From the Carter to the Bush Doctrine

advertisement

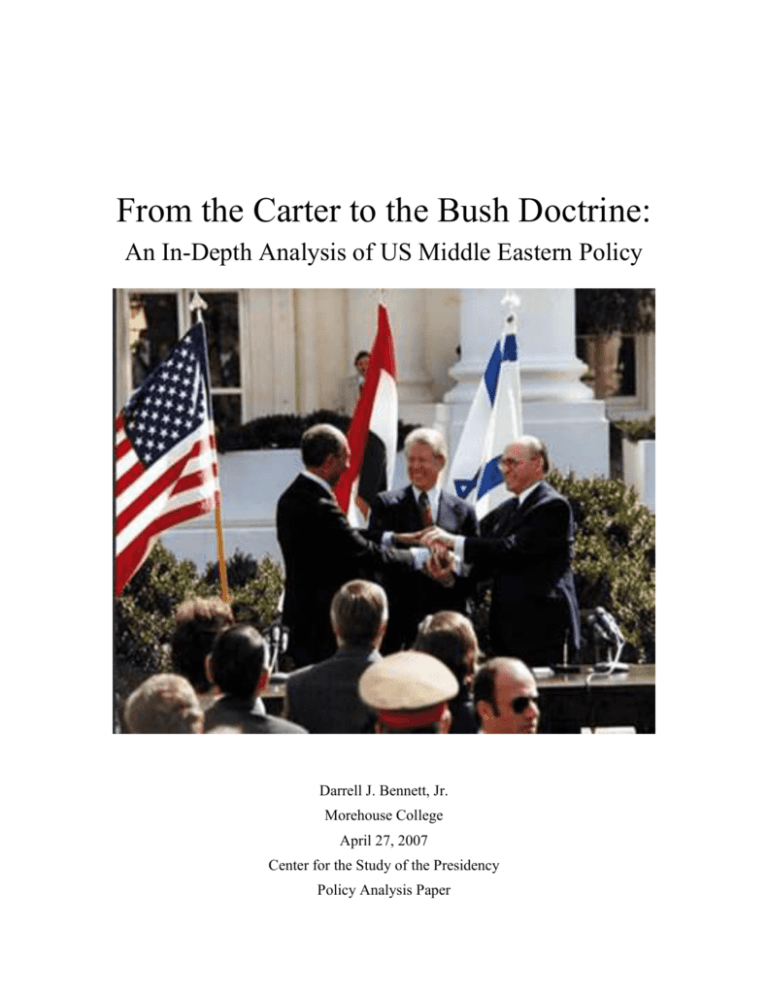

From the Carter to the Bush Doctrine: An In-Depth Analysis of US Middle Eastern Policy Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. Morehouse College April 27, 2007 Center for the Study of the Presidency Policy Analysis Paper Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. Table of Contents Paper------------------------------------3 Bibliography---------------------------13 Appendixes-----------------------------15 2 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. The Carter Doctrine was a policy proclaimed by President of the United States Jimmy Carter in his State of the Union Address on January 23, 1980, which stated that the United States would use military force if necessary to defend its national interests in the Persian Gulf region. The doctrine was a response to the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union, and was intended to deter the Soviet Union—the Cold War adversary of the United States—from seeking hegemony in the Gulf. After stating that Soviet troops in Afghanistan posed "a grave threat to the free movement of Middle East oil," Carter proclaimed: Let our position be absolutely clear: An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force. In this, the key sentence of the speech, written by then National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter initiated a policy that would govern our actions in the region for the next 25 years. In this paper I will discuss the impetus for the policy, how it has evolved, its implications and possible alternatives and what the present policy is. The Persian Gulf region was first proclaimed to be of national interest to the United States during World War II. Petroleum is of central importance to modern armies, 3 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. and the United States—as the world's leading oil producer at that time—supplied most of the oil for the Allied armies. Many American strategists were concerned that the war would dangerously reduce the U.S. oil supply, and so they sought to establish good relations with Saudi Arabia, a kingdom with large oil reserves. On February 16, 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said the "the defense of Saudi Arabia is vital to the defense of the United States."1 On February 14, 1945, while returning from the Yalta Conference, Roosevelt met with King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia on the Great Bitter Lake in the Suez Canal, the first time a U.S. president had visited the Persian Gulf region. (During Operation Desert Shield in 1990, this landmark meeting between Roosevelt and King Ibn Saud was cited by Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney as one of the justifications for sending troops to protect Saudi Arabia's border.)2 The Persian Gulf region continued to be regarded as an area of vital importance to the United States during the Cold War. Three Cold War United States Presidential doctrines—the Truman Doctrine, the Eisenhower Doctrine, and the Nixon Doctrine— played roles in the formulation of the Carter Doctrine. The Truman Doctrine, which stated that the United States would send military aid to countries which were threatened by Soviet communism, was used to strengthen the security of Iran and Saudi Arabia. In October 1950, President Harry Truman wrote to King Ibn Saud that "the United States is 1 2 Houghton, 29. Tanter, 9. 4 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. interested in the preservation of the independence and territorial integrity of Saudi Arabia. No threat to your Kingdom could occur which would not be a matter of immediate concern to the United States."3 The Eisenhower Doctrine in turn called for U.S. troops to be sent to the Middle East to defend U.S. allies against their Soviet-backed adversaries. Finally, application of the Nixon Doctrine provided military aid to Iran and Saudi Arabia so that these U.S. allies could ensure peace and stability in the region. The overthrow of Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlevi of Iran by an Islamic revolutionary government earlier in 1979 had led to a steady deterioration in Iran-U.S. relations. In response to the exiled shah's admission (Sept., 1979) to the United States for medical treatment, on November 4, 1979 a crowd of about 500 seized the embassy taking approximately 90 Americans hostage. (52 of those originally taken hostage were kept captive for 444 days until their release in January 1981.) On December 24, 1979, in the same region, the Soviet army invaded Afghanistan. U.S President Jimmy Carter indicated that the Soviet incursion was "the most serious threat to the peace since the Second World War." Carter later placed an embargo on shipments of commodities such as grain and high technology to the Soviet Union from the US. The increased tensions, as well as the anxiety in the West about masses of Soviet troops being in such proximity to oil-rich 3 Harris, 19. 5 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. regions in the Gulf, effectively brought about the end of detente: thawing of the Cold War, occurring from the late 1960s until the start of the 1980s.4 Both the Iranian Revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan prompted the restatement of U.S. interests in the region in the form of the Carter Doctrine, which stated that the Persian Gulf area, because of its oil fields, was of vital interest to the United States, and that any outside attempt to gain control in the area would be "repelled by use of any means necessary, including military force."5 In The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power, author Daniel Yergin notes that the Carter Doctrine "bore striking similarities" to a 1903 British declaration, in which British Foreign Secretary Lord Landsdowne warned Russia and Germany that the British would "regard the establishment of a naval base or of a fortified port in the Persian Gulf by any other power as a very grave menace to British interests, and we should certainly resist it with all the means at our disposal."6 The policy implications of the doctrine were vast. Because the United States did not have significant military capabilities in the Persian Gulf region at the time the Carter Doctrine was proclaimed, it was criticized for being not backed by sufficient force. The Carter administration began to build up the Rapid Deployment Force, which would 4 Farber, 12. Yergen, 327. 6 Ibid., 451. 5 6 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. eventually become CENTCOM. In the interim, the administration expanded the U.S. naval presence in the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. In 1977, a presidential directive called for a mobile force capable of responding to worldwide contingencies but to be established without diverting forces from NATO or Korea. Not until the aftermath of the Iranian revolution in 1979 and the acknowledgment of a Soviet combat brigade in Cuba in that same year, however, did a concerted effort to establish the force envisioned in the directive begin. These events led to President Carter announcing before a television audience on 1 October 1979 the existence of the Rapid Deployment Forces, or RDF. The concept was to develop forces that could operate independently, with neither forward bases nor the facilities of friendly nations; geographical areas cited as requiring such cover included Korea, the Persian Gulf, and the Middle East. Conceived as a force with a global orientation, the RDF soon focused its attention and planning on the Persian Gulf region. The doctrine, along with other events, such as the revolution in Iran and the US hostage stand-off that accompanied it, the Iran-Iraq war, the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the escalating tensions between Pakistan and India, and the rise of Middle Eastborn terrorism against the West, contributed to making the Middle East an extremely turbulent region during the 1980s. 7 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. Carter's successor, President Ronald Reagan, extended the policy in October 1981 with what is sometimes called the "Reagan Corollary to the Carter Doctrine", which proclaimed that the United States would intervene to protect Saudi Arabia, whose security was threatened after the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War, which lasted from 1980 to 1988. Thus, while the Carter Doctrine warned away outside forces from the region, the Reagan Corollary pledged to secure internal stability. According to diplomat Howard Teicher, "with the enunciation of the Reagan Corollary, the policy ground work was laid for Operation Desert Storm."7 Under George Bush (41), US forces repelled Iraqi offensive forces in Kuwait in the first Gulf War, also known as Desert Storm. The eleven-month military operation was the first major show of American force in the region since World War II more than 50 years before. Today, more than 25 years since the inception of the Carter Doctrine, our present policy in the Middle East is dictated by another policy altogether: the Bush doctrine. The Bush Doctrine is a set of foreign policy guidelines first unveiled by President George W. Bush in his commencement speech to the graduating class of West Point given on June 1, 2002. The policies, taken together, outlined a broad new phase in US policy that would place greater emphasis on military pre-emption, military superiority ("strength beyond challenge"), unilateral action, and a commitment to "extending democracy, liberty, and security to all regions". The policy was formalized in a document titled The National 7 Citino, 53. 8 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. Security Strategy of the United States of America, published on September 20, 2002. The Bush Doctrine is a marked departure from the policies of deterrence and containment that generally characterized American foreign policy during the Cold War and the decade between the collapse of the Soviet Union and 9/11. The Bush Doctrine provided the policy framework for Middle Eastern policy, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, specifically.8 The effectiveness of the current (Bush) policy is best affirmed in the fact that today CENTCOM, the military manifestation of the current (Bush) doctrine, has a formal Area of Responsibility (AOR) which extends to 27 countries in the Middle East, East Africa and Central Asia: International waters included are the Red Sea, Persian or Arabian Gulf, and western portions of the Indian Ocean. The United States Central Command (CENTCOM), originally conceived of as the Rapid Deployment Forces, is a theater-level Unified Combatant Command unit of the U.S. armed forces, established in 1983 under the operational control of the U.S. Secretary of Defense. Its area of jurisdiction is in the Middle East, East Africa and Central Asia. It has been the main American presence in many military operations, including the Persian Gulf War, the United States war in Afghanistan, and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The Washington Post reported that long term plans for basing in the region include continued use of Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman and the creation of two new storage hubs in Central Asia. This 8 Hougton, 129. 9 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. policy is indeed proving the "strength beyond challenge" superiority of the armed forces of the United States.9 Because of the increasing attention that US Middle Eastern policy has received in the past few years and the heightening anti-American sentiment that is taking hold in the region as a result, it seems inevitable that at least some modifications to current policy will be made in the future. Two primary policy alternatives in the Middle East are most conceivable. A reactionary response would be to return to the ideology of the Carter Doctrine: seeking diplomatic solutions to achieve peace however also willing to use military force if outside forces intervene. Of course, the outside forces would not be Communism, as it once was, but rather rogue groups and underground networks which use terrorism to promote Jihad. This would make the United States seem more committed to peace. We would also show to the world the strength and tenacity of our resolve to confront these regional issues by not ruling out military actions if provoked. Another alternative would be an extension of the Bush doctrine. Not only to use pre-emption to extend democracy and show military superiority, but to systematically build a network of military bases in every sub-region of the Middle East. These bases would conduct regular military and reconnaissance exercises, sometime working in conjunction with “friendly” nations’ armed forces. While this would both allow 9 Washington Post, Nov. 2004. 10 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. American commanders first-strike capabilities immediately and by extension allow us to respond to any political, social or economic issue in a more timely manner, it could be seen as another expansion of American hegemony and be met with wide resistance in both the masses and their leaders. As the United States finds itself in the midst of another crisis in the Middle East, it is important to ask why there is hostility toward America in that region. Some insight can be gained by surveying official U.S. conduct in the Middle East since the end of World War II. American policymakers who presently find themselves wedged between President Bush’s stance on the Middle East and the public’s perception of the situation there is not unique to American modern history. Eisenhower’s administration too was steadfast on protecting America’s interests in the region, while being forced to deal with a public weary of war (WWII had just ended) and skeptical of the heightening situation (The Cold War brought unprecedented challenges in the latter 20th century). Acknowledged herein is a fundamental, yet deplorably overlooked, distinction between understanding and excusing: not to advocate one policy over another but rather to analyze holistically a doctrine which has helped to dictate American involvement in the Middle East for past several decades. In the aftermath of the most overt and direct U.S. attempt to manage affairs in the Middle East, the Operation for Iraqi Liberation, it is more important than ever to 11 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. understand how the United States came to be involved in the region and the disastrous consequences of that involvement. President Bush's willingness to sacrifice American lives to remove Iraqi leadership and to restore "democracy" proceeds logically from the premises and policies of past administrations: i.e. Truman’s policy of containment and Nixon’s promise to secure America’s vital interests. Indeed, there is little new in Bush's new world order, except the Soviet Union's absence. While America became the world’s only remaining superpower with the collapse of the USSR in 1991, we inherited new challenges. Our enemies now, in our War Against Terror, have neither geographical borders nor concrete ideologies. Some may argue that we can not even compare the new world order to the old; i.e. the dizzying pace of technological change has brought us challenges we have never had before; transnational threats, rise of India and China, interwoven economies, etc. Whether this new order will be more or less dangerous than the old is yet to be seen, but it is certain that it will feature an activist U.S. foreign policy without the inhibitions that were formerly imposed by superpower rivalry. 12 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. Bibliography Abrahamian, Ervand. Radical Islam: The Iranian Mojahedin (Society and culture in the modern Middle East). Boston: I.B. Tauris, 1989. Aslan, Reza. “Days of Rage.” Nation, 12/13/2004, Vol. 279 Issue 20, p15-18. Benner, David. “Carter’s Folly.” Foreign Policy Journal, Vol. 134 Issue 17, p. 3-7. Bowden, Mark. Guests of the Ayatollah: The First Battle in America's War with Militant Islam. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2006. Brzezinski, Zbigniew. Power and Principle: Memoirs of the National Security Adviser, 1977-1981. Chicago: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 1983. Carter, Jimmy. The Personal Beliefs of Jimmy Carter: Winner of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2002. Carter, Jimmy. Our Endangered Values: America's Moral Crisis. New York: US Army War College, 2006. Citino, Nathan J. “Taken Hostage: The Iran Hostage Crisis and America's First Encounter with Radical Islam.” American Historical Review, Apr2006, Vol. 111 Issue 2, p524-524. Ellis, Richard. Debating the Presidency: Conflicting Perspectives on the American Executive. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2006. Farber, David. Taken Hostage: The Iran Hostage Crisis and America’s First Encounter with Radical Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005. Genovese, Michael. The Power of the American Presidency 1789-2000. London: Oxford University Press, 2005. Harris, David. The Crisis: The President, the Prophet, and the Shah-1979 and the Coming of Militant Islam. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2004. Houghton, David. US Foreign Policy and the Iran Hostage Crisis (Cambridge Studies in International Relations). London: Cambridge University Press, 2000. James Carter Presidential Library and Museum. Atlanta, GA. Kiewe, Amos. The Modern Presidency and Crisis Rhetoric (Praeger Series in Political Communication). New York: Praeger Publishers, 1993. Pfiffner, James. The Modern Presidency. London: Thomson and Wadsworth Press, 2005. 13 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. Precht, Henry. “Lessons from Iran hostage crisis.” Christian Science Monitor, 11/2/99, Vol. 91 Issue 236, p9. Sickmann, Rodney. Iranian Hostage: A Personal Diary of 444 Days in Captivity. Houston: Crawford Press, 1982. Stein, Conrad. The Iran Hostage Crisis (Cornerstones of Freedom. Second Series). Boston: Childrens Press, 1994. Tanter, Raymond. “US Foreign Policy and the Iran Hostage Crisis.” Middle East Quarterly, Winter2006, Vol. 13 Issue 1, p12-13. Whitney, David. The American Presidents: Biographies of the Chief Executives from George Washington to George W. Bush. New York: Readers’ Digest, 2001. Wolf, Lawrence. “America Held Hostage: The Iran Hostage Crisis of 1979-1981 and U.S .-Iranian Relations.” OAH Magazine of History; May2006, Vol. 20 Issue 3, p27-30. Yergen, David. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. New York: Free Press, 1993. 14 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. Appendix A Map of the Middle East (present) 15 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. Appendix B Map of the Middle East (circa. 1915) 16 Policy Analysis Paper Darrell J. Bennett, Jr. Appendix C Map of the Middle East (circa. 1250) 17