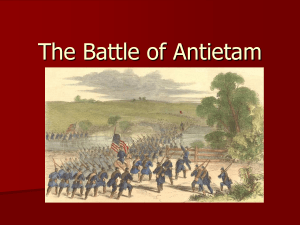

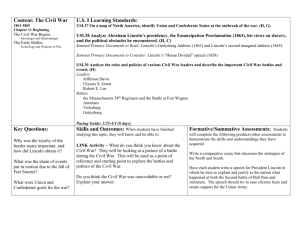

1 Battle of Antietam The bloodiest single day in American history, the

advertisement

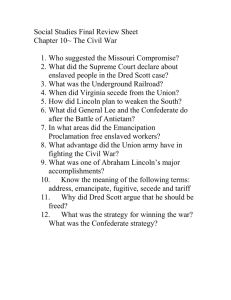

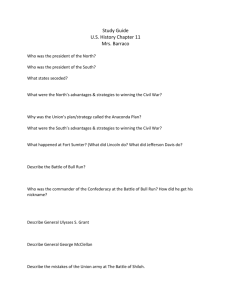

Battle of Antietam © Civil War glass negative collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, PLC-DIG-cwpb01109 The bloodiest single day in American history, the Battle of Antietam was fought near Sharpsburg, Maryland on September 17, 1862. Though the fighting ended in a draw, the Confederate retreat was seized upon as a Union victory, enabling Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. The Confederacy’s failure to invade the North also issued a severe political cost. Lacking confidence in General Robert E. Lee’s troops, Great Britain postponed its recognition of the Confederate Government, which severely hampered the Rebels’ war effort. 1 Stephen W. Sears, author of Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam states, “Of all the days on all the fields where American soldiers have fought, the most terrible by almost any measure was September 17, 1862” (Sears xi). In the summer of 1862, General Robert E. Lee’s army was making its way North through Maryland. On September 17, the Union and Confederate forces met in Sharpsburg, Maryland. The battle opened in Miller’s cornfield when Union General Joseph Hooker began firing on Stonewall Jackson’s men. Hooker recalls “every stalk in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before. It was never my fortune to witness a more bloody, dismal battlefield” (Cannan 119). Meanwhile, in the Sunken Road, Union General William H. French’s division battled with General D.H. Hill’s troops. The fighting was so gruesome that the battlefield would later be known as Bloody Lane. Southeast of Sharpsburg, General Ambrose Burnside was attempting to cross a narrow bridge over Antietam Creek while facing crossfire from a group of 400 Georgians. The attempt lasted for four hours before the Union troops crossed the bridge and drove back the Georgians. At the end of the day, nearly 23,000 soldiers had died, the most casualties of any single day in the war. Federal losses were numbered at 12,410 and Confederate losses numbered at 10,700. Captain Emory Upton of the 2nd U.S. Infantry stated, “I have heard of ‘the dead lying in heaps,’ but never saw it till this battle. Whole ranks fell together.” After the battle, Lee’s Army retreated south across the Potomac, and the Confederate’s first northern campaign was ended. One enslaved onlooker, Hillary Watson, recalled the battle first hand: “The shells soon begun flying over the house and around here, and while I was out in the yard there was one that appeared like it went between our house and the next, and busted. I could see the blue blaze flying, and I jumped as high as your head” (reprinted in Ward 96). Although the Battle of Antietam was not regarded as a victory for the Union, it instilled enough confidence in Lincoln to proceed with the unveiling of a massively important document. On September 22, 1862 Lincoln issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which said, “That on the first day of January, in the year of our lord one thousand eight hundred sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State, or any designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever, free.” Despite the fact that the battle was a draw militarily, the aftermath was a tremendous political victory for the Union. Not only was Lincoln encouraged to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, one of the single most important documents in American History, but the Confederates also suffered a substantial political loss. Because of Lee’s failure to invade the north, Great Britain decided to postpone their recognition of the Confederate Government. If Great Britain had allied with the Rebels during the war, the result may have been completely different. 2 Works Cited & Further Reading Cannan, John. The Antietam Campaign. New York: Gallery, 1990. Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003. Ward, Andrew. The Slaves’ War: The Civil War in the Words of Former Slaves. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009. 3