Thesis

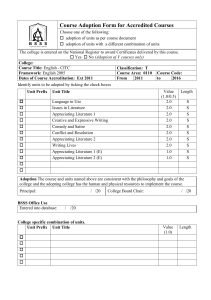

advertisement