Keeping Your Parish Financially Healthy

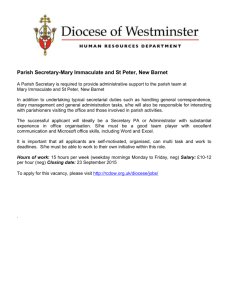

advertisement