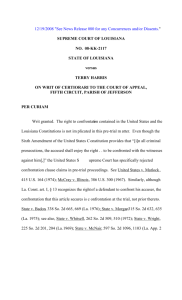

the confrontation clause and pretrial hearings

advertisement