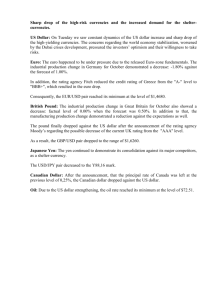

The International Role of the Dollar and Trade

advertisement