1 POLICY REFORM AND NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

advertisement

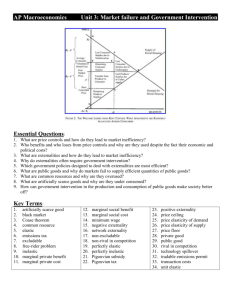

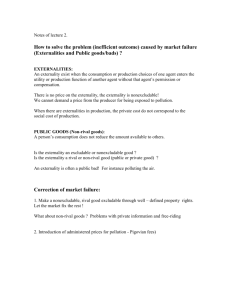

POLICY REFORM AND NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT WEEK 1: DAY 3 MARKET FAILURE by Janet EGDELL, University of Aberdeen CONTENTS 1. 2. 2.1. 2.2. 3. 3.1. 3.2. 3.3. 3.3.1. 3.3.2. 4. 4.1. 4.2. 4.3. 4.4. 4.5. 5. 6. 7. INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES HOW THE MARKET WORKS Demand, supply, and the price mechanism Efficiency of resource allocation WHY THE MARKET FAILS Failure associated with market structure Failure associated with the market mechanism Failure associated with non-marketed goods Externalities Public goods EXAMPLES OF MARKET FAILURE IN THE MANAGEMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Negative externalities, e.g., water pollution Positive externalities, e.g., soil stabilisation Public goods, e.g., agricultural research Poorly-defined property rights, e.g., access to land Short-term thinking, e.g., tree planting SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS REVIEW QUESTIONS ANSWERS REFERENCES LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Spectrum of public/private goods LIST OF FIGURES Figure A. Figure B. Figure C. Figure D. Figure E. Figure F. Figure G. Economics of pollution Economics of pollution Economics of pollution Economics of pollution Economics of pollution Edgeworth Box illustrating negotiation over a negative externality Optimal provision of a public good 1 1. INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES This section of the course deals with market failures and how they can affect the management of natural resources. Some natural resources are bought and sold in markets, but many are not. Here, we explore the reasons for this disparity. This section lays the foundation for much of the remainder of this module, which will consider how to make markets work more effectively, or what alternative mechanisms can be used instead to allocate resources. It is important that you understand the reasons why markets work in some situations but not in others. In this section of the course you will • be reminded how a market can be an effective means for allocating resources; • consider the role of prices in the allocation of resources; • distinguish between private and social costs and benefits; • consider the situations in which markets fail to allocate resources to the activities that society as a whole would benefit from; • be able to explain and give examples of different types of externality; • understand which goods and services are public goods; and • be able to apply these concepts to your own experience of natural resource management. Exercise 1: With your neighbour, spend a few minutes making a list of different natural resources. Which ones are sold in markets, and which ones are not? Can you think of some reasons for this difference? 2. HOW THE MARKET WORKS 2.1. Demand, supply and the price mechanism Markets are one way to allocate scarce resources. Within a market, many buyers and sellers can interact to exchange goods and services. The interaction is voluntary and the exchange process is decentralised. Exercise 2: Can you think of some other ways to allocate scarce resources, other than using a market? This exchange relies on the price mechanism. In a market, changes in demand cause changes in price, which act as a signal and an incentive to change supply. Similarly, changes in supply cause change in prices, acting as a signal and an incentive to change demand. In this way, the market moves towards an equilibrium where the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. At this point, there is neither a shortage nor a surplus. 2 If the market is working, the demand price represents consumer preferences and the supply price represents resource use. That is, the full costs and benefits of production and consumption are reflected in market prices. Exercise 3: How would you show, using a standard market diagram, the following: • the effect of an increase in consumers willingness to pay for bread, due to a change in tastes? and • the effect of an increase in the wage rate of farm workers on the willingness of farmers to supply rice? What is the role of prices in each case? 2.2. Efficiency of resource allocation A competitive market can result in a Pareto-efficient allocation of resources, that is, an allocation whereby it is not possible to make any person better off without making somebody else worse off. A competitive market determines how much is produced and who gets it, based on how much people are willing to pay to purchase the good compared to how much people must be paid to supply the good. In a competitive market, reallocation of resources will occur until all of the gains from trade have been exhausted. Consumers try to maximise their consumer surplus, whilst producers try to maximise their producer surplus. They are not seeking to maximise efficiency. However, the price system induces self-interested consumers and producers to make choices that are efficient from society’s point of view. It should be noted that a competitive market may not lead to an equitable allocation, that is, one that is distributionally fair or just. However, it will lead to an efficient allocation. However, markets are not always competitive. Also, the market demand price does not always reflect consumer preferences and the market supply price does not always reflect the full resource costs. In these cases, the market fails to allocate resources efficiently. It is these situations that are going to be considered in this chapter. The upcoming chapters will consider how it may be possible for the government to intervene to correct for such market failures, either through the legal system by redefining property rights, or through adjusting the market system with, for example, taxes and subsidies. 3. WHY THE MARKET FAILS There are three main ways in which the market can fail to allocate resources in the way that would be desirable for society as a whole. These are • failure associated with market structure; • failure associated with the market mechanism; and • failure associated with non-marketed goods. 3 3.1. Failure associated with market structure Inefficiency may result from the lack of competition in some markets, where the market structure is a monopoly or imperfectly competitive. Under imperfect competition, suppliers do not necessarily respond to consumer preferences. Lesser resources may be allocated to the production of certain goods and services so that the firm producing them can obtain higher profits (supernormal profits). Society as a whole may therefore be worse off. 3.2. Failure associated with the market mechanism The efficient allocation of resources only occurs if the information about consumer preference is transmitted to suppliers and the information about resource costs is transmitted to consumers. If there are high transaction costs involved in buyers interacting with suppliers, then the market may not be able to adjust to changes, or not rapidly. In this case, resources may not be allocated in a socially optimal way. 3.3. Failure associated with non-marketed goods Many environmental goods and services are not marketed at all. This means for such goods we have no prices at all, or we have prices that do not reflect the full costs or benefits of the goods and services to society as a whole. The market reflects private costs and benefits, rather than social costs and benefits. Wherever the private and the social costs and benefits diverge, the market will allocate resources in the optimal way for private individuals, but not in a socially optimal way. The following considers, in more detail, this third area of market failure associated with goods and services for which we do not have the correct price that reflects the social costs and benefits. 3.3.1. Externalities Often, the person making a decision does not bear all the consequences of his or her action. For example, if somebody decides to smoke a cigarette, the person sitting next to him or her inhales the cigarette smoke too. Similarly, if a firm located upstream puts waste into the river, another firm located downstream finds they obtain lower quality water. In each of these examples, there is an externality, in the sense that an (external) person bears some of the consequences of the actions of another person. An externality occurs whenever the welfare of some agent, either a firm or household, directly depends not only on his or her activities, but also on activities under the control of some other agent. The interdependence between the two agents is not priced and, therefore, is not taken into account when the latter agent is deciding on how to act. The externality arises from incomplete or non-existent property rights. The consequences of an action on the other person may be good or bad, that is, it may improve their welfare or reduce it. If welfare is improved, then we have a positive externality; if it is reduced, then we have a negative externality. We can also call these external benefits and external costs, respectively. 4 In the case of a positive externality, the actions of one firm or household either reduces the costs of production or increases the utility of people other than the producer or consumer. For example, a beekeeper provides an external benefit to the nearby person who has an apple orchard, which the bees pollinate. By keeping bees, the beekeeper reduces the cost of producing apples to the orchard owner. In the case of a negative externality, the actions of one firm or household either increases the costs of production or decreases the utility of people other than the producer or consumer. For example, a farmer pollutes a river with pesticides and imposes an external cost on the fisherman down the river. By polluting the river, the costs of catching fish are increased for the fisherman. Externalities occur when the social costs and benefits are different from the private costs and benefits. The beekeeper will decide whether to keep bees, by comparing the marginal private cost (i.e. marginal cost to her) of keeping bees with the marginal private benefit (i.e. marginal benefit to her). This ignores the reduction in costs to the orchard-owner. In this example, the marginal social cost (i.e. the marginal cost to the beekeeper less the saving in costs to the orchard owner) is less than the marginal private cost. Similarly, the farmer will decide how much pesticide to apply, by comparing the marginal private cost with the marginal private benefit. This ignores the additional cost imposed on the fisherman, for whom it is now more difficult to catch fish. The marginal social cost is greater than the marginal private cost. For a negative externality: MSC > MC or MSB < MB For a positive externality: MSC < MC or MSB > MB Whenever social and private costs and benefits diverge, the result is an inefficient allocation of resources. The result tends to be too much of the negative externalities and insufficient of the positive externalities. Exercise 4: Complete the following table with two examples of each of the following types of externality: Negative Positive Consumption Production The following diagrams demonstrate the difference between the private and social optimal allocation of resources. Imagine the case of a paper-mill, which in the process of producing 5 paper emits chlorine into a nearby river. The private decision by the paper-mil is shown in Figure A. Assuming the firm aims to maximise its profit, it will continue expanding its paper production until Qp, the point where the marginal cost (to the firm) of producing the paper equals the marginal revenue (to the firm). For simplicity, the marginal cost curve is shown here as a straight, upward-sloping line, though in reality marginal costs might fall at first as fixed costs are spread, before rising as shown here, due to the law of diminishing marginal returns. Marginal revenue is assumed here, again for simplicity, to be horizontal, implying that the papermaking industry is highly competitive. Qp is the optimal amount of paper to produce from the paper-mill’s private perspective. [Figures A to E] Exercise 5: a) Explain to your neighbour why a firm will profit maximise where the private marginal cost equals the private marginal benefit. b) How does a firm decide how much to use of an unpriced resource, i.e. with a cost to the firm of zero? Figure B is simply a transformation of Figure A, indicating the Marginal Net Private Benefit (MNPB), or level of profit, made by the paper-mill. This is calculated as the revenue obtained for selling an extra box of paper less the cost of producing that extra box. The profit-maximising level of paper to produce is again shown as Qp, beyond which point no more is added to the profit level (or MNPB). Figure C now turns to the impact of the chlorine that is emitted during the production process. The nearby river can assimilate a certain level of chlorine. If the paper-mill produces Qa boxes of paper or less, the level of chlorine dumped in the river would be assimilated and thus no pollution problem would arise. Beyond this level, however, pollution is caused which imposes a cost on other users of the river (an external cost). Figure D illustrates this external cost, but now in terms of a monetary value, rather than a quantity of pollution, as shown in Figure C. There is an underlying assumption here that we can put a monetary value on the pollution damage. How this valuation might be done will be discussed later in this module. The marginal external cost (MEC) is zero up to the assimilative capacity of the river, as up to this point there is no negative impact on other users of the river. Beyond a level of paper production of Qa, the marginal external cost rises. This implies that there is a cumulative damage effect: as more chlorine is put into the river, it has an increasingly damaging impact. Figure E combines the Marginal Net Private Benefit curve from Figure B with the Marginal External Cost curve from Figure D. We are interested in the socially optimal level of paper production, that is, taking into account all externalities. This level of production is indicated by point Qs where the two curves cross. At this point the benefits in terms of profit to the firm are balanced by the costs to other river users in terms of pollution. If less paper than Qs is produced, the firm would forego more profit than the cost of the pollution warrants, leaving society overall worse off. Similarly, if more paper than Qs is produced, the additional profit 6 would be less than the cost of the pollution associated with that production, again leaving society worse off. Exercise 6: What would be the impact on the private and social optimum levels of paper production of each of the following: a) an increase in the market demand for paper due to higher incomes? b) new information that indicates chlorine is more damaging than had previously been thought? Three caveats are suggested to the above model, bearing in mind the Precautionary Principle. If the pollutant is toxic or persistent the environment may have no assimilation capacity. Secondly, the above example considered a single pollutant; it is often the case that cocktails of pollutants may be more damaging, and less understood. Thirdly, in this model, pollution damage only occurs when individuals recognise a loss of welfare. This may not be very useful for pollutants that emit low doses over long periods. Exercise 7: Assume that a firm produces organic waste that has the effect of increasing the fertility of neighbouring farmland and thus reducing farmers’ costs. It is impractical, however, to sell the waste to the farmers. The table below shows the firm’s private marginal costs and these external benefits to farmers from the firm’s production. Output (units) Price (£) Marginal (private) cost (£) Marginal external benefit (£) 1 20 16 6 2 20 15 5 3 20 15 4 4 20 16 3 5 20 17 2 6 20 18 2 7 20 20 2 8 20 22 2 9 20 24 2 10 20 27 1 • • • How much will the firm produce to maximise profits? What is the marginal social cost of producing 3 units per day? What is the socially optimum level of output? 7 • • • What subsidy per unit would the government have to pay the firm to encourage it to produce this level of output? How much would it cost the government? If a new farming technology doubled the benefit of the waste to the farmer, what will now be the socially optimum level of the firm’s output? Another way of illustrating a negative externality, is using an Edgeworth Box, indicating the preferences of two individuals for two goods, for example, money and smoke, as shown in Figure F. This emphasises the point that the socially optimal solution will depend on the property rights each person has: do people have a right to pollute, or a right not to put up with other people’s pollution? Take the example of two people that share an office. One of them smokes but the other does not. Smoke is a good for person A, but a bad for person B. This means that unlike the usual Edgeworth Box, smoke is measured vertically from bottom to top for both people. Money is measured from left to right for person A and from right to left for person B, as is usual. [Figure F] Which one of the several equilibria we end up at depends on which endowment we start with. That is, how the money was initially distributed and whether there is a right to smoke, or a right to have clean air. This diagram assumes the money is split evenly between the two people. Possible endowment E’ assumes that person A has a right to smoke as much as he wants and B just has to put up with it. In effect, B will pay A not to smoke, moving to equilibrium X’. At this point the marginal rate of substitution of smoke for money is equal for both of the workers. Endowment E would be the case if B has a right to clean air. In this case, A will bribe B to allow him to smoke, moving to equilibrium X. Alternatively the legal right to smoke and clean air could be somewhere between these two extremes, as with situations where workers are allowed to smoke in some parts of the workplace, but not all. 3.3.2. Public goods Public goods are an example of a particular sort of consumption externality where everyone must consume the same amount of the good. For example, we must all consume the same level of air quality, regardless of whether some of us value high air quality more than others do. Once improved air quality has been provided, all will benefit. Public goods have two particular consumptive characteristics: • non-rival: the consumption of a good or service by one person will not prevent others from enjoying it; and • non-excludable: it is not possible to provide a good or service to one person without it thereby being available for others to enjoy. As it is impossible to exclude others from consuming the good once it is provided, we have what is termed the ‘free-rider’ problem. People can expect to benefit from the provision of the public good, even if they do not contribute towards the cost of providing it. 8 As public goods have large external benefits relative to the private internal benefits, they would tend not to be provided by the free market. As we saw earlier, an individual or firm will decide whether or not to provide a good by weighing the private benefits against the private costs. With these public goods, the benefits will tend to be shared with other individuals or firms (i.e., MSB>MPB), but the costs will not. This makes them unattractive for entrepreneurs to provide. The socially optimal provision of a public good will again be where the marginal benefit to society equals the marginal cost to society. However, the calculation of marginal benefit in this case is somewhat different from that associated with private goods, due to the non-rival characteristic of a public good. If you benefit from clean air, that does not take away from my benefiting from the same clean air. Therefore, to obtain the total marginal benefit from a public good, we have to sum the private benefits (or individual demand curves) of all the individuals vertically rather than horizontally. This is illustrated in Figure G. [Figure G] Consider that this public good is the maintenance of a forest, and two people are being asked to contribute to its maintenance. Both people benefit from the forest, which prevents soil erosion and flooding. Person 1 is asked what area of the forest she would like to see maintained, and would weigh up the marginal benefit to her of maintaining a bit more forest against the marginal cost of providing this. If left to a private contribution, this person would be willing to pay for the provision of an area Q1. Similarly Person 2 would consider the benefit he would receive from maintaining more forest compared to the cost. This person would be willing to contribute to maintain a maximum area of Q2. Left to the market, this amount Q2 is the maximum that would be provided. However, the total benefits to society of maintaining the forest are much greater than the private benefits to Person 2. We should therefore add to this the benefits that accrue to Person 1, giving us a total marginal benefit curve equal to MB1 + MB2. The socially optimal amount of forest to be conserved is Qs, where the sum of the two marginal benefit curves crosses the marginal cost curve. The problem is that we cannot persuade Person 1 to contribute to the maintenance of the forest, as she knows that the amount she would like to see provided (Q1) will already be provided by Person 2’s contribution. As this is a public good, Person 2 cannot prevent Person 1 from benefiting from the area already conserved by Person 2’s contribution. Person 1 can free ride: gain the benefit, whilst not paying the cost. For this reason, the free market will conserve too little forest from society’s point of view. In reality, goods may be neither completely public nor completely private but share characteristics of each. Instead, we have a spectrum of goods, as illustrated in Table 1, some being closer to public goods and some closer to private goods. For example, fish shoals are quasi-private goods. The fish resource is non-exclusive if it is in the open sea. Anybody has the right to take the fish. However, there is rivalry. Once the fish are taken, they are no longer available to other people who are fishing. A public beach may be a quasi-public good. Again it is non-exclusive, as everybody has the right to use the beach. There may be plenty of room on the beach, in which case it is also non-rival. However, there will be a point beyond 9 which the beach becomes crowded, and some degree of rivalry between different users of the beach may be found. Generally, public goods will be provided by the government, as otherwise too little of them or none at all would be provided. Non-pure public goods, that is, those where it is possible to exclude free riders, could be provided by a market, but are often provided collectively by the State. For example, roads may be provided by the government and funded from general taxation, but it is possible to charge a toll for those who actually use the road. Table 1. Spectrum of Public/Private Goods Pure private Quasi-private Quasi-public goods goods goods Non-exclusive Non-exclusive Characteristics Exclusive Rival Rival Only partially rival Rivalry in Annual or Congestible goods Management consumption regular e.g. exceeding the Exclusion easy payments made carrying capacity to provide of a public beach quasi-collective good Bread Migratory fish Closed access Examples shoals nature reserves Groundwater reserves Source: Adapted from Turner, Pearce, and Bateman (1994). Pure public goods Non-exclusive Non-rival Non-rivalry in consumption Exclusion not possible or practicable Scenic views Clean air Clean water Exercise 8: Can you think of some examples of public goods that are provided by the private sector? Should more of these goods be provided than is being provided at the moment? Exercise 9: Which of the following features distinguish public goods from other types of goods (There may be more than one feature)? • Large external benefits relative to private benefits • Large external costs relative to private costs • A price elasticity of demand only slightly greater than zero • The impossibility of excluding free riders • Ignorance by consumers of the benefits of the good • Goods where the government feels it knows better than consumers about the amount people ought to consume 4. EXAMPLES OF MARKET FAILURE IN THE MANAGEMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 10 4.1. Negative externalities, e.g., water pollution Externalities are often related to resources that are used by many different people. For example, a river, throughout its course, is used by a range of people for a variety of purposes. Negative externalities occur whenever one user of the river does not take into account the cost imposed by his or her activities on another user. A factory located upstream may use the river for waste disposal, and in the process pollute the water for other users located downstream. The factory is making an economically rational decision (from its private perspective) when deciding to dispose of its toxic waste into the river. It is weighing up the private marginal costs against the private marginal benefits. Often, water use has a private marginal cost of zero, which means that a firm will continue to use it right up to the point where its private marginal benefit is zero. That is why resources that are free at the point of use have a tendency to be overexploited. The social cost of disposing of harmful waste into the river, however, is not zero. It is the sum of the external costs on all downstream users, which might include the cost of health problems caused to those drinking and washing in the water downstream, the loss of income in terms of damage to livestock or fish populations, and the cost of reduced biodiversity. Some of these external costs are already valued in monetary terms, but others are not. All, however, reduce the utility of downstream users or increase their production costs. The socially optimal rate of waste disposal into the river is much lower than the rate achieved through a free market. Regulations on what discharges are permissible into a river are an attempt to move from the private market outcome to the socially optimal outcome, making the factory internalise the externality. 4.2. Positive externalities, e.g., soil stabilisation Imagine a mountain village that is concerned about its supply of firewood, which has been rapidly depleting as the village population has grown, therefore necessitating longer journeys to fetch wood and the use of less suitable species, which do not burn as well. To try to tackle this problem, members of the village become involved in a programme of management of the surrounding trees and vegetation, developing a tree nursery and planting out the seedlings. In the foothills of the mountains, there is another village that also benefits from the treeplanting programme. As vegetation cover was reduced in the mountains, this village had suffered from more frequent flooding of the river that runs close to the village, causing considerable soil erosion. The planting programme in the mountains will stabilise the soil and reduce the risk of flooding in the foothills. The mountain village is making its decision to undertake a planting programme by weighing up the costs and benefits to its own members. These private costs involve establishing the nursery and the management of trees that would be planted; the private benefits involve the savings in the amount of time spent in collecting firewood and the better quality of wood that would be available. It does not, however, include the additional (external) benefits to the 11 foothill village. The socially efficient outcome would take this into account, leading to more tree-planting than the private market outcome. 4.3. Public goods, e.g., agricultural research Many governments support programmes of agricultural research. For example, research may investigate which crops are most suitable for which situation, what the response of crops is to different levels of inputs, what the impact of different rotations is, how to improve animal health, eradicate pests and diseases, and how to breed animals that are more productive. Is agricultural research an example of a public good? How do the benefits to society compare with the benefits to private individuals? If one farmer benefits from the research, does that mean other farmers must benefit too? That is, is agricultural research nonexcludable? If one farmer benefits, does this reduce the benefit to another farmer? That is, is agricultural research rival or non-rival? As you will have realised, it depends on the exact nature of the research. Using a higher yielding seed can bring private benefits that outweigh the private cost of buying it. However, these private benefits may not be sufficient to cover the costs of actually developing the new variety, if it is not already available. In these circumstances, a private firm might develop a new variety if it can patent it and then recoup the costs of developing it by selling it to a number of farmers. Thus, some farmers can be excluded from gaining the benefits of the new seed. Alternatively, there may be research into the impacts of obtaining two crops from one area of land. The effects in terms of higher yields may be obvious, so that all farmers can see and benefit from this new knowledge. It would not be possible to exclude some. Therefore, this will discourage private companies from undertaking such research, as they will not be able to profit from selling this knowledge. Such research is still worthwhile, however. The benefits to society in terms of higher yields may easily outweigh the costs of undertaking the research. Without government intervention to provide such research, though, it may never be started. 4.4. Poorly-defined property rights, e.g., access to land Externalities can be seen to result from situations within which property rights are not complete. They are often related to cases where property rights are poorly-defined, where it is not clear who has and who does not have the right to the benefits from a resource and what the limits on the use of that resource are and who is responsible for any associated costs. For example, in the previous example on water pollution, the problem lies with the factory assuming the right to pollute the river with its waste, without taking into account the right of the people located downstream to have unpolluted water. The mountain village ignores the rights of the foothill village not to suffer from soil erosion and flooding. If in each case the external party had a clearly defined property right, they could ensure by legal or social sanction that their rights are taken into account. It remains an externality, because such rights are not clearly defined or easily enforced. Market failure is particularly prevalent, therefore, whenever property rights are poorly defined. Some resources, that are open to access by all, have no property rights defined at all. 12 An example is a piece of land used for grazing by anyone: all can use it and no one person has the right to prevent anyone else from using the land. Each grazier who puts cattle on the land makes a decision about his or her private returns compared to the private costs. For an individual, increasing the number of grazing animals brings the benefits of more meat to sell. It also, however, adds to greater grazing pressure, leading to more soil erosion and lower quality feed. Much of the cost of overgrazing is an external cost, borne by the other graziers, not by the grazier who put on the extra cattle. The benefits accrue to the individual, but the costs are shared among all the graziers. This means that in an open access situation, all graziers have an incentive to keep more animals than is socially optimal, as the decision is made without taking into account the external cost on the other graziers. One solution to externalities such as this is to define some property rights. In this case, it might be necessary to develop mechanisms for excluding some people from access to the resource, or to limit their use of it. This will be discussed in greater detail in Week 3. 4.5. Short-term thinking, e.g., tree planting An important trade-off in the management of our natural resources is the decision about the amount of resources that we should use now and how much we should save for future generations. This can be seen as a particular type of externality, where the effect on the third party of a private economic decision is not felt simultaneously, but in the future. As with all externalities, the market will encourage us to weigh up the private benefit against the private cost. We will take into account future costs and benefits through discounting, which is discussed elsewhere in this course. However, future costs and benefits will only be included as far as they impact on the agent involved in the management decision. The cost or benefit to, for example, somebody else’s children (i.e. external cost or benefit) may well be ignored,. An example of this type of externality would be where a decision needs to be made about the amount of resources that has to be put into planting trees. A private owner of land would weigh up the private discounted costs of planting the trees against the private discounted benefits of selling timber at some later date. As it will take a number of years for the trees to grow and mature, the benefits may appear relatively small in present value terms compared to the costs. Thus, this might lead to no new planting at all, giving rise to a considerable external cost on future generations, who will find it difficult to find sufficient timber for their needs. The private market solution may be a result of a short-term perspective, and therefore would not put sufficient weight on future costs and benefits. Society as a whole may put more weight on the future and so the efficient allocation of resources would take into account a long-term perspective. What weights to put on the potential preferences of future generations and how to implement this in practice is not clear, and this is a major concern within the sustainability debate. 5. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS In this chapter we have learnt that markets can be an efficient way of allocating resources. This depends on there being prices for the goods or services, an effective mechanism for transmitting those prices and sufficient competition within the market. However, markets 13 may fail to allocate resources for the benefit of society as a whole in a number of situations. If there is a lack of competition, firms may not respond to the preferences of consumers. If there are high transaction costs, the information may not be available for suppliers to respond to changes in demand, or for consumers to respond to changes in supply. In relation to the management of natural resources, the most important market failure is when there are unmarketed and unpriced goods and services. This is the case when there are externalities and public goods. Individuals and firms would make management decisions in response to the private costs and benefits they face, rather than take into account the total social costs and benefits. Much of the remainder of this course will deal with ways to correct for the failure of the market to allocate non-priced goods. A range of techniques can be used to estimate the value of non-marketed goods and services. The government can then intervene in the market through, for example, taxes and subsidies to alter the price signals to which producers and consumers respond, which would make the producers and consumers ‘internalise’ their externalities. 6. REVIEW QUESTIONS Exercise 10: The following are problems that cause market failures: i. Externalities ii. Monopoly / oligopoly power iii. Monopsony / oligopsony power iv. Ignorance and uncertainty v. Public goods and services vi. Persistent disequilibria vii.Dependants viii.Merit goods Match each of the above problems to the following examples of failures of the free market. In each case assume that everything has to be provided by private enterprise: that there is no government provision or intervention whatsoever. Note that there may be more than one example of each problem. Also each case may be an example of more that one market problem. Which Market Failure? There is an inadequate provision of street lighting because it is impossible for companies to charge all people benefiting from it Advertising allows firms to sell people goods that they do not really want A firm tips toxic waste into a river because it can do so at no cost to itself 14 Firms pay workers less than their marginal revenue product Prices take some time to adjust to changes in consumer demand People may not know what is in their best interest and thus may underconsume certain goods or services, such as education Firms’ marginal revenue is not equal to the price of the good and thus they do not equate MC and price Firms provide an inadequate amount of training because they are afraid that other firms will simply come along and ‘poach’ the labour they have trained In families one person may do the shopping for everyone and may buy things that other family members do not like Farmers cannot predict the weather Minimum efficient scale is at 58% of current industry output Exercise 11: Would it be desirable for all pollution to be prevented? Explain your answer using an example and a diagram. Exercise 12: Consider your activities during a day. • What external costs and benefits resulted from your activities? Try and identify all externalities you created. • Were there any pressures on you to avoid generating external costs? If so, were these pressures social, moral or what? • How could you best be encouraged / persuaded / forced to take the externalities fully into account? Are there any costs in such methods? Exercise 13: Go back to your examples of natural resources that are not marketed, from Exercise 1. Discuss with your neighbour whether these resources are being managed in a socially efficient way and whether there is any evidence of market failure. 7. ANSWERS TO EXERCISE 10 There is an inadequate provision of street lighting because it is impossible for companies to charge all people benefiting from it 15 Which Market Failure? v Advertising allows firms to sell people goods that they do not really want iv, ii A firm tips toxic waste into a river because it can do so at no cost to itself i Firms pay workers less than their marginal revenue product Prices take some time to adjust to changes in consumer demand iii, iv vi People may not know what is in their best interest and thus may underconsume certain goods or services, such as education viii, iv Firms’ marginal revenue is not equal to the price of the good and thus they do not equate MC and price ii Firms provide an inadequate amount of training because they are afraid that other firms will simply come along and ‘poach’ the labour they have trained i In families one person may do the shopping for everyone and may buy things that other family members do not like vii, ii Farmers cannot predict the weather iv Minimum efficient scale is at 58% of current industry output ii REFERENCES Two very useful general collections of environmental economics are: Daly, H.E. and Townsend, K.N. (eds.). (1993). Valuing the Earth: Economics, Ecology and Ethics. MIT Press. Markandya, A. and Richardson, J. (eds.). (1992). The Earthscan Reader in Environmental Economics. Earthscan, London. Further reading on Market structures and imperfect competition can be found in most economics textbooks. Transaction costs can be found in: Williamson, O.E. (1996). The Mechanisms of Governance. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Externalities and public goods can be found in all environmental economics texts, such as: Field, B.C. (1994). Environmental Economics: An Introduction. McGraw-Hill, New York. Hanley, N., Shogren, J.F. and White, B. (1997). Environmental Economics in Theory and Practice. Macmillan, Basingstoke. Pearce, D.W. and Turner, R.K. (1990). Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment. Harvester Wheatsheaf, Hemel Hempstead. 16 Perman, R., Ma, Y. and McGilvray, J. (1996). Natural Resource and Environmental Economics. Longman, London. Tietenberg, T.H. (1994). Environmental Economics and Policy. Harper Collins. Tietenberg, T.H. (1992). Environmental and Natural Resource Economics. Harper Collins, New York. Tisdell, C.A. (1993). Environmental Economics: Policies for Environmental Management and Sustainable Development. Edward Elgar, Aldershot. Turner, R.K. (1993). Sustainable Environmental Economics and Management: Principles and Practice. Wiley, Chichester. Turner, R.K., Pearce, D.W. and Bateman, I. (1994). Environmental Economics: An Elementary Introduction. Harvester Wheatsheaf, Hemel Hempstead. Methods for correcting for market failure are discussed in: Hanley, N. and Spash, C.L. (1993). Cost Benefit Analysis and the Environment. Edward Elgar, Aldershot. Pearce, D.W., Markandya, A. and Barbier, E.B. (1989). Blueprint for a Green Economy. Earthscan, London. Pearce, D.W. (1993). Blueprint 3: Measuring Sustainable Development. Earthscan, London. Pearce, D.W. (1995). Blueprint 4: Capturing Global Environmental Value. Earthscan, London. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (1994). Managing the Environment: the role of economic instruments. OECD, Paris. Taylor, R. (1992). The Market in Environment: Market Failure or Market Solutions? ASI Research Ltd, London. Property rights can be found in: Anderson, T.L. and Leal, D.R. (1991). Free Market Environmentalism. Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy, San Francisco. Bromley, D.W. (1991). Environment and Economy: Property Rights and Public Policy. Basil Blackwell, Oxford. Bromley, D.W. (1997). Property regimes in environmental economics. In H. Folmer and T. Tietenberg (eds.). The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 1997/98. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham. 1-27. 17 Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the commons. Science 162(13): by Janet Egdell Department of Agriculture University of Aberdeen 581 King Street Aberdeen, United Kingdom AB24 5UA E-mail: j.egdell@abdn.ac.uk 18 19 Figure F. Edgeworth Box Illustrating Negotiation over a Negative Externality 20 Figure G. Optimal Provision of a Public Good Q1 Q2 21