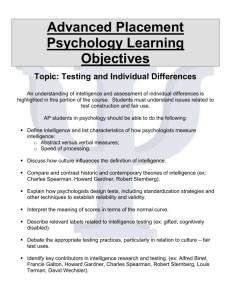

chapter 8 chapter 8 intelligence intelligence

advertisement

Chapter six - 1 CHAPTER 8 INTELLIGENCE “I believe that it is the standard definition of intelligence that narrowly constricts our view, treating a certain form of scholastic performance as if it encompasses the range of human capacities and leading to disdain for those who happen not to be psychometrically bright” (Gardner, 1996, p. 205). “The function of education is to create human beings who are integrated and therefore intelligent . . . Intelligence is the capacity to perceive the essential, the what is; and to awaken this capacity, in oneself and in others, is education” (Indian philosopher, Jiddu Krishnamurti said, 1953 p. 14). “There is no correspondence between an IQ score and the size or functioning efficiency of the brain or any particular part of it, and there is no single ability that we can call intelligence” (Good & Brophy, 1995, p. 516). We know that intelligence is important. Most people would rather have more of it than less of it. But what exactly is it? Is it the ability to produce high scores on intelligence tests? Is it the ability to earn good grades? Is it the ability to remember information? Is it the ability to process numbers quickly? Or perhaps it is the ability to learn how to play musical instruments, speak different languages, play different sports, win at poker, solve puzzles, create new inventions, make money, or figure out how to operate computer programs? Cyril Burt (1957), a British educational psychologist (1883-1971) defined intelligence as innate cognitive ability. We know that cognition means thinking, so it would be one’s inborn (innate) ability to think. But what should one think about? How exactly should one think? Is there a particular way of thinking that is better than another? An Internet search using the term ‘intelligence’ will provide many different definitions. Before reading further you may want to see if you can find two or three that make sense to you. Check also to see if your definition or conception of intelligence changes by the time you finish reading this chapter. DEFINING INTELLIGENCE: TRADITIONAL VIEWS This section examines traditional definitions or a psychometric view of intelligence. Alfred Binet The idea of quantifying or describing intelligence with a number started with Alfred Binet back at the turn of the last century. In 1904 he was hired by the French minister of public instruction to help them identify children who seemed unable to learn at an average rate in their public schools. Once identified, these children were to be sent to alternative schools where they would receive special help appropriate to their needs. Binet had to find a way to determine which students were within the normal range of intellectual functioning and which were below the normal range. He came up with a test that was to measure intelligence: the intelligence quotient test or IQ test. The IQ Score The Binet’s IQ score was originally calculated using a ratio (ratio IQ) using the following steps: First, students would take a test that contained a set of questions, problems, and logical thinking puzzles. Next, their test scores were compared to the average test score and age of all students who had taken the test. Then, a student’s mental age was determined by finding the average age of students who had a similar test score. For example, if a student’s test score was that same as the average score of all 10 year olds this would be that student’s mental age. The chronological age is how old the student is in years. Finally, the IQ score was computed by dividing students’ mental age by their chronological age and multiplying by 100 (IQ ‘ MA/CA x © Andrew Johnson, Ph.D. Minnesota State University, Mankato www.OPDT-Johnson.com Chapter six - 2 100). For example, if a child scored at the 10 year old average (MA) and was 7 years old (CA), the IQ score would be 10 divided by 7 (1.42) multiplied by 100 for an IQ score of 142. However, if another child scores at the 10 year old average (MA) and was 14 years old (CA), the IQ score would be 10 divided by 14 (.71) multiplied by 100 for an IQ score of 71. One problem with this approach was that mental age scores level off by the time students are around the age of 15 or 16 (Eysenck, 1994). The mental age of a 16 year old is not much different than that of a 17 year old. The problem is even more pronounced when you try to compare the mental age of a 48 year old versus a 49 year old. Thus, while ratio IQ worked somewhat for children it was inaccurate for people over 15 years of age. In 1916, Stanford psychologist Lewis Terman refined the Binet-Simon intelligence scale. His work is the basis for today’s Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale. Instead of a strict ratio, standard deviation (deviation IQ) was used to compare people of the same age or category across a normal distribution. A normal distribution means that if you chose a large sample of people at random, their test scores (or any other kinds of scores) would look like the bell-shaped pattern in Figure 8.1. (The horizontal axis represents students’ test scores going from lowest to highest; the vertical axis represents the number of students who obtained each score.) It is normal (hence normal distribution), to have a whole bunch of students at the average range and it is also normal to have very few students at the very high end and very low end. You can see that the greatest number of individuals scored right in the middle. That is average. A score of 100 would be the absolute average score. Scores are determined, not by the ratio; but by how far they deviate from the average. IQ scores of 85-115 are considered to be within the average range. 68% of the populations fall within this range. Table 8.2 contains a descriptive classification of IQ scores. Figure 8.1. Bell shaped curve. Table 8.2. Descriptive classifications of IQ scores. IQ 128+ 120-127 111-119 91-110 80-90 66-79 Below 65 © Andrew Johnson, Ph.D. Minnesota State University, Mankato www.OPDT-Johnson.com Description % of Population - very superior -2.2% - superior -6.7% - high average -16.1% - average -50% - low average -16.1% - borderline -6.7% - extremely low -2.2% Chapter six - 3 Fallacy of Numbers According to a psychometric view above, intelligence is the entity or ability that is measured on tests. While it is comforting to have a precise description of intelligence like this, attaching a number to something does not make it any more real. Robert Sternberg (1996) describes some of the problems associated with IQ tests as follows: 1. They represent a very narrow range of thinking. Who decided what types of problems were to be on these intelligence tests? Who determined which type of thinking was important? The problems found on these tests tend to rely on only logical-deductive or analytic thinking; they do not represent the variety of types of thinking that is used in real life situations to solve problems or create products and performances. 2. They are highly dependent on vocabulary and exposure to concepts. You could have a high functioning brain, but if, because of environmental situations, you have not been exposed to certain words, concepts, or thinking strategies your ability to score well is greatly diminished even though your low score would have nothing to do with your ability to think. 3. They have little predictive value. The biggest predictor of these tests is your ability to do equally well on a similar test. There may be some correlation with school grades or school-based performance, but there is little correlation with success in the real world. 4. They do not measure creative or practical thinking abilities. The ability to generate ideas and to apply ideas in the real world are every bit as important in achieving most types of success as analytical thinking. Charles Spearman’s Two-Factor Theory of Intelligence Charles Spearman (1863-1945) was a British psychologist who took a psychometric view of intelligence. He proposed a “two-factor” theory of intelligence. According to him, there were two factors that made up intelligence: The first factor was called ‘g’ or general intelligence. This can be thought of as your brain’s general processing capabilities, a type of intelligence that could be applied to many types of tasks. Using a computer analogy, this would be the amount of memory that can be used to process a variety of different tasks. If you have more of it (memory), you can process many things quickly. The second factor was called ‘s’ or specific intelligence which were the types of intelligence involved in a specific task such as math, writing, or vocabulary activities. Spearman thought that true intelligence was related only to the ‘g’ factor. Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence. John Horn and Raymond Cattell (1966) are known for their work related to fluid and crystallized intelligence. Fluid intelligence, is somewhat related to Spearman’s concept of ‘g’. It is the brain’s general processing power or the ability to process, apply, and manipulate data (both internal and external), as well as the ability to adapt to circumstances and recognize patterns. According to them fluid intelligence tends to decrease slightly with age. Crystallized intelligence is one’s accumulated knowledge. This includes declarative knowledge such as vocabulary, basic information, and concepts; and also procedural knowledge such as processes, thinking skills, pattern recognition, and problem solving strategies (see Chapter 8 for types of knowledge). This type of intelligence tends to increase with age. Thus any decrease in fluid intelligence is offset by increases in crystallized intelligence. Using a Michael Jordan analogy, fluid intelligence can be compared to Jordan’s athletic ability; the ability to jump, run, lift things, and one’s flexibility and overall endurance and physical capacity. When he first entered the NBA he was a phenomenal athlete at the peak of his physical capacity. He could run, jump, and move better than anybody in the league. His raw physical capacity is a metaphor for one’s raw, neurological capacity. However, for all his athletic ability, Michael Jordan wasn’t the best basketball player in the league at this point. Over time he learned strategies, various moves, different shots, and how and when to pass. His knowledge of the game and situations enabled him to process data microseconds quicker and make better decisions. He began to see the game three and four steps ahead of other players. This knowledge and his various strategies are a metaphor for one’s crystallized intelligence. Even though Jordan’s physical abilities began to decline in his early 30s, his knowledge and strategies continued to increase. He was probably at his peak in his mid 30s. But unlike intelligence, one’s repertoire of knowledge and strategies in sports cannot offset © Andrew Johnson, Ph.D. Minnesota State University, Mankato www.OPDT-Johnson.com Chapter six - 4 one’s diminishing physical capacity. Even thought Michael Jordan did play at a high level for a very long time, he eventually retired for the final time at age 40. DEFINING INTELLIGENCE: EXPANDED VIEWS This section presents theories of intelligence that describe people not as more intelligent or less intelligent; rather, as intelligent in different ways. For example, the type of intelligence necessary to be an effective teacher in a first grade classroom is much different than that of a scientist working on complex research project at a university. The type of intelligence valued and displayed by Mia Hamm on a soccer field is different than that of J.K Rowling writing books, John Stewart creating comedy, or B.B. King playing a blues solo on his guitar. Each domain values different traits and each utilizes a different type of thinking to achieve mastery. Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences Howard Gardner’s book Frames of Mind (1983) was instrumental in getting schools to start thinking about intelligence in much broader terms. He defined intelligence as the ability to solve problems or create products which are valued within a culture setting. Instead of a single entity with many facets, Gardner identified eight different kinds of intelligences (Checkley, 1997): 1. Linguistic intelligence is the ability to use words to describe or communicate ideas. Examples -poet, writer, storyteller, comedian, public speaker, public relations, politician, journalist, editor, or professor. 2. Logical-mathematical intelligence is the ability to perceive patterns in numbers or reasoning, to use numbers effectively, or to reason well. Examples -- mathematician, scientist, computer programmer, statistician, logician, or detective. 3. Spatial intelligence is the ability to perceive the visual-spatial world accurately (not get lost) and to transform it. Examples -- hunter, scout, guide, interior decorator, architect, artist, or sculptor. 4. Bodily-kinesthetic intelligence is expertise in using one’s body. Examples -- actor, athlete, mime, or dancer. 5. Musical intelligence is the ability to recognize and produce rhythm, pitch, and timber; to express musical forms; and to use music to express an idea. Examples -- composer, director, performer, or musical technician. 6. Interpersonal intelligence is the ability to perceive and appropriately respond to the moods, temperaments, motivations, and needs of other people. Examples -- pastor, counselor, administrator, teacher, manager, coach, co-worker, or parent. 7. Intrapersonal intelligence is the ability to access one’s inner life, to discriminate one’s emotions, intuitions, and perceptions, and to know one’s strengths and limitations. Examples -- religious leader, counselor, psychotherapist, writer, or philosopher. 8. Naturalistic intelligence is the ability to recognize and classify living things (plants, animals) as well as sensitivity to other features of the natural world (rocks, clouds). Examples -- naturalist, hunter, scout, farmer, or environmentalist. So how is a teacher supposed to use Gardner’s theory? Two ideas: First, let students know that there are different ways to be smart and that it is okay to be good at some things and not good at others. As Robert Sternberg (1996) says, almost everybody’s good at something; almost nobody’s good at everything. Many classrooms teachers put up posters describing each of these types of intelligence. Some even expand this by asking students to think of other ways to be smart and then let them create additional posters. Second, in your future classroom, design learning experience, activities, and assignments that use these different ways of thinking. Try to incorporate the varied types of intelligence into your lessons and units (not always possible). By using these different ways of thinking to manipulate subject matter content students will see things from a broader perspective, learn more, and learn more deeply (Diaz-Lefebvre, 2006; Kornhaber, 2004). Spiritual Intelligence Gardner has considered a 9th intelligence: Existential intelligence (1999). This would be a trait related to © Andrew Johnson, Ph.D. Minnesota State University, Mankato www.OPDT-Johnson.com Chapter six - 5 spiritual intelligence and concerned with issues regarding the nature of existence and ultimate issues. However, it does not meet his requirements for an intelligence and thus, he has not included in his list. But others have explored this area. Sisk and Torrance (2001) describe Spiritual Intelligence as the ability to use a multi-sensory approach to problem solving and the ability to listen to your inner voice. Zohar and Marshall (2001) describe it as “… the intelligence with which we address and solve problems of meaning and value, the intelligence with which we can place our actions and lives in a wider, richer, meaning-giving context, the intelligence with which we can assess that one course of action or one life-path is more meaningful than another” (pp 3-4). Vaughan (2003) portrays spiritual intelligence as a different way of knowing, a part of self that is concerned with the life of the mind and spirit and its relationship to being in the world. For the purpose of this book, spiritual intelligence will be defined here as the ability to become attuned to and utilize multiple dimensions of self; and to perceive and experience the seamless connection between self, others, and the universe. Spiritual intelligence is a concept you are not likely to encounter in any formal way in a public school setting. So why include it here? There are dimensions of the human experience that cannot be measured or quantified yet still play a prominent role in helping many people solve problems, make decisions, and come to know the world. A study of humans and human learning should take into account all dimensions of the human experience. Sternberg’s Triarchic Theory of Intelligence Robert Sternberg (1985) defines intelligence as the ability to adapt to and shape one’s environment to meet one’s needs or purposes. His Triarchic Theory of Intelligence (Sternberg & Williams, 2002), describes three types of thinking that are used together to meet this end: Creative or generative thinking. You are able to generate many ideas, synthesize two or more ideas, create original ideas, think outside the box, find ideas that nobody else has considered, or utilize divergent thinking and inductive reasoning. Analytical or evaluative thinking. You are able to evaluate ideas, analyze ideas, organize ideas, compare ideas, or utilize convergent thinking and deductive reasoning. Pragmatic thinking. You are able to implement, apply, or adapt the ideas produced through generative and evaluative thinking to meet the demands of your particular situation. According to Sternberg’s theory, intelligence can be found in any domain. For example, intelligence related to teaching would be the ability to use all three of these types of thinking to create effective learning experiences. An intelligent teacher would be able to (a) generate ideas for creating new learning experiences and solving problems related to teaching and learning; (b) evaluate and organize those ideas; and then (c) adapt and apply them to his or her particular setting. This view is helpful because it describes three broad thinking processes that can then be applied to any areas. Sternberg (1996) also supports that idea that intelligence is not a fixed entity; rather, it is something that can be improved by teaching problem solving strategies, thinking skills, and other types of cognitive strategies. Successful Intelligence Sternberg also describes what he calls successful intelligence which he defines as “… an integrated set of abilities used to attain success in life, however a person chooses to define success or however it might be defined within a particular sociocultural context” (Sternberg & Grigorenka, 2000, pg 6). Depending on what you value or your culture values, success might include one or more of kinds of accomplishments listed in Figure 8.3. Figure 8.3. Different types of accomplishments. © Andrew Johnson, Ph.D. Minnesota State University, Mankato www.OPDT-Johnson.com Chapter six • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 6 healthy relationships and family life. creative artistic freedom and expression. happiness, peace of mind. an accumulation of wealth or material possessions. accomplishments: athletic, artistic, scholarly, business, political, scientific, etc.. power and importance. fame and prestige. honor, integrity, and truthfulness. the ability to give to and nurture. free time, freedom, and a lack of responsibilities. developing or running a successful business or some other type of enterprise. wisdom. wholeness, spiritual gifts. Leadership roles. Sternberg (2003) describes three characteristics shared by successfully intelligent people: 1. Successfully intelligent people recognize their strengths and use them to compensate for their weakness. Would you try to teach a one-handed person to clap? Too often in schools we attempt to do just that. Students are described in terms of what they can not do. Their weaknesses are identified and overemphasized in an attempt to remediate them. Instead, time might be better spent teaching students how to use their strengths to compensate for or correct weaknesses. 2. Successfully intelligent people are able to adapt to, shape, and select their environments. Polly moved in with Samantha. She soon found out that Samantha was messier than she had imagined. One trait in particular that particularly bothered Polly was the fact that Samantha always left dirty dishes in the sink. To adapt to her environment, Polly could tell herself that it really did not matter. She might also start eating most of her meals outside the apartment. To shape her environment she could talk with Samantha. She could create a chart and assign dishwashing days. Or she could hide every dish except one pot and pan, and two plates, dishes, cups, and sets of silverware. To select a new environment Polly could try to get out of her lease or look for a less messy roommate to trade places with. 3. Successfully intelligent people are able to use analytical, creative, and practical thinking to create products or performances, to solve problems, or to achieve their goals. To illustrate this idea, look at the teaching example described above under triarchic intelligence theory. “We must never lose sight of the fact that what really matters most in the world is not inert intelligence but successful intelligence: that balanced combination of analytical, creative, and practical thinking skills. Successful intelligence is not an accident; it can be nurtured and developed in our schools by providing students, even at an early age, with curricula that will challenge their creative and practical intelligence, not only their analytic skills” (Sternberg & Grigorenka, 2000, pg 269). PASS Theory of Intelligence The PASS theory describes intelligence by considering how problems are solved and information is processed during learning (Fein & Day 2004; Naglieri & Kaufman 2001). That is, intelligence is the ability to use four interdependent cognitive processes or ways of thinking together when confronted with a task, a problem, or a learning situation. These processes are: planning, attention, simultaneous processing, and successive processing. And like Sternberg’s triarchic theory of intelligence, these four processes can be applied to any domain. Planning. When confronted with a task or problem you are able to select an appropriate strategy from your repertoire of problem solving strategies, apply it, and evaluate it as you are using it. © Andrew Johnson, Ph.D. Minnesota State University, Mankato www.OPDT-Johnson.com Chapter six - 7 Attention. While you are working on a task or problem you are able to select and focus on important stimuli while tuning out irrelevant stimuli. You can maintain focused attention in pursuit of a task or in the accomplishment of a goal without getting districted. Simultaneous processing. While working on a task or problem you are able to process information simultaneous in order to integrate separate bits of information into an organized whole. Successive processing. While working on a task or problem you are able to arrange information in a defined order. Goleman’s Theory of Emotional Intelligence The last type of intelligence considered here is emotional intelligence (EI). This is a type of social intelligence somewhat related to Gardner’s conception of intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligence above. It is the ability to perceive and understand emotions, manage one’s emotion, monitor one’s own and others' emotions, and to use that information to guide one’s thinking and actions (Goleman, 1995; Pfeiffer, 2000). EI involves abilities that can be categorized into five domains (see Figure 8.4). Figure 8.4. Emotional intelligence. • Self-awareness: Observing yourself and recognizing a feeling as it happens (intrapersonal intelligence). • Managing emotions: Handling feelings so that they are appropriate; understanding the origin of emotions; finding ways to handle negative emotions (fears, anxieties, anger, and sadness). • Motivating oneself: Channeling emotions in the service of a goal; ability to delay gratification and stifle impulses to obtain a greater goal. • Empathy: Sensitivity to others' feelings and concerns and taking their perspective; ability to appreciate the differences in how people feel about things. • Handling relationships: Managing emotions in others; social competence and social skills. The five domains described in Figure 8.4 can all be addressed within a general education curriculum. For example, we can teach students to identify and become more aware of their own emotions and inner worlds (self-awareness). We can teach them to manage their emotions by helping them discover healthy responses to their feelings of angry, anxiety, sadness, or other emotions. We can help students define goals for themselves and to describe the steps necessary to achieve those goals. And we can also help students develop empathy and to learn how to handle a variety of types relationships. It is very appropriate then that these elements be included in our curriculums, not as separate curriculum item; rather, embedded into social studies, health, literature, and other curriculum areas. CONCLUDING THOUGHTS This chapter provided a sense of the traditional, psychometric views of intelligence as well as insight into other possible dimensions of intelligence. Intelligence is certainly much more than a little number. However, after all that has been written on multiple views of intelligence in the last years, most schools still rely solely on quantitative data from standardized achievement or ability tests to define both intelligence and achievement. This practice fails in helping to develop the potentials of those students who talents and ways of thinking fall outside the narrow definitions imposed upon them by schools. © Andrew Johnson, Ph.D. Minnesota State University, Mankato www.OPDT-Johnson.com Chapter six - 8 Summary of Key Ideas • The first intelligence test was developed in France in 1904 to identify those children who would not benefit from traditional schooling. • Traditional intelligence tests measure a very narrow range of thinking. • Charles Spearman proposed that intelligence was made up of two factors: general intelligence and then specifics types of intelligence. • According to Horn and Cattell, fluid intelligence is the brain’s general processing power and crystallize intelligence is an accumulation of one’s knowledge and cognitive strategies. • Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences identifies eight different types of intelligence: linquistic, logical-mathematical, visual-spatial, interpersonal, intrapersonal, musical, bodily-kinesthetic, and naturalistic. • Robert Sternberg’s Triarchic Theory of Intelligences posits that intelligence can be found in any domain and consists of three types of thinking: generative, analytic, and pragmatic. • Successful intelligence is an integrated set of abilities that are used to attain success in life. • The PASS Theory describes intelligence as the ability to use four cognitive processes to solve problems: planning, attention, simultaneous processing, and successive processing. • Emotional intelligence is the ability to perceive and understand emotions, manage one’s emotion, monitor one’s own and others' emotions, and to use that information to guide one’s thinking and actions References Burt, C. (1957). The causes and treatments of backwardness (4th ed.). London: University of London Press. Checkley, K. (1997). The first seven ... and the eighth: A conversation with Howard Gardner. Educational Leadership, 55, 8-13. Eysenck, H. (1994). Test your IQ. Toronto: Penguin Books. Fein, E.C. & Day, E.A. (2004). The PASS theory of intelligence and the acquisition of a complex skill: A criterion-related validation of study of Cognitive Assessment System Scores. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 1123-1136. Gardner, H. (1996). Reflection on multiple intelligence: Myths and messages. Phi Delta Kappan, 77, 200-209. Gardner, H (1999) Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century. New York. Basic Books. Goleman, D. (1994). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books. Good, T., & Brophy, J. (1995). Contemporary educational psychology (5th ed.). White Plains, NY: Longman Horn, J.L. & Cattell, R.B. (1966). Refinement and test of the theory of fluid and crystallized general intelligences. Journal of Educational Psychology (57), 253-270. Krishnamurti, J. (1953). Education and the significance of life. San Francisco, CA: HarperCollins. Naglieri, J. & Kaufman, J. (2001). Understanding intelligence, giftedness, and creativity using PASS theory. Roeper Review, 23, 151-156. Pfeiffer, S. (2000). Emotional intelligence: Popular but elusive construct. Roeper Review, 23, 138-142. © Andrew Johnson, Ph.D. Minnesota State University, Mankato www.OPDT-Johnson.com Chapter six - 9 Sisk, D. & Torrance, E.P. (2001). Spiritual intelligence: Developing higher consciousness. Buffalo, NY: Creative Education Foundation Press. Sternberg, R. J. (1985). Beyond IQ: A Triarchic Theory of Intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Sternberg, R. (1996). Successful intelligence: How practical and creative intelligence determine success in life. New York: Plume. Sternberg, R. J. (2003). A broad view of intelligence: A theory of successful intelligence. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 55, 139-154. Sternberg, R.J. & Grigorenka, E. (2000). Teaching for successful intelligence. Arlington Heights, IL: Skylight Professional Development. Vaughan, F. (2003). What is spiritual intelligence? Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 42, 16-33. Zohar, D. & Marshall, I. (2000). Connecting with our Spiritual Intelligence. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing © Andrew Johnson, Ph.D. Minnesota State University, Mankato www.OPDT-Johnson.com