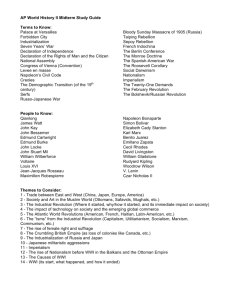

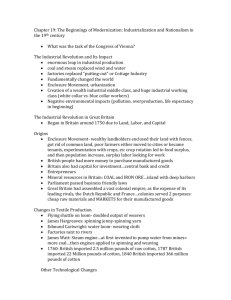

World History Chap 19

advertisement