Parenteral-nutrition-manual-September-2011 Manual

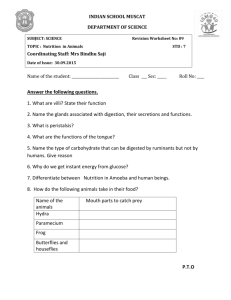

advertisement