Leviticus - Virginia Theological Seminary

advertisement

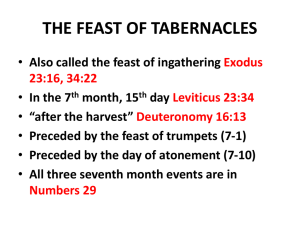

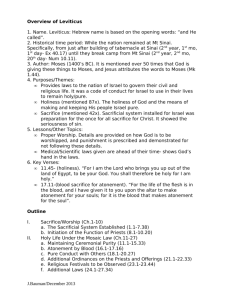

LEVITICUS Kevin A. Wilson Leviticus stands at the heart of the Torah. It falls between the salvation of Israel out of Egypt in the book of Exodus and the journey to the promised land in Numbers. In Leviticus, God gives those laws that will govern the lives of the people of Israel as they seek to live as a community with God in their midst. It contains the ordination of the first priests, the institution of the sacrificial system, and numerous concepts and precepts that are central to what it meant to be the people of God in ancient Israel. And nestled among these laws is one Jesus listed as the second most important commandment: “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Leviticus 19:18; cf. Matthew 22:39; Mark 12:31; Luke 10:27). But despite its centrality and importance, Leviticus also remains one of the most neglected books of the Bible among Christians. It is rarely read for devotional study and is only infrequently—if ever—the subject of church 2 Bible studies. Leviticus does not fare much better in the church’s worship. Both the lectionary in the 1979 Book of Common Prayer and the Revised Common Lectionary assign Sunday readings from Leviticus only two times in the three year cycle, and in both instances the reading is optional. Some of the neglect of Leviticus can be traced to the complexity and seeming irrelevance of the book. Leviticus focuses on minutiae such as which parts of the animal should be burned on the altar and which parts should be burned outside the tabernacle (Leviticus 1–7). It goes on for two whole chapters on the subject of skin diseases (Leviticus 13– 14). And it deals with economic laws that seem out of touch with modern ways of doing business (Leviticus 25). Understanding these laws is necessary, however, if one wants to understand the rest of the Bible. The sacrificial system instituted in Leviticus is the basis for sacrifices throughout the Old Testament and was still in place during the life of 3 Jesus. The passages on skin diseases form the backdrop to the story of Jesus and the healing of the lepers (Matthew 8:1-4; Mark 1:40-45; Luke 5:12-16), while the economic justice envisioned by Leviticus 25 is seen by Luke as fulfilled in the ministry of Christ (Luke 4:18-19). It is fair to say that without an understanding of Leviticus, our understanding of the rest of the Bible is incomplete. But not all of the neglect of Leviticus can be blamed on the book itself. Some of the blame falls on our own distaste of anything that smacks of legalism. Since the mid-nineteenth century, it has been common to view the religion of the Hebrew Bible as an originally lively faith, with an apex in the preaching of the prophets, that later devolved into a dead, legalistic religion, as seen in the priestly material of the Pentateuch. Such a view owes much to the New Testament’s criticism of the priests in Jesus’ time, but Protestant churches have often carried this idea to 4 the extreme in the wake of the Reformation. Anything that appears hierarchical and legalistic seems suspect to us, and Leviticus certainly falls in that category. Fortunately, in the last few decades this negativity towards texts from priestly circles in the Old Testament has begun to be tempered by a more positive evaluation. Instead of dating all priestly material to the postexilic period and viewing it as a calcified form of an earlier, more vital religion, scholars have begun to recognize that a good deal of the priestly material comes from the preexilic period. Far from being a dead legalism, the priestly theology— including that in Leviticus—was a lifegiving tradition that existed alongside the prophets and complimented their work. In fact, some of the prophets, such as Isaiah and Ezekiel, drew heavily on the priestly traditions to address the religious and social issues of their time. Like these prophets, the modern church needs to learn to appropriate the rich 5 theological heritage of ancient Israel’s priesthood for our modern life as the community of God. The Origins of Leviticus The Pentateuch is a composite document. Unlike modern books, which are written by one author, the Torah developed over time. Different theological streams of thought came together to form the first five books of the Bible. Genesis, Exodus, and Numbers are a mixture of priestly and non-priestly material. The non-priestly material is often referred to as the Yahwist (J), due to its use of the divine name Yahweh (German: “Jahweh”) prior to its revelation to Moses on Mount Sinai. The book of Deuteronomy (D), on the other hand, stands apart from Genesis– Numbers, having been written by authors who were a part of neither the priestly nor the Yahwistic schools. In the postexilic period, these three strands 6 were combined into the Pentateuch as we have it today. The priestly material in the Torah does not all come from the same time period. One set of traditions—often called the Priestly Torah (PT)—arose in the preexilic period. These traditions were the official theology of certain temple priests in Jerusalem. The second set of traditions reached their final form in the period after the Babylonian exile (597–538 B.C.E.). These texts are a product of a group of priests that have been labeled the Holiness School (HS). In addition to contributing their own material to the Torah, it is likely that the Holiness School was responsible for combining J, PT, and D to create the Pentateuch in its canonical form. The book of Leviticus is the only book in the Torah made up solely of priestly material. The extended account of Israel’s year-long sojourn at Mount Sinai running from Exodus 19 to Numbers 10 contains some material from J, but none of it is found in 7 Leviticus. Leviticus is entirely of priestly origin, including traditions from both PT (predominant in Leviticus 1–16) and HS (predominant in Leviticus 17–27). This is not to say, however, that material in Leviticus pertains only to priests. This misconception dates back to the Greek translation of the Old Testament, which gave the title Leutikon to the book because it thought the text applied primarily to the priests, i.e., the Levites. It is from that Greek tradition that we get the English title Leviticus. But the Hebrew name for the book is wayyiqrä´, which is taken from the first words of the book: “And God called (to Moses).” God called to Moses in order to deliver the law to him for passing on to the people. While Leviticus does contain material of importance to the priests, the priesthood is never seen in isolation from the people. For example, Leviticus 1–7 contains instructions for how the priests are to officiate in sacrificial rites, but the people of Israel are the ones who are to 8 bring the sacrifices. They have as big a role—if not bigger!—in bringing their offerings to God. Structure and Setting Leviticus can be divided into four sections. The book opens with a manual of sacrifice in chapters 1–7. Here we find instructions for the five major types of sacrifices in ancient Israel: the burnt offering, the grain offering, the offering of well-being, the sin offering, and the guilt offering. This is followed by the only narrative section of the book, the ordination of Aaron and his sons as priests in Leviticus 8–10. Next come chapters containing laws for maintaining purity (chapters 11–16). The concluding section, known as the Holiness Code (chapters 17–27), provides instructions for living as holy people so that God may dwell in their midst. With the exception of chapters 8– 10, Leviticus contains no narrative 9 sections, yet it is integrally connected to the narrative logic of the book of Exodus. Exodus begins with the people of Israel in Egypt, and through the first half of the book God works to deliver them from slavery. Once freed, they are led to Mount Sinai where God makes a covenant with them: Israel will be the people of Yahweh, and Yahweh will be their God (Exodus 6:6-8, 19:3-6). After making the covenant, God gives Moses instructions for the building of the tabernacle (Exodus 26–31), the movable shrine that will serve as the place of worship in the wilderness. The people of God make the tabernacle according to the plans provided (Exodus 35–40) and God takes up residence in the tabernacle (Exodus 40:34-38). This leads directly into the book of Leviticus, which is set up as instructions given by God from inside the tabernacle. Now that God has begun to dwell in the midst of the people, the people can begin to bring offerings to God. The instructions for these sacrifices are giv10 en in chapters 1–7, but in order to offer sacrifices a priesthood needs to be instituted. This takes place in Leviticus 8–9. The ordination of the priests requires sacrifices to be offered, which explains why the ordination comes after the manual of sacrifice. Once the priesthood is installed, however, problems immediately develop. Two of Aaron’s sons, Nadab and Abihu, offer improper sacrifices before the Lord and are struck down by God. Immediately, the question arises: how can a sinful people live with a holy God in their midst? Will not their sins pollute the shrine, making it unfit for God’s presence? These questions are answered by the rest of Leviticus, which provides laws by which the people of God can order their lives in such a way as to maintain holiness. And when the people’s uncleanness does pollute the tabernacle, God provides a means of grace in the annual Day of Atonement, which cleanses the people and the tabernacle from impurity (Leviticus 16). 11 Once the instructions are in place for living as a holy community, the people are ready to leave Mount Sinai and continue towards the promised land in the book of Numbers. The Priestly World The priestly worldview that underlies Leviticus sees the world as a highly structured place. The priests who wrote Leviticus also wrote the familiar creation story in Genesis 1. There, we are presented with a world in which everything has a place and everything is in its place. Each plant and animal is created “according to its type” (vv. 1112, 21, 24-25) and each is assigned to its appropriate sphere of existence: land, sea, or sky. And God saw that it was good (vv. 4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25, 31). Yet for the priestly authors, creation is not completed until the building of the tabernacle in Exodus 35–40. Unlike the Yahwist, who shows God living in the midst of humanity in the garden of 12 Eden, the priestly authors picture God coming to dwell with humanity only with the completion of the tabernacle (Exodus 25:8). In many ways, the iconography of the tabernacle reflects that of the garden of Eden. The cherubim atop the ark in the middle of the tabernacle (Exodus 25:17-22) mirror the cherubim who guard the way back to Eden (Genesis 3:24), while the branched menorah with its blossoms (Exodus 25:31-40) calls to mind the tree of life in the garden of Eden (Genesis 3:22-24). When the people of Israel come to worship God at the tabernacle, they are allowed to reenter Eden temporarily. The laws in the book of Leviticus make it possible for God to dwell in the tabernacle by maintaining its purity. But they also serve to protect the people. One of the central ideas behind Leviticus is that God is holy, and, in order to be the people of God, Israel must be holy as well. This is the reason for the oft repeated phrase in Leviticus: “You 13 shall be holy, for I the LORD your God am holy” (19:2; 20:7), often shortened to “I am the LORD your God” (18:2, 30), or simply “I am the LORD” (18:5; cf. Exodus 6:2). The people must be holy not simply because they should imitate God, but also because when the holy came into contact with the unholy, the latter was in danger of being destroyed. An example of this can be seen in the death of a man named Uzzah, who touched the ark of the covenant when David was transporting it to Jerusalem (2 Samuel 6:68). Uzzah was unholy, so his contact with the ark brought about his death. The ark was enshrined in the tabernacle, so any contact with the tabernacle required the people to be holy, lest they suffer Uzzah’s fate. We must not think, however, that the people of Israel followed the law in order to make themselves holy. Although it is a common misconception that the Israelites had to earn holiness through obedience to the law, this is not 14 the case. Instead, holiness was a gift granted by God to the people when the covenant was made at Mount Sinai. They could never become holy on their own, but through God’s free gift and indwelling presence they were sanctified to be the people of God. But although they could not gain holiness by their own actions, they could lose it, so the laws in Leviticus are intended to allow the people to maintain holiness. By following the law, they could retain the holiness that was a gift from God. This allowed God to live in their midst and made it possible for the people to worship at the tabernacle. And when they did lose their state of holiness, God provided a way for them to regain it, namely, the sacrifices instituted in Leviticus 1–7 and the Day of Atonement in Leviticus 16. Leviticus for Today When we take the time and effort to dive into the book of Leviticus, it has a 15 powerful message for the church today. Far from being concerned with dead laws that weigh us down, Leviticus resounds with the word of God to us in our modern life. Holiness. Holiness is not a concept that is heard much in the modern world, but it is an idea that we should pursue as Christians. Like the ancient Israelites, we have been granted holiness, although we are more likely to call it salvation or righteousness. This holiness has been granted us as a gift through faith in Jesus Christ and we should do everything in our power to make sure that we do nothing to mar that gift. Reading Leviticus, one finds a focus on holiness that calls us—both as individuals and a community of faith— to self-examination. Like the people of Israel, we must make sure that nothing stands between us and our relationship with God. Ritual. Leviticus also reminds us of the importance of ritual. Although it is pos16 sible for ritual to devolve into lifeless repetition, true worship has a profound impact on those who attend. And worship is not a spectator sport. The study of the rituals in Leviticus teaches us that both priests and the laity are active in the worship of God. The rituals in which we participate not only draw us closer to God but also actually transform us. Just as the holiness of the Israelites was restored through the sacrifices, so is our holiness restored each week through our participation in the Eucharist. Wholeness. Finally, Leviticus calls us to consider every aspect of our lives as a part of who we are as Christians. No detail is too small to pass over. From skin irritations (Leviticus 13–14) to bodily discharges (Leviticus 15), and from the second greatest commandment (Leviticus 19:18) to the material our clothes are made of (Leviticus 19:19), all aspects of our lives are important to God. Leviticus shows us a life of faith 17 focused not only on what we do on Sunday but also on the tiniest minutiae of our day-to-day living. It is commonplace to say that the devil is in the details, but for Leviticus, it is God who is found in the details. Drawing Closer to God Despite its status as one of the most neglected books of the Bible, Leviticus can be one of the most rewarding studies for those who take time to mine its depths. It calls us to a life as the holy people of God and provides us with new ways of exploring what it means to be holy. And as we learn to be holy, as the Lord our God is holy, we can draw closer to God, knowing that the Lord is in our midst. 18 Dr. Kevin A. Wilson is an Anglican biblical scholar, who has served as a missionary and professor of biblical studies at Lithuania Christian College in Eastern Europe. Among his several publications is Conversations with Scripture: The Law (Harrisburg: Morehouse, 2006). He maintains a fascinating Bible blog at: http://bluecord.org/biblioblog/. Cover image from Christoph Weigel’s 1695 collection of biblical images, Biblia ectypa, courtesy of the Pitts Theology Library, Candler School of Theology, Emory University. The Bible Briefs series is a joint venture of Virginia Theological Seminary and Forward Movement Publications. www.vts.edu www.forwardmovement.org © 2008 Virginia Theological Seminary 19