THE THREATS POSED BY TRANSNATIONAL CRIMES AND

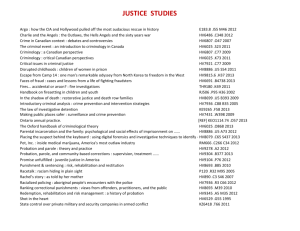

advertisement