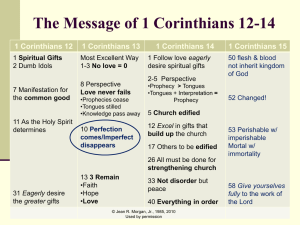

Rhetorical Analysis of Paul's Argument in 1corinthians 13

advertisement