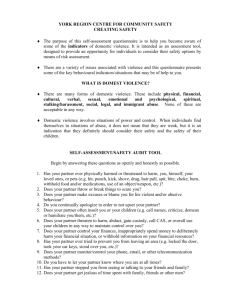

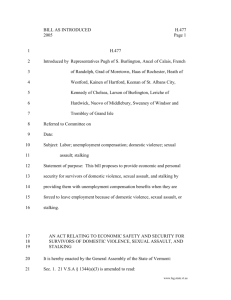

violence against women — domestic violence, sexual

advertisement