The Church for Disciples of Christ: Seeking to be Truly Church Today

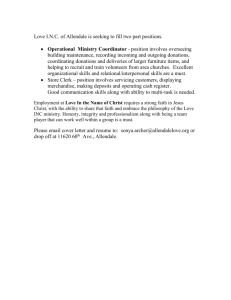

advertisement