ERL@T 1.1 - Trent University

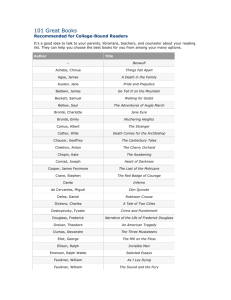

advertisement