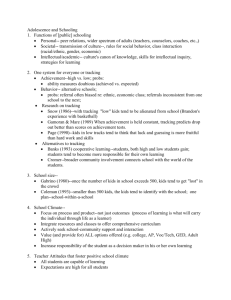

Against Schooling:Education and Social Class

advertisement