Chapter 4: Environmental Enrichment

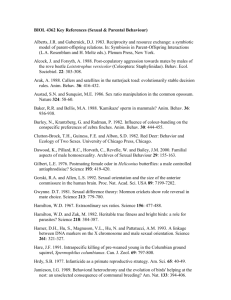

advertisement