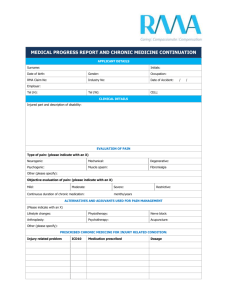

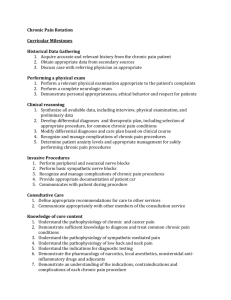

literature review: models of care for pain management

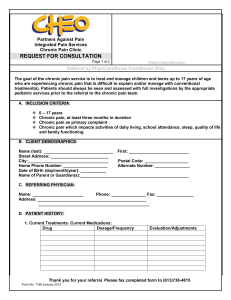

advertisement