China Restores

Sy nagogue Founded in

1 909

Eric Cantor Voted Out Of Congress

Amar'e Stoudemire's Shabbat Short Ribs

Nike's Troubling New Commercial

Search

B OOK S

The Mystery of the Origins of Yiddish Will Never

Be Solved

How an academic field—marked by petty fighting, misguided ideological

debates, and personal proximity to tragedy—doomed itself

By Baty a Ungar-Sargon | June 2 3 , 2 01 4 1 2 :00 AM | Com m ents: 5

Share

21

Tw eet

61

1

0

Em ail

Print

In the U.S., Soccer Has a

Distinctive Voice, and It Belongs to

Andrés Cantor

By Alan Siegel

Remember Us?

Advertise Your

Business Effectively.

Get a FREE Website

Review Today.

Try it Free

1 of 3

Five Things to Know About David Blatt

(Brian Taylor)

The Tablet Longform newsletter highlights the best

longform pieces from Tablet magazine. Sign up here to

receive bulletins every Thursday afternoon about fiction,

features, profiles, and more.

***

This is the second of two articles on the origins of the

Yiddish language.

Where Did Yiddish Come From?

An explosiv e debate erupts from

footnotes suggesting that Ashkenazi

Jews are Europeans

***

Y iddish, it is an understatement to say, is not simply a

language. It’s a culture, an identity, a past both comic

and tragic—one that continues to inspire feelings as

By Cherie Woodworth

diverse as shame and pride, loathing and longing, philoSemitism, anti-Semitism, and accusations of both.

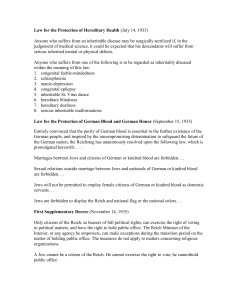

Though Y iddish is not an endangered language, due to

the hundreds of thousands of Hasidic families for whom it is still mother tongue, the

Holocaust decimated the secular Y iddish-speaking community, casting a shadow over the

perceived destiny of the language, a shadow that spreads to discussions of its past. Often

4:08 PM —

Former Maccabi Tel Aviv coach

named head coach of the Cleveland

Cavaliers

China Restores Synagogue Founded in

1909

1:51 PM —

Main Synagogue in the city of Harbin

once held 450 Orthodox congregants

Michael Douglas Continues Son’s Bar

Mitzvah Celebration in Israel

11:54 AM —

No hora-related injuries reported

1 of 3

this time around

Where Did Yiddish Come From?

By Cherie Woodworth — An explosiv e debate

erupts from footnotes suggesting that

Ashkenazi Jews are Europeans

The Mystery of the Origins of Yiddish

Will Never Be Solved

By Baty a Ungar-Sargon — How an academ ic

field—m arked by petty fighting, m isguided

ideological debates, and personal proxim ity

thought of as a fusion of German and Hebrew with some Slavic thrown into the mix, the

language evokes a deep nostalgia for American Jews; in its weaving together of semitic and

gentilic elements, the language seems to encapsulate the tension at the heart of modern

Jewish existence and operates as a stand-in for feelings about Jewish Diaspora. As director of

the Y IVO Institute for Jewish Research Jonathan Brent put it, “The Y iddish language

represents the very conflict at the core of Jewish identity.”

It’s a conflict that also exists—or originated, depending on your perspective—in the academy.

The main debate among Y iddish linguists is about the origin of the language and coalesces

around a single, unexpectedly loaded question: Is Y iddish an essentially Jewish language, one

that contained a Semitic component from the start, whose particular combination of Jewish

and German elements precisely reflects the dance of contact and seclusion performed by

Jews in their European Diaspora? Or is it just another dialect of German?

“It’s a problem that there’s a close relationship between

German and Y iddish,” said Steffen Krogh, a Danish linguist

who studies the Y iddish of Hasidic communities in

Williamsburg and Antwerp. “It’s like a young girl who has

been raped by her father. This girl can’t deny her origins, of

More on Tablet:

course, but she doesn’t want to have anything to do with her

father. This is how many Jews think of Y iddish. But it’s a fact you can’t deny.”

Like Krogh’s overwrought metaphor, the field of Y iddish linguistics is filled with an intensity

that often leaves the tourist astonished. In her article about the mysterious origins of the

Y iddish language, the late Cherie Woodworth described the field’s dramatis personae as “a

very small but committed cadre of scholars”—a wildly tactful understatement. One

metonymic step away from the Holocaust’s devastation, the tiny field of Y iddish linguistics

has ballooned in importance, becoming a place where both the past and the future of the

Jewish people is battled over, one phoneme at a time, through a combination of academic

and extra-academic means. Threats of legal action are par for the course. So are character

assassinations, pseudonymous academic hits, accusations of lunacy, and denials of the

existence of the Jewish people.

It’s gotten worse over time, but it’s almost always been thus. Take one example from nearly

three decades ago, a mess that ensnared a large group of some of the field’s boldest names. At

the center of it was Dovid Katz, a leading Y iddish linguist. Born in Brooklyn, Katz is the son

of Menke Katz, a Y iddish poet who spoke to his son only in Y iddish. Katz then studied Y iddish

at Columbia with Marvin Herzog. According to his Wikipedia page, “For eighteen years

(1978-1996) he taught Y iddish Studies at Oxford, building from scratch, sometimes singlehandedly, the Oxford Programme in Y iddish.” In 1999, he relocated to Vilnius, Lithuania, to

work on his atlas of in-situ Y iddish speakers, an ongoing project. He established the Vilnius

Y iddish Institute at the University of Vilnius, but he has since left; Katz was discontinued

from his post when he became a political dissident for opposing Holocaust obfuscation (about

which he wrote for Tablet). He has since had a role as a judge on the British TV series Best

Jewish Mum. In addition to being deeply respected for his linguistic contributions, Katz is still

remembered by linguists with exalted chairs at American Universities for the parties he threw

in the 1970s and ’80s, where friends would meet his father in Brooklyn and speak Y iddish

until 8:00 in the morning.

Back in 1985, Katz, then a professor of Y iddish at the Oxford Centre for Postgraduate Hebrew

Studies, held the First Annual Oxford Winter Symposium in Y iddish Language and

Literature. The proceedings were published by Pergamon Press in 1987 in a volume titled

Origins of the Yiddish Language. The next year, a review of the book appeared in Language,

the very respected journal of the Linguistic Society of America. The review consisted of a

scathing critique of many of the papers included, indeed, almost all the papers but the one

written by Paul Wexler, a professor of linguistics at Tel Aviv University. The review, penned

by one Pavlo Slobodjans’kyj, concluded that “the infelicitous combination of many

inadequate papers and the editor’s laissez-faire policy—which lets pass a plethora of errors in

formulation, citation, claims, and typography—cannot be alleviated by the participation of

several illustrious Y iddishists.”

to tragedy —doom ed itself

Jewish 12-Year-Old Shocks Reality TV

Judges

By Tov a Ross — Aspiring com edian Josh

Orlian deliv ers dirty jokes on America's Got

Talent

@TA B LE TMA G ON TW I TTE R

Michael Douglas continues son’s bar

mitzvah celebration in Israel (no

hora-related injuries reported this

time): http://t.co/xiviKdwX2x

Follow

24.7K follow ers

3:52 PM

Tablet Magazine

Jewish Voices From the Front

Lines of Donetsk Like 59,126

By Av ital Chizhik — Letters from the

besieged city in Ukraine, from which

Jews are m aking plans to flee civ il

unrest and political turm oil

OU R W E E K LY P ODCA S T |

I TU N E S

Taking on Tamarind, a Staple of

Syrian Jewish Cooking, With

Aleppo’s Culinary Ambassador

Cookbook writer Poopa Dweck shares

the key to her sav ory delights

Get the latest from Tablet Magazine

on culture, religion, and politics

Email address

F R OM OU R P A R TN E R S

“Fun” Guitarist Jack Antonoff Has a Jewish

Punim and a Big, Big Heart

The Geniuses Behind Hello Flo’s Viral “Cam p

Gy no” Video Hav e A New Gem

How the Yiddish Radical Press Helped Inspire a

Fem inist Phone Interv ention

Jews Watching TV: The Bachelorette with Andi

Dorfm an, Episode 6

Dovid Katz, who had edited the book under review, was furious. “We all knew it was Wexler

by the style and the argument,” Katz told me on the phone from Vilnius. He called Sarah

Thomason, the longtime editor of Language and a professor of linguistics at University of

Michigan, demanding a retraction. He insisted that Pavlo Slobodjans’kyj’s review was

published under a pseudonym, a practice not looked upon kindly in academic discourse,

especially when the review lauds one’s own work and pans everyone else’s.

Cookbook author Dana Slatkin?s culinary

fairy tale

Thomason said she was soon inundated by complaints. “I got really tired of getting phone

calls from England from Dovid Katz and his people,” she recalled. But Thomason felt

The Slow Death of the Real Housewiv es of

Orange County

Com edian Jenny Slate in ?Obv ious Child?

Real Housewiv es of New York Dude Ranch

Recap

compelled to pursue the matter due to the seriousness of the allegations and got in touch with

the person who had peer-reviewed Slobodjans’kyj’s review. She told him of Katz’s allegations

against Wexler, “And he said, ‘Oh, yeah, I thought you knew who wrote it.’ I said, ‘Y ou

might have mentioned that!’ He said, ‘Well, suppose you knew who it was, what would you

do?’ And I blew up. ‘What would I do? People publishing reviews of books they contributed

to, published by enemies of theirs—in my journal? No! I would raise the roof!’ ” Thomason

said that it became clear that Pavlo Slobodjans’kyj was “a pseudonym for someone who didn’t

like Dovid Katz. Otherwise why would he write it? Everything pointed to Paul Wexler, but

since he never admitted it to me, I couldn’t put anything in the journal.”

At L.A. cultural center, Middle East translates

to coexistence, not conflict

Adelsons to donate $2 5M to West Bank's Ariel

U.

Activ ists aim ing to steer Israeli gov ernm ent

funding to non-Orthodox

Jewish MIT student killed in fall on India trip

Thomason decided to do some sleuthing. The review had come postmarked Waltham, Mass.,

so she asked her daughter, who was studying at Harvard, to go to the address supplied and

see if Pavlo Slobodjans’kyj existed. When her daughter knocked on the door, it was opened by

Paul Wexler’s mother-in-law.

“She was a quick thinker,” Thomason recalls.

‘By the time I got out of that mess, I

“She said, ‘Y es, he exists,’ ” and went on to

hoped never to hear about Yiddish

assert that Slobodjans’kyj was staying with

Wexler and that Wexler was helping him out. linguistics again’

From Thomason’s perspective, whether he

was a real person or not was almost beside the point. “It didn’t matter if he existed,”

Thomason said. “He didn’t write the review.”

Thomason said she can’t remember at what point Katz started to threaten to sue her, but she

thinks it had to do with a remark she made to the effect that Y iddish linguistics seemed to be

an extremely contentious field. But when Katz threatened to sue, the Linguistic Society of

America got involved, afraid of losing their insurance. “The threat to sue me over a book

review!” She recalled recently, still dumbfounded. “I don’t know if you know how bizarre that

is.”

Eventually, Thomason published a correction, and then an apology: “In Volume 64, Number

4 (1988) of this journal, a review appeared of a book edited by Dovid Katz entitled Origins of

the Yiddish Language. The name of the reviewer was given as Pavlo Slobodjans’kyj. The

Executive Committee of the Linguistic Society of America now has strong reason to believe

that a Y iddish language scholar named Pavlo Slobodjans’kyj does not exist and that the

review was submitted pseudonymously. The Executive Committee apologizes to our readers,

Dr. Katz, and the contributors to this volume. Neither the editorial office of the journal nor

the Officers and Executive Committee of the Linguistic Society of America played a knowing

role in this matter.”

Y ears later, when Thomason found herself introduced to Wexler at a conference, she refused

to shake his hand. “My conclusion was, these people all deserved each other. They were all

pretty unpleasant. By the time I got out of that mess, I hoped never to hear about Y iddish

linguistics again,” she said, adding: “It’s too bad, because it’s a really interesting field.”

***

“Academic Y iddish is a very strange thing,” Dara Horn, a Y iddishist and novelist, told me.

“There’s this self-consciousness to Y iddish. No one believes that it’s a language. The people

who are speaking it don’t believe it’s a language. There was an inferiority complex attached to

Y iddish,” Horn explained, because literacy and religious texts were associated with Hebrew,

the status language in terms of scholarship and literature.

Enter Max Weinreich, the father of 20th-century Y iddish linguistics. Born in what is now

Latvia, Weinreich was raised in a secular, German-speaking household. But he became

enamored with the language spoken by the Jews around him at an early age, and after

earning a doctorate in linguistics, Weinreich established the Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut

—Y iddish Research Institute, known as Y IVO—in 1925, in his apartment in Vilna. Though

Y IVO acquired its own building in 1929, the destiny of academic Y iddish has remained fused

with Weinreich’s own physical and intellectual journey. The outbreak of World War II found

Weinreich en route to a linguistics conference in Denmark, so he made his way to New Y ork,

and so did Y IVO.

Max Weinreich’s theory of the origins of Y iddish is the one most are familiar with: In the

Middle Ages, Jews migrated from France to an area in Western Germany known as the

Rhineland. In France they were speaking a language based on Old French with a HebrewAramaic component called Judeo-French, what Rashi refers to as “Loez.” Upon arriving in

Germany in the 10th century, these Jews created what Weinreich called a “fusion” language

with German. Moreover, explains Paul Glasser in the Y IVO encyclopedia, according to

Weinreich, “Jews never spoke ‘pure German’ but from the beginning of their settlement in

the Rhineland spoke their own language.”

£3.47

BUY NOW

Weinreich was a deeply charismatic individual, whose interests were hardly limited to the

Y iddish language. “I think he was a genius,” said Glasser, who was until recently the dean of

Y IVO and who edited Weinreich’s life’s work, a 700-page History of the Yiddish Language

and a corresponding 700 pages of notes. “Certainly based on the breadth of his interests. If

you look in his bibliography, it’s not just linguistics, it’s psychology, and it’s literature and it’s

history and it’s pedagogy, and youth psychology. He did so much. Would someone else have

done it? Probably not as well. He wasn’t the first, but he was the most important in the 20th

century for sure.” In addition to his interest in Y iddish, Weinreich published in the Forwertz

under the pseudonyms Sore Brener, Y osef Pearl, and A. Berman. His bibliography stands 16

pages long and includes a translation of Freud’s Introduction to Psychoanalysis.

But Weinreich was also

motivated by ideology. Even

some of Weinreich’s followers

concede that his theory reflected

the need to stake a claim for

Y iddish, on the one hand

separating it from German and

on the other hand establishing it

as more than just jargon, or a

debased kind of dialect.

“Underlying that for Y IVO and

for Weinreich was the need to

prove the nationhood of the

Jewish people in the 1920s and

1930s,” explained Jonathan

Brent. Weinreich was also

fighting another war on a

different front: the language wars

of Hebrew vs. Y iddish. Y iddish

was part of a Jewish identity that competed with the Zionist narrative on the one hand and

the religious lifestyle on the other; Y iddish represented a kind of “Diasporic Nationalism,” as

Hillel Halkin, a translator of Y iddish, calls it.

In recent years, Weinreich’s theory has had some push-back. More and more people have

begun to acknowledge that Weinreich did not provide any evidence that modern Eastern

European Y iddish comes from the Rhineland, nor that it was so old. “All this was a

theoretical construction from Max Weinreich, but he provided no corroboration of his ideas,”

said Alexander Beider, who has just written a book about Y iddish origins. “I really admire

him globally speaking, but at the same time, I think that many general concepts of his are

not really linguistic. They are rather ideological.”

“Weinreich had the great fortune that many of the critics of the French theory were dead,”

explained Alexis Manaster Ramer, a retired professor of linguistics, in an email, “and above

all he was in New Y ork in a milieu which was very welcoming to loud European expatriates

like Roman Jakobson, Vladimir Nabokov, Levi Strauss.” Of course, Manaster Ramer

concedes, Weinreich was a major scholar, with a vast erudition that no one could match or

challenge. But “he was going around advocating a simple and radical idea. That it was

basically bunk didn’t bother too many people, since no one had an alternative idea or anyway

no one was loudly proclaiming one.”

Though Weinreich died in 1969, by and large his ideas continued to reign supreme for

decades—having become even a “kind of a linguistic sect,” in Beider’s words.

In the past two decades, the debate has shifted. One the one side of the debate are Weinreich’s

inheritors, who believe that Y iddish originated in Western Germany in the Rhineland and

spread east. On the other side of the debate are those who think that eastern Y iddish, with its

heavy Slavic influence and Bohemian vowel structure, is different enough from western

Y iddish that it must have arisen independently. But because this is Y iddish linguistics, this

debate does not exist so much as rage—intellectually, ideologically, and personally.

***

In the Weinreich camp is one of the most esteemed Y iddishists alive today by most accounts,

Erika Timm, a professor at University of Trier in Germany. Unlike other German scholars,

Timm believes that “Y iddish is one of the ‘Jewish languages,’ in the precise sense given to the

term by Solomon Birnbaum and Max Weinreich,” as she writes in a 2004 article in The Jews

of Europe in the Middle Ages. “Erika Timm proved Max Weinreich’s intuitions,” said Simon

Neuberg, also a professor at Trier. She did this by looking at the earliest written sources of

Y iddish, including Rashi’s biblical and Talmudic commentaries (which, in addition to 3,000

Judeo-French glosses, contain, astoundingly, 24 glosses in Y iddish), and by analyzing

translations of the Bible from Hebrew into Y iddish to show the evolving influence that

Hebrew had on the German parts of Y iddish.

Dovid Katz disagrees with Timm on the question of where Y iddish originated within

Germany. While he accepts that the Jews in the Rhineland spoke a “Germanic based Jewish

language with a Semitic component,” he disputes that this language was Y iddish. Rather,

according to Katz, the Semitic component of Y iddish goes back to a sound system consistent

with manuscripts from the Danube region, which is further east than the Rhineland, where

the true Y iddish originated, while the language spoken in the Rhineland went extinct. In

other words, the linguist’s model (east to west) goes in the opposite direction of the historian’s

model (west to east).

Furthermore, the Semitic components in this eastern-born Y iddish can be traced back to

ancient times. “I was rebelling against the theory that Jews once spoke a purely Germanic

language that then over centuries acquired Hebrew and Aramaic purely through the study of

Hebrew texts,” Katz told me over the phone from Vilnius. “There’s a huge amount of

linguistic evidence for that, that it could not have come from books,” he said, contra Timm.

For example, the Y iddish word for details is protim, but the singular, detail, is prat. “The /a/

in prat reminds us of Sephardic Hebrew. I have traced this system of inherited vowel

alternations to Palestine in the late first millennium A.D.,” Katz said.

In Katz’s theory, the Jews arrived in what Katz calls “the cradle of Y iddish,” the city of

Regensburg, speaking Aramaic. It is this spoken language that provided the source material

for the Semitic component of Y iddish, spreading both further east as well as west, to the

Rhineland, replacing whatever language the western Jews were speaking. Before this

language replacement, the eastern Jews of the Danube region referred to the western Jews of

the Rhineland as “Bnei Hes”—those of “h”—because the western Jews pronounced the “ch”

sound (the sound that opens the word Hannukah) as “h,” whereas the Bohemian Jews

pronounced it as we do—as “ch”—and were called “Bnei Ches.” For Katz, this comes from an

ancient pronunciation, brought by Palestinian Jews in a modified form all the way to

Germany where it proceeded to become the Semitic component of Y iddish. The “ch” of the

Bnei Ches is indicative for Katz of both the ancient origin of Bohemian Y iddish as well as the

easterly location of Y iddish’s origin.

Further proof for Katz’s theory

comes from biblical words that

are replaced later in the Bible by

other biblical words, for example,

the word chag is replaced by

yontif in the Book of Esther;

Y iddish takes yontif, not chag.

“Y iddish always has the latest

historic meaning, which would

not have been the case if they had

come out of the Bible,” Katz said.

Y iddish always preserves the

latest, “coming down the line”

rather than “jumping out of the

text.”

Despite disagreeing with

Weinreich regarding the place of

origin and language of the Jews

immediately prior to Y iddish, Katz views himself as an inheritor of the great Y iddishist.

“Ironically, by positing an inherited Semitic component, my own view is ‘more Weinreich

than Weinreich’ in some sense,” he wrote to me in an email.

On the other side of the spectrum are those, like Alexandre Beider, who has a doctorate in

applied mathematics from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology. Beider believes

that western and eastern Y iddish are simply too different to have a common origin. Rather,

Jews spoke German dialects until the 14th century, when gradually their dialects became

different from those of their co-territorialists. “From the sources documented, we see no trace

of any fusion of Hebrew and German before the 15th century,” Beider told me on the phone

from Paris, where he lives. Beider started out life as a mathematician and theoretical

physicist in the former Soviet Union but found himself drawn to Jewish history. He has

written two books of reference, one about Jewish first names and one about Jewish last

names.

But Beider is not even the most far afield from Weinreich. For when fields are weak and

orthodoxies reign, a fringe tends

to develop; in Y iddish linguistics,

that would be Paul Wexler.

***

Wexler is a professor of Y iddish at

Tel Aviv University who holds the

controversial position that

Y iddish is neither German nor

Jewish but a Slavic language

with German and Hebrew words

slotted into Slavic grammar in a

process called “relexification.”

Wexler began by refuting

Weinreich’s claim that the Jews

came to Germany from France

by disputing the French origin of

the Romance elements in Y iddish. He argued that there is no way that these words could

have been derived from French, based on the existence of components that French doesn’t

allow. Instead, Wexler believes and has argued extensively that Y iddish is a Slavic language

with a new German and Semitic lexicon. “It’s pretty straightforward,” he told me on the

phone from Tel Aviv University. “If you take the Y iddish text and translate it to German and

Polish, you immediately see that the grammar of Y iddish is exactly like Polish. It’s like a

mirror image of Polish.”

“The syntax and phonology of the language are predominantly Slavic,” he argues in a 2012

article in a Slavic philology periodical. “There is very little in the grammar of the language

that is unambiguously German.” For example, where German requires an umlaut when

adjectives go superlative (strongàstronger would be starkàstaarker), Y iddish does not

(starkàstarker). “The lack of umlaut in Y iddish,” Wexler argues, “has its origins in the Slavic

languages.” He also shows that certain words in Y iddish have significantly different

meanings than their German counterparts, for example, where German has bluehen—to

bloom—Y iddish has blien; but when you add the prefix ver in German or far in Y iddish, you

get radically different meanings: verbluehen means to wilt, while farblien means to begin to

blossom. Furthermore, the “so-called ‘Hebrew’ component turns out to be neologisms formed

from existing Old Hebrew roots invented mainly by Y iddish speakers,” Wexler argues. “The

situation with Slavic is exactly the opposite; the number of genuine Slavisms far outweighs

the number of ‘Slavoidisms’ in Y iddish, thus suggesting that Slavic is the oldest component of

Y iddish.”

The word Ashkenaz itself, he argues, only

‘I deny the existence of the Jewish

acquired its present referent—Jews of

people. Ninety-five percent of the

Germany—after the 11th century. It comes

from a biblical word that signified the

Jews are of Iranian origin.’

Scythians, in other words, the Iranians; for

Wexler, this provides a crucial clue as to where the Jews came from and who they were prior

to this date. Indeed, Wexler does not believe that the Jews were forced out of Palestine in the

Roman period, but rather, that the Ashkenazi Jews are descendants of Iranian, Turkic, and

Slavic converts to Judaism.

And here’s where things get thorny. “I deny the existence of the Jewish people,” Wexler told

me on the phone. “Ninety-five percent of the Jews are of Iranian origin.” But Wexler insists

that he did not set out to prove such an extra-linguistic thesis. “This was not my goal. It turns

out to be the logical conclusion of my linguistic theories.”

Other linguists have not taken kindly to the Slavic hypothesis, nor to its author. “I have no

impression that Paul Wexler is searching for the truth,” said Beider. “Sometimes I even

wonder if he himself believes in what he writes. If he is not believing, but making a

provocation, his writings of the last 20 years are oriented just to prove that Jews are not

Jews. In this case, there is nothing to discuss.” Indeed, though he has a following amongst

non-specialists, most linguists disagree with Wexler. “I respect him as a linguist, but I don’t

agree with him,” said Steffen Krogh. Simon Neuberg called the relexification theory “very

adventurous” but said ultimately it “seems more of a marketing trick.”

And, one imagines, that bizarre journal dust-up didn’t endear him to his colleagues in the

field. When I asked Wexler if he was Pavlo Slobodjans’kyj, there was a pause. “No,” he finally

said and offered a litany of facts about the mysterious Pavlo. “I know him vaguely. He was in

America. I met him, I can’t remember at the moment how. He was interested in Slavic

literature and language, his main specialty was Russian. He was Jewish. I know that he went

back to Ukraine in the ’80s for family reasons. I think one of his kids had cancer. After that, I

lost contact.”

For his part, Manaster Ramer has come to believe that Wexler and Weinreich—ostensibly

two opposing poles on a spectrum—are in fact part and parcel of the same culture, one that

puts the cart of ideological conclusion before the scientific horse.

***

Alexis Manaster Ramer was not easy to find. Now in his fifties, Manaster Ramer was born in

Poland to Holocaust survivors and emigrated at a young age to the United States. He

emerged onto the field of linguistics as a young prodigy in the 1980s when he got his

doctorate at the University of Chicago. It is hard to imagine his equal in terms of linguistic

credentials. He was the first person to organize a conference on the mathematics of language.

He has published on Australian, Eskimo, Austronesian languages, Indo-European, UtoAztecan, Nostratic, Altaic, Haida-Nadene, Pakawan/Coahuiltecan, Tonkawa-Nadene, Vedic

and Homeric poetics, and medieval Y iddish. Despite this, he is currently unaffiliated with any

institution. He taught linguistics at University of Michigan and computer science at Wayne

State University before he was forced to retire due to a mysterious illness. He was

subsequently honored by a worshipful festschrift titled The Linguist’s Linguist: A Collection of

Papers in Honour of Alexis Manaster Ramer. He now splits his time between Bulgaria and

Venice Beach, Calif., and if you catch him on a good day, he will indulge questions about

Y iddish linguistics and answer them with lengthy, often furious emails that ultimately make

surprising, even unnerving, sense, methodically devastating the arguments of others.

For instance, Manaster Ramer takes issue with Wexler’s claims that Y iddish is a Slavic

language. Per Wexler, Y iddish’s lack of umlaut proves that it could not be descended from

German. But Manaster Ramer argues that by that logic, neither English nor Dutch would be

considered Germanic languages, and neither would many German dialects, since they too

have lost their umlaut in many of the same places where Y iddish has. Languages consistently

lose their umlauts through contact and evolution. The loss of a feature like an umlaut is a

sign of a language’s distance from its source—the umlaut-bearing German—rather than its

closeness to another source—the non-umlauted Slavic.

Along similar lines, the fact that

Y iddish has some words that

have evolved beyond recognition

as German, while its Slavic words

are still highly recognizable as

Slavic, is another sign that the

Slavic influences are later, not

earlier, as Wexler claims. Wordchange is an example of

something that happens to

languages as they stray from

their sources. The less time a

feature or an influence, like

Slavic, has been in a language,

the less time it will have to evolve

and the more similar the words

will be to the source. The more

time a feature has been part of a

language, the less like its origin

that feature will be. “The Romance elements of Y iddish are often quite evolved beyond their

Romance sources,” Manaster Ramer writes in an email, “and similarly the German ones. The

Slavic ones much less so. This is the opposite of what Wexler’s theory predicts.”

Manaster Ramer also disputes Beider’s claim that Y iddish could have originated in two

places. “There is no way Jews in Eastern Europe could have independently invented the very

specific Romance and Hebrew features and western German Jewish names,” he wrote in an

email, “but they could easily have changed their German to agree with that of their eastern

German neighbors over hundreds of years of interaction in both eastern Germany and

Bohemia.” Features of a language can change in one generation; that doesn’t make the new

version a different language than the old. An analogy: John F. Kennedy, Jr. didn’t pronounce

the final “r,” which his children then reintroduced into their speech. By Beider’s logic, they

would be speaking different languages.

As for Katz, Manaster Ramer believes his argument is actually brilliant. “This is exactly what

linguists are supposed to do,” he said: come up with a theory based on facts. It’s one of the

cleverest arguments in the field, he said—one that has been underestimated because “there is

no Aramaic lobby.”

But Manaster Ramer also thinks Katz is wrong. He points out that the Maharil, a 14thcentury Talmudist from Mainz in the Rhineland, used the word yontif, too, in which case,

this can’t be proof of the Danube thesis. Furthermore, the Kaufmann Haggadah, a Sephardic

Haggadah from the 14th century, also has the vowel change we see in prat/protim; if this is

the case, this can’t be unique to the Danube region and thus cannot rule out a Rhineland

origin for Y iddish.

And what of the Bnei Ches and the Bnei Hes, which provided evidence for Katz’s claim that

Y iddish originated in Regensburg and replaced the Rhineland dialect? These don’t necessarily

lead to Katz’s conclusion, Manaster Ramer said. Katz assumes that because western Jews

ultimately stopped being Bnei Hes and selected the pronunciation of Bnei Ches means either

that the population of Bnei Hes was replaced, or that the remaining Rhineland Jews replaced

their entire language. But there is another option—they could have simply changed this one

feature of their language, just like JFK’s kids. Even if Y iddish had originated in the Rhineland

and moved east, as Weinreich argued, there is no reason that the Rhineland population

couldn’t have corrected their language from Hes to Ches to fit their texts at some point, or

been influenced by an influx of Ches-pronouncing Jews from another country, both of which

are consistent with Jewish behavior throughout the ages. Indeed, transcriptions of people’s

names from the Danube region show Hes pronunciation as late as the 14th century,

suggesting that even in the east, the Ches pronunciation is not a modification of an ancient

pronunciation, but rather itself a 14th-century linguistic change. Indeed, this was Max

Weinreich’s theory on the subject.

Rather, Manaster Ramer believes that Roman Jews speaking a Romance dialect, not French

but related to it, lived in both western and southern areas of what would become Germany.

When the German tribes invaded the Roman territories, these Jews learned perfect German.

His evidence for this comes from the Romance words in Y iddish, as well as certain names

that bear features that couldn’t possibly have come from French. For example, Beyle was a

women’s name frequently found among the victims of the first crusade. The name is almost

certainly not French, because if it were, the vowel would be short to accommodate the double

consonant, like in the French version—Belle. Beyle implies a Romance dialect that has a long

vowel, rather than a long consonant. Another example would be the word sterdish—defiant—

which looks German because of the suffix but can’t be of German origin, or it would begin

with sht. But it also can’t be French because the Old French word begins with a vowel—

estordie—meaning a crazy action.

And those Old French words and names usually cited as evidence that the earliest German

Jews spoke French probably entered the language centuries later than is claimed. Take for

example the word most often cited to prove the French origin of the Ashkenazi Jews: cholent,

the slow-cooked, slow-digested Sabbath food. Received wisdom tells us that this word is

mentioned in some of our earliest sources of Y iddish, such as the writings of Isaac ben Moses

of Vienna, otherwise known as the Or Zarua, who lived from 1200-1270. But if one looks at

the text of the Or Zarua, one sees immediately that the word cholent is glossed. The Or

Zarua, visiting his Rabbi (one of the Rabbeinu Tam) in France, describes the practices

deployed by French Jews for heating “their cholent, in other words, tamun.” Rather than

proof that Ashkenazi Jews called the beans and meat mixture cholent, the Or Zarua provides

quite the opposite, proof that his readers called it something else. In other words, while the

French word did eventually become a Y iddish word, it is not evidence for anything

approximating an Old French origin for the Ashkenazi Jews.

So, if the Jews who started speaking Y iddish originally spoke German, how and when did the

Semitic component enter the language? The question itself is unscientific, said Manaster

Ramer, ignoring as it does the historical context in which Y iddish came to be, which

incidentally was a time in which German too underwent a similar process, incorporating

loan words from Latin. Indeed, said Manaster Ramer, the influence of Latin on German was

far greater than the Hebrew and Aramaic influence on Y iddish, “and yet no Y iddishist seems

to asks, why does the massive Latin influence on German not mean that German is not

German, if the much smaller Hebrew influence on Y iddish is supposed to mean that Y iddish

is not German,” he wrote in an email. Any language spoken by polyglot people can

incorporate words from their second or third language at any time. Furthermore, he said,

almost all of the Hebrew and Aramaic words in Y iddish are accretions added to the language

after the 13th century.

***

In the end, what’s clear is that the field of Y iddish linguistics is certainly weakening. “There

are no graduate studies in Y iddish in the United States anymore. And it’s almost gone in

Israel. There’s a little in Germany and a little in Warsaw, which is very problematic if you

think about the Jewish people,” said Rakhmiel Peltz, director of the Judaic Studies Program

and professor of sociolinguistics at Drexel University. “I’m in a university that has graduate

programs in inhalation therapy! There’s no Y iddish, but there’s inhalation therapy.” Peltz said

that this is in part due to the fact that there is no distinction between the training experts

receive and that of students.

But it may also have to do with the desire some had to distance themselves from the

mamaloshen. Professor Y osef Haim Y erushalmi, the Salo Wittmayer Baron Professor of

Jewish History, Culture and Society at Columbia University from 1980 to 2008, used to tell a

story about giving an academic lecture that his mother attended. At some point during the

lecture, she turned to someone and said, “Kuk nor vi er shvitst”—Look how he’s sweating. “If

your mother is saying that over your shoulder, it’s not easy to jump into the Y iddish pool,”

Peltz concluded.

“The standards are a lot lower,” both today and in comparison to other fields, admitted Katz.

“The professors writing are professors of Slavic, or a mathematician. It’s a lively field, but I

don’t believe the debates are at the level that they were a generation ago, when there were

major incumbent professors of Y iddish who have now died.”

As a result, Manaster Ramer believes the field of Y iddish linguistics tolerates and even

encourages charlatans, whose work is treated with seriousness. As he explained in an email,

“When you read Mein Kampf, you do not respond by saying Prof. Hitler has made a cogent

and important case for Jews being vermin who should be exterminated, however on p. 250

we note that his discussion of whatever the fuck it is is perhaps not documented sufficiently,

and we might consider the alternative theory that they are merely scum who deserve to be

put to slave labor or slowly starved to death, although of course in light of his powerful

arguments passim, very likely the former hypothesis is correct after all. This is the kind of

mealy-mouthed and indeed respectful reaction that even the most irresponsible and

incompetent work in this field gets. And this makes the situation much worse than if blatant

error and deliberate misrepresentation were simply ignored the way scientists often simply

disregard pseudo-science.”

Manaster Ramer—like many of the other prominent Y iddish linguists—certainly has reason

to be emotional about Y iddish. His mother survived the war partially due to the fact that she

was a native speaker of Polish and didn’t have the distinctive Y iddish accent, which is

precisely what sent many Jews to their graves as the surest means of identifying them as

Jews. (Her horrific experiences during the Holocaust are chronicled in a 1983 video from the

Holocaust Memorial Center oral history project.) The lack of accent, coupled with the fact

that neither of his parents looked stereotypically Jewish, enabled them to pass as Catholic

Poles.

But, as people like Manaster Ramer might argue, allowing personal connections to morph

into ideological motivations is the opposite of science—and the tendency to do so on the part

of so many in Y iddish linguistics is what’s dooming the field. Steffen Krogh—who defined

Manaster Ramer’s approach to Y iddish as “completely unsentimental”—remembers once

confessing to his friend that he was worried about the future of Y iddish.

“He said to me,” recalled Krogh, “ ‘Steffen, I am only worried about its past.’ ”

***

Sign Up for special curated mailings of the best longform content from Tablet Magazine.

1

2

3

4

5

View as single page

Batya Ungar-Sargon is a staff w riter at Tablet Magazine. Her Tw itter feed is @bungarsargon.

MORE IN: ACADEMIA

MAX WEINREICH

Share

21

AUSTRIA

PAUL WEXLER

Tw eet

CHERIE WOODWORTH

POLAND

61

DANUBE

RHINELAND

1

Y IDDISH

GERMANY

LINGUISTICS

LONGFORM

Y IVO

0

Em ail

Print

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

Rick Perry: 'I'm More

Ancient Moroccan

Jewish Than You Think Jewish Texts, Now

I Am'

Available Online

Anti-Semitic Hungarian Michael Douglas

Politician Finds Out

Celebrates Son's Bar

He's Jewish, Gets

Mitzvah in Israel

Circumcised

Dov Charney Booted From

Am erican Apparel

Readers Are Tired of Ov erpay ing

for Ebooks. Here's their Secret to

89 -Year-Old Suspected

Auschwitz Guard Arrested

Getting Bestsellers for Free (The

BookBub Bulletin)

Where To Eat in Tel Av iv This

Sum m er

Australia’s Ultim ate Dining

Story of Moroccan Jewry Now

Av ailable Online

EU Official Goes Off On ‘Zionist

Bullshit’ Em ails

Locations (Restaurant

Australia)

The Dum best Test Answers Of

All Tim e (Bossip)

Com ics Unm asked: Pushing The

Boundaries (The British

Library )

From a Germ an King to British

Born - See the Ev olution of the

Roy al Fam ily

Palaces)

Composer David Lang Thinks

the Pulitzer Prize Is Creepy,

Would Rather Bang on a Can

With his influential alternativ e

m usic m arathon this weekend,

the anti-institutional artist

grapples with accolades

By Nathan Schiller

(Historic Roy al

[What's this]

We Recommend

Why You Should

Colour Your Grey at

Home

Sponsored Content by Taboola

6 Tips To Keep Your

Dog Healthy

GoW eLov eIt

Embracing the

inevitable:

Consumerisation (an…

ISA Investing – Your 1

Minute Guide

Ha r g r ea v es La n sdow n

Ha ir Color for W om en

CFO

World’s Top 10

Top 5 reasons to pay

Snorkeling Destinations off your credit card

Revealed: How to grow Did your Ancestor

your business via

Storm Normandy? How

exoprts

to Figure It Out?

Esca peHer e

Zopa .com

T h e W eek

A n cest r y .co.u k

Add a comment...

Also post on Facebook

Posting as Dovid Katz (Not you?)

Comment

Mumme Loohshen - An Anatomy of Yiddish, by Joseph Witriol

As with the earlier article by Cherie Woodworth, may I add a link to my late father's Mumme

Loohshen - An Anatomy of Yiddish. He wrote it in 1974/1975 and declares that the "Yiddish

recorded in this book is that spoken by my mother, mumme loohshen. In the few instances

where this deviates, or seems to deviate, from “printed” Yiddish I still record what I heard my

mother speak."

http://mummeloohshen.wordpress.com/

Reply · Like ·

1 · Follow Post · about an hour ago

Leah Chanin ·

School

Top Commenter · Stephens College, Southern Methodist Univ. , Mercer Law

What a horrible analogy, Mr. Krogh! Comparing a girl raped by her father to almost anything else

is truly disgusting.

Reply · Like · Follow Post · 3 hours ago

Henry Gottlieb ·

Top Commenter

This is almost as important as, lighting the chanukah candles left to right or right to left

Reply · Like · Follow Post · 44 minutes ago

Jacques Borek ·

Top Commenter

I am amazed by the style and futility of this Article: pages of vain "stories and empty debate to tell

Nothing. I join here some observations I quickly noticed on a page I just copy paste right now

with no much correction. I hope that people will go to Library and have a look on Genral History

and Geography of Europe and focuse on realities and not wishful-nthinking.

That rape is not a vain analogy: the refusing of Jewish Heterogeneity and multiple proselytrism

is one of the most stupid attitude of the Jews toxward their true origin. They should be all in

fatherline Haplogroup T from Mesopotamia and they are 4% maximum. So Abraham had no

biological posterity..... but a great Moral one...

My excerpts and Notes of Reading: (ndl in french)

In the Middle Ages, Jews migrated from France to an area in Western Germany known as the ...

See More

Reply · Like · Follow Post · 33 minutes ago

ARTS & CULTURE

LIFE & RELIGION

NEWS & POLITICS

THE SCROLL

Books

Observ ance

United States

VOX TABLET

Film

Food

Middle East

Music

Fam ily

World

ABOUT US

Telev ision

Personal History

Sports

CONTACT

Theater & Dance

Notebook

Visual Art & Design

Search

TABLET RSS FEEDS

NEXTBOOK PRESS

Tablet Magazine is a project of Nextbook Inc. Copyright © 2014 Nextbook Inc. All rights reserved. | Terms of Service & Privacy Policy

Follow us