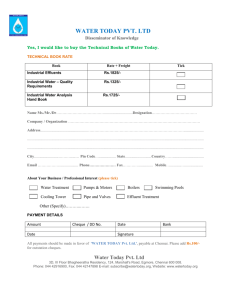

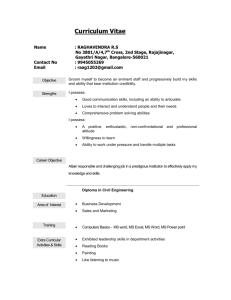

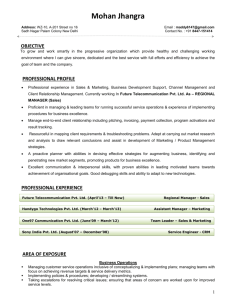

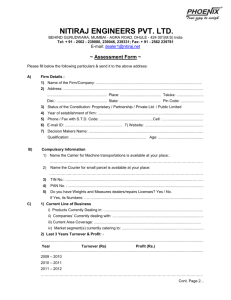

advertisement