Art in Motion / Guayasamínʼs Ecuador Unframed

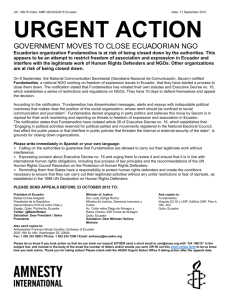

advertisement