Assessing Organized Crime: The Case of Germany

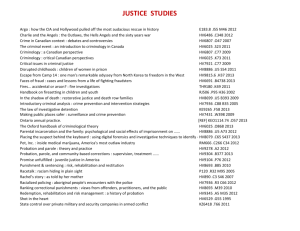

advertisement