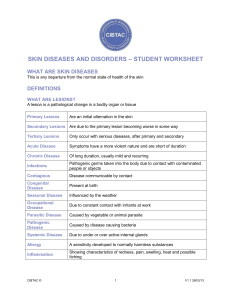

Disorders of the skin

advertisement