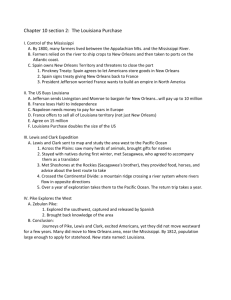

an ethnic geography - Richard Campanella

advertisement