0008_Chapter 1_9780240810690.indd

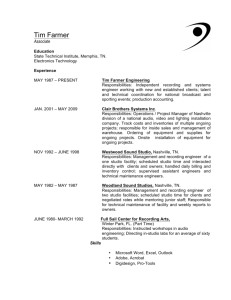

advertisement