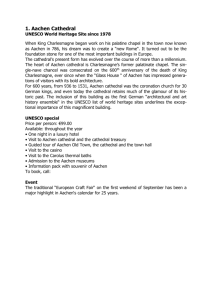

Restoring Charlemagne's chapel: historical consciousness, material

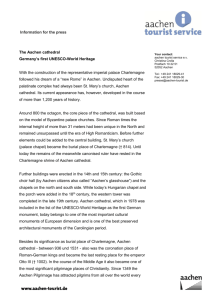

advertisement