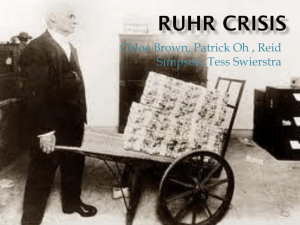

Public borrowing in harsh times: The League of Nations loans revisited

advertisement