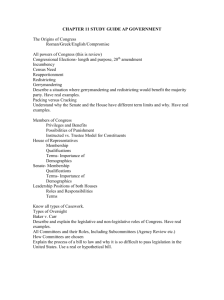

David Schultz - Rutgers Law Journal

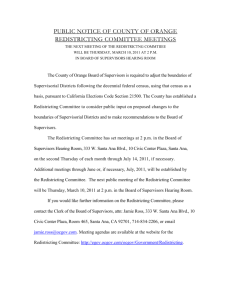

advertisement