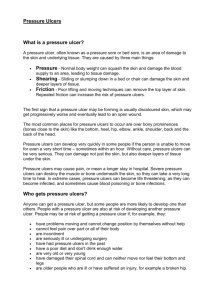

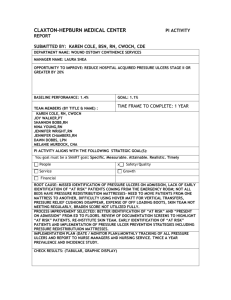

Best Practice Statement: Care of the Older Person's Skin

advertisement