The Federalist Era

advertisement

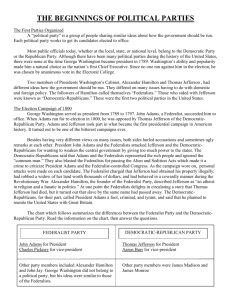

THE FEDERALIST ERA (Washington and Adams Administrations) WASHINGTON’S ADMINISTRATION (1789-1797) Election • • unanimous choice of the Electoral College inaugurated on April 30, 1789 in New York City Organizing the Government • • • as stated in Constitution, Washington created the first Cabinet: Sec. of State – Thomas Jefferson Sec. of Treasury – Alexander Hamilton Sec. of War – Henry Knox Attorney General – Edmund Randolph Judiciary Act of 1789: determined the number of Supreme Court justices (1 Chief + 5 Assoc’s) also set up 13 district courts and 3 courts of appeals Bill of Rights (ratified in 1791) first 10 Amendments to Constitution concession to Anti-federalists’ demands largely based on George Mason’s bill of rights in Virginia Hamilton’s Financial Program B ank of the U.S. (depository of federal funds and printer of national currency) E xcise Taxes (a tax on manufacture and distribution of non-essential consumer goods – e.g., whiskey) F unding at Par (pay off entire national debt – approx. $75M – with interest to show credibility) A ssumption of State Debts (remove financial burden from states, make fed. gov. the focus; increased N-S tensions) T ariffs (collect revenue to pay debt; protect American industries) Foreign Affairs • • • • • France Americans generally supported French Revolution (spirit of republicanism) U.S.-French alliance still in effect, but with monarchy, not Republic British ships continued to seize U.S. merchant ships bound for French ports Neutrality Proclamation (1793) – Washington feared the U.S. too weak to defend itself from any hostile force; Federalists supported NP, Jeffersonians enraged Citizen Genet - French minister to U.S. who ignored proclamation and tried to bypass Washington and appealing to Americans to support France (he was recalled/naturalized) Jay’s Treaty (1794) Britain agreed to evacuate posts on U.S. frontier (once again!) no stipulation about seizing American ships THE FEDERALIST ERA (Washington and Adams Administrations) • U.S. agreed to pay off Rev. War debts British agreed to pay damages for seizures of American ships Southerners irate – felt Northern interests sold them out France upset, but U.S. averted war, remained neutral Pinckney’s Treaty (1795) – fearing possible U.S. –Britain alliance, Spain: agreed to right of deposit at New Orleans for U.S. farmers accepted border of 31st parallel Domestic Affairs • Native Americans frontiersmen irate over British support of Natives’ resistance Battle of Fallen Timbers (1794) - General Anthony Wayne’s laid basis for more western settlement; many Indians abandoned allies Treaty of Greenville (1795) – Miami Confederacy yielded land in NW Territory in exchange for cash payments; British abandoned forts in Old NW • Whiskey Rebellion (1794) farmers in western PA protested by attacking revenue collectors GW federalized 15,000 state militia under Hamilton (bloodless ending) seen as power of federal govt. to “ensure domestic tranquility” many westerners decried the unwarranted use of force against “commoners” • Western Settlement Public Land Act (1796) – established procedures for selling federal lands at prices 3 new states were added: Vermont, Kentucky, Tennessee • Development of Political Parties seen by “Founding Fathers” as disloyal and against spirit of unity previous factions (e.g., federalists and antifederalists) were not political parties Hamilton-Jefferson feud evolved into the first parties Resignation • • retired after 2 terms (became precedent for next 150 years) Farewell Address (1796) included several warnings about course of the nation evils of political parties (GW was never officially a member) avoid permanent “entangling” alliances (beginning of isolationist model) victory British as claims to fair THE FEDERALIST ERA (Washington and Adams Administrations) Washington’s Farewell Address (1796) Friends and Fellow Citizens: . . . In looking forward to the moment which is intended to terminate the career of my political life, my feelings do not permit me to suspend the deep acknowledgment of that debt of gratitude which I owe to my beloved country for the many honors it has conferred upon me; still more for the steadfast confidence with which it has supported me, and for the opportunities I have thence enjoyed of manifesting my inviolable attachment by services faithful and persevering, though in usefulness unequal to my zeal. . . . Here, perhaps, I ought to stop. But a solicitude for your welfare, which cannot end but with my life, and the apprehension of danger, natural to that solicitude, urge me on an occasion like the present, to offer to your solemn contemplation and to recommend to your frequent review some sentiments which are the result of much reflection, of no inconsiderable observation, and which appear to me all important to the permanency of your felicity as a people. . . . The unity of government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so, for it is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad, of your safety, of your prosperity, of that very liberty which you so highly prize. But as it is easy to foresee that from different causes and from different quarters much pains will be taken, many artifices employed, to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth, as this is the point in your political fortress against which the batteries of internal and external enemies will be most constantly and actively (though often covertly and insidiously) directed, it is of infinite moment that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national union to your collective and individual happiness; that you should cherish a cordial, habitual, and immovable attachment to it; accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it as the palladium of your political safety and prosperity; watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned, and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our country from the rest or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts. . . . In contemplating the causes which may disturb our union it occurs as a matter of serious concern that any ground should have been furnished for characterizing parties by geographical discriminations— and Southern; Atlantic and Western— designing men may endeavor to excite a belief that there is a real difference of local interests and views. One of the expedients of party to acquire influence within particular districts is to misrepresent the opinions and aims of other districts. You cannot shield yourselves too much against the jealousies and heartburnings which spring from these misrepresentations; they tend to render alien to each other those who ought to be bound together by fraternal affection. . . . This Government, the offspring of your own choice, uninfluenced and unawed, adopted upon full investigation and mature deliberation, completely free in its principles, in the distribution of its powers, uniting security with energy, and containing within itself a provision for its own amendment, has a just claim to your confidence and your support. Respect for its authority, compliance with its laws, acquiescence in its measures, are duties enjoined by the fundamental maxims of true liberty. . . . The very idea of the power and the right of the people to establish government presupposes the duty of every individual to obey the established government. . . . Let me now take a more comprehensive view, and warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the spirit of party generally. This spirit, unfortunately, is inseparable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human mind. It exists under different shapes in all governments, more or less stifled, controlled, or repressed; but in those of the popular form it is seen in its greatest rankness and is truly their worst enemy. . . . It serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms; kindles the animosity of one part against another; foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government THE FEDERALIST ERA (Washington and Adams Administrations) itself through the channels of party passion. Thus the policy and the will of one country are subjected to the policy and will of another. There is an opinion that parties in free countries are useful checks upon the administration of government, and serve to keep alive the spirit of liberty. This within certain limits is probably true; and in governments of a monarchical cast patriotism may look with indulgence, if not with favor, upon the spirit of party. But in those of the popular character, in governments purely elective, it is a spirit not to be encouraged. From their natural tendency it is certain there will always be enough of that spirit for every salutary purpose; and there being constant danger of excess, the effort ought to be by force of public opinion to mitigate and assuage it. A fire not to be quenched, it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume. As a very important source of strength and security, cherish public credit. One method of preserving it is to use it as sparingly as possible, avoiding occasions of expense by cultivating peace, but remembering also that timely disbursements to prepare for danger frequently prevent much greater disbursements to repel it; avoiding likewise the accumulation of debt, not only by shunning occasions of expense, but by exertions in time of peace to discharge the debts which unavoidable wars have occasioned, not ungenerously throwing upon posterity the burthen which we ourselves ought to bear . . . . [B]ear in mind that toward the payment of debts there must be revenue; that to have revenue there must be taxes; that no taxes can be devised which are not more or less inconvenient and unpleasant . . . In the execution of such a plan nothing is more essential than that permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular nations and passionate attachments for others should be excluded, and that in place of them just and amicable feelings toward all should be cultivated. The nation which indulges toward another an habitual hatred or an habitual fondness is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its animosity or to its affection, either of which is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty and its interest. . . . The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is, in extending our commercial relations to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop. . . . Harmony, liberal intercourse with all nations are recommended by policy, humanity, and interest. But even our commercial policy should hold an equal and impartial hand, neither seeking nor granting exclusive favors or preferences; . . . diffusing and diversifying by gentle means the streams of commerce, but forcing nothing; . . . constantly keeping in view that it is folly in one nation to look for disinterested favors from another. . . . There can be no greater error than to expect or calculate upon real favors from nation to nation. It is an illusion which experience must cure, which a just pride ought to discard. . . . I anticipate with pleasing expectation that retreat in which I promise myself to realize without alloy the sweet enjoyment of partaking in the midst of my fellow-citizens the benign influence of good laws under a free government— ever-favorite object of my heart, and the happy reward, as I trust, of our mutual cares, labors and dangers. Geo. Washington Questions to Consider 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Briefly summarize George Washington's beliefs about political parties. What warning about foreign nations does Washington give in his farewell address? Why do you think Washington was so concerned about these two issues? Evaluate the role of political parties in today's national scene. Were Washington's concerns valid for the future of the nation? Are the concerns that Washington had about the nation's foreign affairs still applicable today? Why or why not? THE FEDERALIST ERA (Washington and Adams Administrations) ADAMS’ ADMINISTRATION (1797-1801) Election of 1796 • • ran as a Federalist defeated Thomas Jefferson (Democratic-Republican), who became Vice President Hostilities with France • • • • French protested Jay’s Treaty (considered it abandonment of Franco-American alliance) French warships seized ~300 U.S. ships XYZ Affair American delegates sent to Paris in 1797 approached by three French agents (“X, Y, and Z”) demanding a bribe to meet with Foreign Minister negotiations broke down, war hysteria swept the U.S. Undeclared (“Quasi”) War: 1798-99 Navy Dept. created, army authorized all trade with France suspended; Adams ordered all French vessels to be captured Convention of 1800 (Adams’ “finest moment”) French urged peaceful settlement (avoid pushing the U.S. towards G.B.) Convention of 1800 ended 22-year Franco-American alliance; included agreement by U.S. to pay damages averted a major war Alien and Sedition Acts (1798) • a series of laws designed to reduce Jeffersonians’ power and reduce anti-war opposition • Alien Acts raised residence requirement for U.S. citizenship from 5 years to 14 years authorized President to deport “dangerous” foreigners Federalists justified it by citing foreign interference (e.g., Citizen Genet) Democratic Republicans questioned legality/motives never enforced, but cast Federalists as supporters of excessive governmental power • Sedition Act criminalized anyone who impeded government policies of falsely criticized its leaders punishments included heavy fines and imprisonment direct violation of the 1st Amendment (you know, that pesky free speech thing!) anti-French hysteria led to widespread popular support of Sedition Act mostly Democratic-Republicans targeted for prosecution law expired in 1801 (day before Adams left office) THE FEDERALIST ERA (Washington and Adams Administrations) Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions (1798) • authored by Jefferson (V.P. at the time!) and Madison • declared Alien and Sedition Acts unconstitutional (though no court had ruled such) asserted rights of states to nullify laws passed by Congress compact theory: the federal government was created by the states, who therefore retained ultimate power aim was not to break union but preserve it by protecting civil liberties • Federalists countered that “the people” had created the union, therefore states could not nullify • no other state passed these resolution Election of 1800 • John Adams (Federalist) vs. Thomas Jefferson (Democratic-Republican) • Federalist weaknesses split over decision to go to war with France (Hamilton and others openly criticized Adams for not declaring war Alien and Sedition Acts became a liability new taxes (e.g., whiskey, new stamp tax) were unpopular debt increased as Federalists prepared for war • Jefferson defeated Adams Federalists would never again hold the office of the President • • • • • The Federalist Legacy Hamilton’s Financial Plan (BEFAT) Washington’s precedents (e.g., Cabinet, two terms) Federalists kept the U.S. out of war Contributed to growing chasm of political parties (Dem-Rep’s also) Laid basis for further westward expansion (see Greenville’s Treaty) *** Subject to Debate *** Did the Federalists preserve the gains of the Revolution for future generations or did they curtail them when their power was threatened? Conservative Federalist Party attack ad depicts Jefferson as attempting to destroy the Constitution, stopped by God and an American eagle.