Information and trust in financial decision making

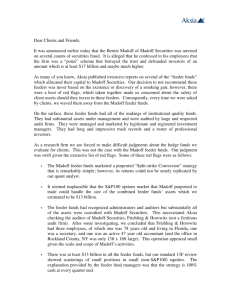

advertisement